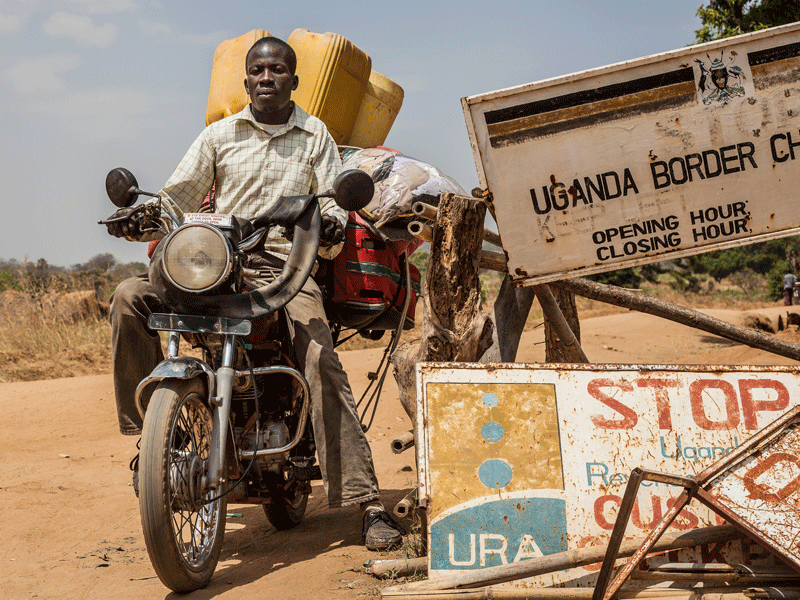

“Life has changed. We used to stay home helplessly, but now we plan. Having a business keeps you busy and brings you money,” Ojara Wilson told World Finance, reminiscing about the recent past. Ojara runs a business specialising in buying and selling silverfish in Nwoya, Uganda, backed by Village Enterprise, an NGO that supports micro-entrepreneurship in Uganda and Kenya.

Of all the parts of the world where humanitarian aid is needed, sub-Saharan Africa stands out as the most challenging

“Before the Village Enterprise training, we did not know how to run a business. But now we understand how to save money for the future, which can pay for school fees, medical care and small things in the home,” Ojara said. Through the programme, he explained, he learned how to keep records and use a bank account: “We used to keep our money here at home, but now we don’t because of Village Enterprise. Now we keep the money in the bank and only withdraw [it] when needed.”

A new development tool

Of all the parts of the world where humanitarian aid is needed, sub-Saharan Africa stands out as the most challenging. Around 51 percent of the world’s extremely poor children live in sub-Saharan Africa, according to a 2016 report by UNICEF and the World Bank (see Fig 1), with around 38 percent of adults in the region also living in extreme poverty (see Fig 2).

Village Enterprise is one of the many NGOs active in the region that focus on supporting sustainable entrepreneurship to boost growth. To fund its activities, the organisation has raised funds through a development impact bond (DIB), an innovative financial instrument that holds the promise of revolutionising international development finance. Issued in November 2017, the $5.26m bond will be repaid to its issuers only if the programme hits specific targets pertinent to consumption and net assets in the participating communities. Overall, the project is expected to support more than 12,000 households and 4,000 microenterprises in Kenya and Uganda.

DIBs involve an investing institution that is willing to offer a service provider – typically an NGO – the funds necessary to implement a project in a developing country. If pre-agreed, measurable targets are met, another donor organisation refunds the capital with a premium to the initial investor. The consortium backing the Village Enterprise DIB include the US and UK government agencies responsible for international development, an anonymous philanthropic fund, and the Global Development Incubator, a US social enterprise incubator.

As a new beast in finance, DIBs are often criticised as too arcane and time-consuming to design. This is partly true, according to Village Enterprise’s Senior Director of Institutional Partnerships, Caroline Bernadi: “Because we are paving new ground, figuring out the best structure for investment and the necessary steps to make it a reality [was] time-consuming, resource-intensive and complex.’’ Village Enterprise was responsible for raising the working capital, which created significant challenges: partway through the process, the organisation’s leadership realised that launching a new entity was needed to receive the investment. But in the end, it was worth it, said Bernadi: “It makes money more effective. By tying funding to measurable results, impact bonds reduce the risk of funding programmes that do not work.”

Results business

DIBs are the latest entry in a growing list of innovative financial instruments with a humanitarian focus. Some are replicating experiments already made in the developed world, such as the hotly debated universal basic income. GiveDirectly – an NGO funded by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar and Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz and his wife Cari Tuna – has launched an aid programme in Kenya that will offer a fixed income to 26,000 people. Other organisations borrow ideas from the financial and technology realms: Laurene Powell Jobs, Steve Jobs’ widow, runs the Emerson Collective, an organisation that uses portfolio management strategies to fund charitable causes. Another donating organisation, the Draper Richards Kaplan Foundation, was launched by prominent venture capitalists and is applying a venture funding model to philanthropy.

The Brookings Institution, a US think tank that closely follows the evolution of international development finance, identifies in a recent report the confluence of three trends that contributed to the emergence of DIBs: impact investing, results-based financing and public-private partnerships.

Impact investing brings a new approach to financial investments that seek to have a positive effect on society with financial returns

Impact investing brings a new approach to financial investments that seek to have a positive effect on society with financial returns. It can take the form of investing in green bonds, financing environmental projects such as clean energy, or social impact bonds that fund welfare, employment and education programmes. DIBs apply the same concept in countries where humanitarian intervention is more urgent, going beyond traditional payment-by-results programmes.

They can also bring more private donors into the game, according to Bernadi: “By creating an investment opportunity that includes a financial return, impact bonds could exponentially increase the pool of capital available [to fund] international development projects around the world, [which] today depend on a limited pool of international development aid and donations.”

Focusing on measurable results is a response to the pressure NGOs and government agencies feel from taxpayers, who increasingly see foreign aid as a resource that could be better spent domestically. An overwhelming 84 percent of respondents in a 2018 poll by OnePoll supported the idea of diverting big chunks of the UK foreign aid budget to the NHS. The picture is similar on the other side of the Atlantic, where polls show that support for foreign aid is historically low. Private donors are also becoming more circumspect, demanding to see specific results whereas previously they were content with mere promises.

Avnish Gungadurdoss, co-founder of Instiglio, an international development consultancy specialising in results-based finance, said: “Usually with traditional development projects, people say what results they will achieve, [but] they are not really backed by any evidence… Nothing happens if you don’t achieve the results or you overachieve, so it’s an easy conversation to have.’’ Striving to convince taxpayers and large private donors that their money is not wasted, NGOs are putting more emphasis on matching payments to measurable outcomes.

Another reason international development organisations are changing their ways is the need to scale up interventions to meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which envisage the elimination of poverty and hunger by 2030. The UN estimates that annual investments of $3.3trn to $4.5trn will be required to meet these targets.

DIBs can be a cog in the giant funding machine needed to meet the SDGs, according to Emily Gustafsson-Wright, a fellow at the Centre for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution and an expert on international development: “DIBs have the potential to focus attention on the targets associated with the achievement of the SDGs, and to engage private capital to bridge the financing gap to achieving them.”

Education, education, education

If there is one area where DIBs can bring change, it is education, said Vikram Solanki, Senior District Manager at Educate Girls, an NGO funding an education programme in the Indian state of Rajasthan through a DIB: “A results-driven approach forces one to repeatedly figure out what isn’t working and then think of solutions. So the DIB programme has made all of us thinkers and problem-solvers.” Launched in 2015, the programme aims to increase the number of out-of-school girls enrolled in primary schools, as well as the performance of all students in a range of subjects including English, Hindi and mathematics, within three years.

2030

The year by which the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals aim to eliminate poverty

$3.3-$4.5trn

Yearly amount the UN estimates will be needed to meet its Sustainable Development Goals targets

51%

Percentage of world’s extremely poor children that live in sub-Saharan Africa

$5.26m

Value of the Village Enterprise development impact bond issued in November 2017

12,000+

Number of households the Village Enterprise development impact bond will support in Kenya and Uganda

4,000

Number of microenterprises the Village Enterprise development impact bond will support in Kenya and Uganda

By using rigorous data studies, analysts and teaching staff can identify gaps and tailor the programme accordingly. Prompted by the failure to hit targets at the end of the second year, teachers divided the classroom according to learning ‘levels’ of students rather than age, while breaking down the curriculum to address the specific needs of individual children. Results released in July showed that learning and enrolment targets were met, with an impressive improvement in the performance of those girls who were hardest to reach. Enrolment was increased through a similar approach, Solanki said: “We realised that we needed to reach out to those students who were frequently missing from the classroom; our field staff started conducting home-based teaching. The DIB programme made us all truly focus on ‘the last child’.”

Thanks to the programme’s unique structure, the staff were free to make adjustments as they saw fit, according to Solanki: “The person working on the ground is the best person to suggest what the real problem is and how it should be solved. It is this flexibility that led to a host of creative classroom solutions.”

A significant problem facing NGOs involved in DIBs is the lack of quality data available in developing countries. Educate Girls carried out a door-to-door survey to create a list of out-of-school girls in 34,000 households, identifying 837 out-of-school girls and aiming to get four out of five back to school. However, the organisation was forced to renegotiate the programme’s targets when it found that government data on school population was inflated: “All this meant that in year one, we were only able to deliver seven of the planned 12 weeks of curriculum in the classroom and we had much less time to build relations with the community,” said Alison Bukhari, UK Director at Educate Girls.

Critics allege that collecting the data makes a programme more costly, thus defeating the very purpose of DIBs. But the problem justifies the emergence of DIBs rather than questioning their usefulness, said Grethe Petersen, Director of Strategic Engagement and Communications at the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF): “The lack of data in many parts of the developing world is a reason to favour the DIB approach, since it forces the programme to collect rigorous, independent, and useful information.”

Others believe that creative thinking is all it takes to tackle the problem. Kate Sturla, Associate Director at IDinsight, an organisation involved in the programme as an independent evaluator, told World Finance: “Thoughtful decisions about when to rely on existing data and when it’s essential to collect information directly can mitigate data issues. For example, estimating changes in learning levels correctly was a critical part of the Educate Girls DIB, so IDinsight hired and trained surveyors to administer short assessments directly to students rather than relying on government-administered exams.”

UBS Optimus Foundation, a philanthropic branch of the Swiss bank, provided the initial capital for the programme, while CIFF, which is a UK charity, will pay back the investor with a return of 15 percent if the goals are achieved. As with the Village Enterprise bond, the launch of the programme was challenging. “Formalising a DIB contract is tricky. Agreeing key outcomes between investors and implementers can be a long process,” Petersen said. For Instiglio, which provided technical assistance to the programme, this is a form of ‘good complexity’. Gungadurdoss said: “It’s the stuff that we don’t do enough in international development, and end up spending money on things that don’t work.”

For philanthropically minded investors, DIBs are a boon, said Maya Ziswiler, Head of Innovative Finance at the UBS Optimus Foundation: “Investors are attracted by the unique opportunity to receive both social and financial returns. Their financial return is directly linked to outcomes achieved, and investors don’t have to make [compromises] between impact and financial return.” But patience is needed to see results, she noted: “Investors will have to remain cognisant of the fact that, given the nature of the DIBs and the likely need for implementation partners to innovate to meet efficiency targets, it may take time for programmatic changes to show results.”

A private-public partnership

Most stakeholders involved in this new investment instrument agree that cooperation between public and private institutions is necessary for DIBs to succeed. For governments, this is an unprecedented opportunity to transfer the risk of getting it wrong to private investors, according to Bernadi: “The vision for the scale-up for DIBs is to involve governments as outcome funders. This would eliminate the risk of governments paying for unsuccessful programs and increase the effectiveness and impact of their social protection initiatives.”

The push for results-oriented finance is putting pressure on NGOs to do more with less, forcing them to employ management methods borrowed from the corporate world

Private donors bring their competitive ethos and results-focused doggedness to international aid. “Private sector rigour and accountability mechanisms may make investors better placed to manage risk around delivery and implementation,” said Ziswiler. Teething problems facing the nascent market include a higher risk rate that puts off many investors. These should be compensated for risk-taking, according to Ziswiler: “Risk transfer is not free. Investors must be compensated for the risk of losing money. The perceived level of risk transfer, and the required level of financial returns, will also be greater the more a risk is believed by investors to be outside of their control.”

The extent of government involvement is another point of contention: some think that governments should always be at the receiving end of these programmes. “DIBs should only be used for demonstrating the outcomes-based contracting concept to national or state governments,” said Bukhari. “Impact bonds should be aligned with government priorities and should be working towards universally agreed targets, such as the SDGs.” However, in many cases, the most significant problem facing DIB programmes are linked to governments and their sluggish ways. Legislation in many cases is prohibitive to the participation of government agencies as outcome donors, while various bureaucratic hurdles also arise. As one stakeholder interviewed by the Brookings Institution for its DIB report said: “The main challenges came when most of the people who worked on the impact bond in the beginning started moving to other departments or leaving the government.”

Setting the standard

As the DIB market is growing, questions are being raised over the need to establish universal standards on their structure and purpose. An officer from a public donor involved in a DIB told World Finance that the evaluation of the programme will encompass a study of the role standards could play in reducing the cost of DIBs. Standards, said the officer, could focus on the potential outcomes of DIB programmes as well as the types of metrics and evaluation methods that could be used. Varying definitions of what a DIB is, as well as constant innovation in the field with the emergence of new types of bonds, make standardisation a difficult task. Universal rules would help create scale, Ziswiler said: “The next step if we are to attract more mainstream investors is transition to scale, and standardisation is a key prerequisite to achieve that.” Standards will also reduce complexity and costs, according to Bukhari: “The sooner there is some level of standardisation around the contracting and some of the required elements of the structuring and negotiations, the sooner the costs will come down and they will hopefully become more useful and value for money.”

A cultural shift

The advent of DIBs marks a significant cultural shift for NGOs. Results-focused programmes require rigorous evaluation, which is a challenge for organisations lacking relevant staff and procedures. In most cases, an independent evaluator is brought in to help. Bukhari said: “It took time to fully explain the DIB concept to the whole team and align them around the new way of working. We had to hire people with different skills, as well as train and give regular ongoing professional development to bring the teams up to speed, particularly in terms of the data analysis.”

The push for results-oriented finance is putting pressure on NGOs to do more with less, forcing them to employ management methods borrowed from the corporate world, such as ‘performance management’, which encompasses rigorous evaluation and specific targets to be met by each employee. Gungadurdoss from Instiglio, which is a pioneer of performance management in international development, said: ‘’The beauty of [DIBs] is that they create an environment where organisations are focused on learning how to manage performance and achieve better results.’’

If critics lament the increasing ‘financialisation’ of international development, others hail the efficiency this new ethos brings. Gustafsson-Wright said: “Impact bonds have the potential to bring in private sector discipline from investors to service delivery organisations.” She added, however, that setting financial incentives can be counterproductive: “One concern with outcomes-based financing is that tying payment to certain results may lead to providers ignoring other important outcomes, or to focusing on one metric, rather than providing more

holistic services.”

For the time being, these concerns are of little importance for the tens of thousands of people in the developing world who benefit from DIBs and the programmes they fund. For Ojara, passing on the knowledge he has acquired to his peers is the main priority: “I use the lessons learned with Village Enterprise to help people with their own businesses. The programme empowered me to serve the community.”