Impressive though Chinese GDP figures are, few analysts trust them. This problem came to a head at the beginning of 2017, when a top official in the northeastern province of Liaoning came clean about the extent of fabrication going on behind the GDP figures for his district. The province, which has a population around the size of Spain, had been declaring growth figures that were around 20 percent higher than they were in reality. The provincial governor described it as “large-scale financial deception” that “involved many people”. He further disclosed that the falsification dated back to 2011, though even this is uncertain as many speculate that it went even further back. The revelation was received as a revealing insight into the credibility – or lack there-of – surrounding Chinese growth figures.

This is not the first time that cynicism regarding China’s official figures has come to the fore. It was back in 1995 when Zhang Sai, then the head of China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), pronounced that the “phenomenon of false and deceptive reporting has spread in some localities and some units”. It soon became commonplace for the Chinese press to run sensationalised stories calling out data falsification, which often came accompanied with the slogan ‘jiabao fukuafeng’, meaning the ‘wind of falsification and embellishment’. This eventually inspired a heavy clampdown led by the NBS, which posted investigative teams to provinces and central departments in a bid to stamp out the practice.

A number of analysts have created their own Li-inspired growth proxies in the hopes of revealing the true rate of Chinese growth

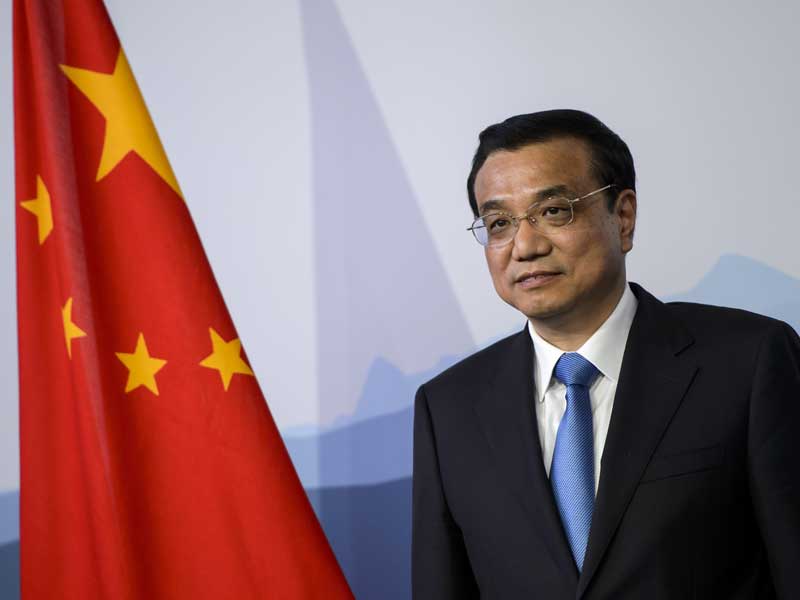

But the suspicion was not over. A 2010 Wikileaks release uncovered what is now a notorious conversation that transpired in 2007 between the US Ambassador to China and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, who at the time was a provincial governor in Liaoning. Li was quoted as saying that the growth figures in his province were “man-made”, “unreliable” and should be “for reference only”. He explained that he instead relied on three alternative measures to take the temperature of the economy: electricity consumption, rail cargo volume and the amount of loans being distributed.

Economical with the truth

Enthused by these comments, a number of analysts have created their own Li-inspired growth proxies in the hopes of revealing the true rate of Chinese growth. The Economist was the first to do so, kicking off the ‘Li Keqiang index’ in 2010, which combined the premier’s three metrics into a single index.

These indices have gradually become more refined, with analysts exploring other metrics that are likely to reflect growth. These may include floor space under construction, tonnes of cement used or even litres of beer consumed. One of the more well-known of these indices is the China Activity Proxy (CAP), which was fashioned at the independent research firm, Capital Economics. It is based on a set of five indicators, including the volume of freight being shipped on China’s roads, railways, inland waterways and by air, as well as the area of floor space currently under construction. “The indicators are relatively low profile, so they should be subject to fewer questions about data manipulation,” said Chang Liu, a China specialist at Capital Economics.

One thing that becomes clear when looking at the various iterations of the Li Keqiang index is that in comparison, the official growth statistics look suspiciously smooth: while the headline growth figures tend to come out consistently on or near target, the CAP shoots around in a far more volatile manner (see Fig 1). The conclusion to be drawn from this mismatch, which is broadly acknowledged among analysts, is that authorities have found a way to tweak the books to give the illusion of lower volatility.

The most talked-about difference, though, is that the Li-inspired figures tend to come in noticeably lower than official figures, implying that China is actually exaggerating its growth. Illustratively, the CAP has generally hovered below the level of the official figures, while the past few years have even greater divergences. “It is notable that, after moving together for nearly a decade, the two lines started to diverge in 2012,” said Liu. In fact, by the end of 2015, the CAP had dipped below four percent, implying a dramatic slowdown in growth, while official growth figures sailed through cleanly at 6.8 percent. Suspiciously, this divergence coincided with the first time China’s GDP was at risk of falling below the official growth target. The conclusion seems clear: central powers were intervening to iron out the fall in growth. Indeed, it looks like they were exaggerating growth by somewhere in the region of two percentage points.

That being said, there are several objections against taking economic measures, like the CAP, at face value. Firstly, there are questions surrounding the best way to weight each of its constituent parts. Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly, the Li Keqiang index and its copycats all hold a particularly strong focus on the industrial side of the economy, owing to their heavy emphasis on metrics, like cargo volume. This is a problem when trying to gauge growth in an economy that is in the process of transitioning away from heavy industry towards a more services-based economy. The index ends up being a better gauge of the strength of the industrial sector than growth more broadly. The further the economy shifts towards services, the more flawed Li-inspired indices will become.

Some researchers believe that a more sensible approach to detecting any data falsification is to look into satellite images and use nighttime light as a proxy for economic growth. It is well established that growth correlates with the quantity of light emitted at night, and with the right number-crunching, this can be used to assess whether official statistics are being manipulated. Embarking on this approach, researchers led by Hunter Clark from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York recently devised a deep dive into nighttime satellite images of China. Their findings throw new light onto the matter: while wary of technical limitations, they conclude that assertions of data falsification may have been exaggerated.

Inflation matters

In an effort to hone in on any foul play, most analysts point towards the inflation metric known as the GDP deflator, which is used to translate nominal growth into real growth. This oft-overlooked measure is a pivotal moving part in the growth equation because when inflation is understated, it creates the illusion of faster growth. In fact, it does this to the extent that when the deflator is understated, growth will be exaggerated by the same amount. As a result, discreet decisions surrounding the GDP deflator can wind up making a substantial difference to headline growth figure.

One thing that becomes clear when looking at the various iterations of the Li Keqiang index is that in comparison, official growth statistics look suspiciously smooth

While China publishes both nominal and GDP growth, decisions regarding the deflator go on behind closed doors so that while analysts can access the figures for themselves, they can only speculate as to where they came from. The researchers at Capital Economics dug into this quandary and found that an unlikely sequence in the deflator measure is likely to be warping the final GDP figures. Their line of reasoning is that the Chinese deflator measure does not account for import price changes in the usual way, leading to inflation being understated.

This is not necessarily an intentional manipulation by the Chinese, as it could easily reflect accounting difficulties inherent to transitioning economies. But according to those at Capital Economics, it could well have pushed the growth rate up by one or two percentage points in 2015.

Cook the books

Another well-known problem with Chinese official statistics is the fact that the career trajectories of local officials have long been linked to the economic performance of their principality. Officials that preside over high rates of growth and investment are awarded with promotion and recognition. From the point of view of a local statistician, any request to tweak results would be difficult to disobey, given that they would be coming from a direct superior. “Since the local statistics office is part of the local government, the local government leader can easily exert pressure on the local statistics office to mis-report,” said Carsten Holz, Professor of Social Science at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. It is notable that local officials might also have incentives to underreport; for instance, a poorer county may underestimate growth figures out of fear of losing subsidies.

While this opens up plenty of scope for misconduct, it doesn’t necessarily follow that the Chinese headline growth rate will be biased. Contrary to what you would expect, the national growth rate is not calculated by finding the sum of all provincial growth. Instead, the NBS compiles national growth figures with the help of its own survey teams, which don’t have any clear incentive to cook the books. In fact, the official growth rate that it comes up with is consistently far lower than the sum of provincial growth, and the discrepancy between the two is not insignificant: in 2016, it came to CNY 2.76trn ($401bn), according to Reuters’ calculations, which is greater than the GDP of Thailand.

Another problem with Chinese official statistics is the fact that the career trajectories of officials have long been linked to the economic performance of their principality

This is not to say that the national numbers are entirely untainted by local manipulations. The NBS has its own survey teams in approximately one third of all municipalities and counties, but also collaborates with local teams. With this data, it publishes an overall rate for national GDP, but falls short of publishing its own provincial estimates that would reveal discrepancies at the regional level. As Holz explained: “The NBS, in compiling GDP statistics, mostly relies on data that it collects itself, but to some extent also uses data that is collected by lower-level statistics offices and the NBS then makes adjustments to these data. How such adjustments are made, we don’t know.”

Truth be told

The Liaoning scandal, however, has landed pressure on Beijing to generate more credible GDP results. Against this backdrop, the NBS recently announced a crackdown on GDP data collection. In an interview, the deputy leader of the NBS explained that, from 2019, his own office will start to publish regional as well as national GDP figures.

$394bn

China’s official GDP 1990

$1.21trn

China’s official GDP 2000

$11.2trn

China’s official GDP 2016

As of yet, details of the change are unclear. “The provinces may continue to publish their own data, unless the NBS ends up with enough power to suppress their authority to publish their own data,” said Holz. But even if provinces continue to publish data, the NBS’ numbers will draw attention to those provinces where regional-level statistics are exaggerated. This would not eliminate the incentive for local officials to try and push up growth figures for their region, but it would make it more difficult for them to do so. Asked whether the change would make numbers more credible, Holz noted: “As long as the evaluation of local government cadres includes economic growth criteria, data coming out of local statistics offices will continue to be falsified.”

World Finance spoke to Song Houze from the Paulson Institute, who recently spent some time examining GDP manipulation in Liaoning. He felt that the upcoming reform misses the fundamental problem, and instead argued that inaccuracies are affecting the NBS itself. He explained: “All Chinese industrial firms above a certain scale are required to report their financials directly to [the NBS], and this is the primary source based on which Chinese industrial statistics are computed. But in Liaoning, many firms that are below this threshold have exaggerated their revenue to be qualified for inclusion. As a result, the data of Liaoning’s industrial sector has been exaggerated.”

An example is that in 2015, 12,304 firms exceeded this threshold, but after the 2016 data revision, that number had dropped to 8,025. Houze explained: “Since even the data directly collected by the central authority can be manipulated, I am not sure whether this recent policy can fundamentally fix the problem of data inaccuracy.”

Reality 2.0

The perception is that Beijing’s drive for credibility isn’t entirely convincing. Problems remain in terms of the transparency of the techniques used by national statisticians to convert local figures to national figures, and to generate the all-important deflator figure. Meanwhile, the suspicious smoothness of GDP remains revealing. In the end, the crackdown will have little impact if the real problem lies with the NBS itself. If manipulation is going on at a national level – through the deflator or other means – there is little to suggest this will stop.

The answer must centre around the decisions being made behind closed doors at the NBS. If we concede that Beijing is perfectly able to shift around growth rates at will, the question is why and when they would exploit this. To some extent, the debate will come down to how much trust to put into China’s national statistical body. Holz’s stance is that the NBS has “little or no incentive to falsify data, and every incentive, as a professional body and as part of the central government, to report data that accurately reflect the underlying economic activity”.

The truth is that there is inevitably some room for manoeuvre when it comes to calculating GDP

Yet it seems there is certainly some incentive to exploit this wiggle room. For one, the propaganda impact of hitting targets head on, time and time again, could be of value to politicians. Holz’s own analysis has found that China’s official growth figures are likely to be a round number without a decimal, implying that authorities have occasionally been tempted to shift around their sums to achieve a neat target rate.

In addition, from the point of view of Chinese politicians, it may be tempting to clandestinely generate some added clout on the international stage by releasing consistently impressive growth figures. However, the opposite incentive might also be proposed – for instance, with the US stoking tensions in relation to China’s export strategy, it may be helpful to understate growth.

It is easy to argue that secrecy is a clear indicator that manipulation is taking place, but the truth may be more equivocal. Holz said he suspects that adjustments are made honestly, but that even with the intention of deriving accurate values, there is simply “no precise way of doing so”. He also dug into the issue surrounding the deflator and found that plausible alternatives imply growth has generally been overestimated by around one percent. But, on the other hand, he said other equally plausible measures indicate that growth had in fact been underestimated. The main issue is that there are inherent difficulties in measuring inflation in an economy with rapidly changing product characteristics and product variety.

Truth and lies

The truth is that there is inevitably some room for manoeuvre when it comes to calculating GDP. It is often the case that different numbers might simultaneously be justified, or that legitimate tweaks are made. Seemingly trivial – but ultimately influential – judgements underpin all GDP figures.

Three years ago, the GDP of Nigeria was revised upwards by 89 percent overnight when statisticians changed the weightings allocated to different parts of the economy. Back in 2014, Italy managed to escape a recession when its GDP accounting was expanded to include its black economy of prostitution and drugs. What’s more, in the US, the Boskin Commission of 1996 prompted a revision that altered real growth rates instantaneously.

At times, these revisions are legitimate, while others are politically motivated and manipulative. Indeed, according to Walter J. Williams, a specialist in government economic reporting: “President Lyndon Johnson would review the GNP reports before their release and if he did not like it, he would keep sending the GNP estimates back to the Commerce Department until they got the numbers ‘correct’.”

Ultimately, Premier Li Keqiang’s critique of ‘man-made’ GDP has a lot of logic to it.