The mean streets of Detroit have become synonymous with dereliction, bankruptcy and abandonment; empty houses, litter-lined streets and hopeless residents. That impression existed in the 80s, when Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop was released, in which exemplary police officer Alex J Murphy is brutally gunned down in the line of duty in the deserted streets of crime-ridden downtown. But Murphy is soon reborn as RoboCop, and emerges as Detroit’s salvation; clad in metal and with guns a-blazing, he becomes the hero the city needs. Now, almost three decades later, Detroit needs a new saviour – an accountant.

The plot of Verhoeven’s film quickly descends into a brutal social commentary on gentrification, greed, privatisation and corporate capitalism; a tongue-in-cheek sci-fi classic that uses ultra-violence to mask its satire of the declining American dream. However, in the 20-odd years since its release, RoboCop has become something like a premonitory dream sequence to the events that would unfold in real Detroit in the late 1990s and 2000s. But in real life the enemy is not a robotics corporation, but the faceless threat of economic misadministration and urban decay.

Glory days

The Great Lakes region of the US was the industrial heartland of the country at the beginning of the 20th century: Chicago was renowned for its meatpacking plants, Cleveland and Pittsburgh housed steel mills, and Detroit was ‘the motor city’. The semi-glamorous capital of America’s industrial heartland, it was the home of the Cadillac and numerous other now-defunct car manufacturers. “It was the Silicon Valley of America,” Kevin Boyle, a history professor at Northwestern University who has written extensively about the city, told the local Star Tribune. “It was home to the most innovative, cutting-edge, dominant industry in the world. The money there at that point was just staggering.”

The rise of the auto industry utterly transformed Detroit, attracting over a million new migrants to the city

Detroit first experienced affluence and prosperity during the First World War, when its factories helped propel the Allies to victory. In the 1920s, it quickly grew its industry into a global motoring-manufacturing powerhouse. In the 1950s, the city was thriving, its 1.85 million inhabitants happily employed in solid blue-collared jobs. “Detroit rose and fell with the automobile industry,” writes Thoman Sugrue, the David Boies Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania. “Before the invention of the motorised, self-propelled auto car, Detroit was a second-tier industrial city with a diverse, largely regional manufacturing base. [Then] the auto industry took off.

“By the onset of the Great Depression, car manufacturing completely dwarfed financial concerns in Detroit. Many more of the city’s companies were somehow related to the auto industry, from machine tool manufacturers to auto supply companies to parts suppliers. The rise of the auto industry utterly transformed Detroit, attracting over a million new migrants to the city and, both through its demographic and its technological impact, reshaping the cityscape in enduring ways.”

By the late 1950s the city was one of the most affluent counties in the US, mostly due to auto-industry derived wealth. However, most of the power was concentrated in the hands of General Motors, Ford and Chrysler, which had grown so big they had put smaller firms out of business. At the same time, Detroit was establishing itself as the epicentre of a burgeoning labour movement, and Ford in particular was concerned about the implications this would have on his staff, who were “among the industry’s most well-organised, racially and ethnically diverse, and militant”.

Eventually, the Big Three manufacturers, led by Ford, started moving their factories into the suburbs, and that was the beginning of the end for Detroit’s industry. “What happened in Detroit is not particularly distinct,” explains Boyle. “Most Midwest cities had white flight and segregation. But Detroit had it more intensely. Most cities had deindustrialisation. Detroit had it more intensely.”

Slippery slope

By the 1970s, the city that had been the motor of the industrial heartland had seen a sharp decline in population (see table over leaf), as blue-collar workers moved away after the factories. Large swathes of the city lay abandoned as the city failed to attract replacement businesses. Detroit had also been the scene of race riots and labour movement riots over the previous decade – after the notorious riots of 1967, thousands of small businesses closed permanently or relocated. Though 43 people were killed and scores more injured, Coleman Young, Detroit’s first black mayor, wrote “the heaviest casualty… was the city”.

Detroit’s losses went a hell of a lot deeper than the immediate toll of lives and buildings. The riot put Detroit on the fast track to economic desolation, mugging the city and making off with incalculable value in jobs, earnings taxes, corporate taxes, retail dollars, sales taxes, mortgages, interest, property taxes, development dollars, investment dollars, tourism dollars and plain damn money.

“The money was carried out in the pockets of the businesses and the white people who fled as fast as they could,” wrote Young. “The white exodus from Detroit had been prodigiously steady prior to the riot, totalling 22,000 in 1966, but afterwards it was frantic.” As the population declined and the industry fled the city, tax revenues were down and unemployment was up (see table over leaf). Today, a little over 700,000 people live in the city, 23.1 percent of whom are unemployed – the highest rate among the 50 largest cities in the country, according to the US Department of Labour’s Bureau of Labour Statistics. Detroit is plagued by sprawling urban blight, having lost over half its population in three decades; levels of urban decay are unrivalled anywhere else in the US. In some parts of the city, more than half of all residential lots are abandoned.

The city’s problems were compounded by a succession of incompetent and corrupt leaders. In 2010, Kwame Kilpatrick, mayor from 2002 to 2008, was convicted on felony charges of counts of fraud, mail fraud, wire fraud, racketeering, perjury and obstructing the course of justice. He has been linked to a number of scandals, from funnelling state money for his wife to murder. Hardly the leader a beleaguered city such as Detroit needed – and he was not the only corrupt official by a long shot.

“I think it (the fiscal disaster) was inevitable because the politicians in Detroit were always knocking the can forward, not confronting the issues, buying off public employees by increasing their pensions,” said Daniel Okrent, a Detroit native journalist, to the Star Tribune. “They were always kind of confronting the impending crisis by trying to make it the next guy’s crisis.”

As expected, urban decay and corruption bring a host of other socio-economic problems, from high levels of crime and marginalisation, to poor health and education indexes. Detroit is like a ghost town today. Economically, the city is utterly unviable. There is no industry and large swathes of the population pay little or no tax. Since the economic crisis faced by the US in 2008, things have gotten even bleaker, as homes were reposed and left to rot.

The number of retirees outstrips that of active employees by a ratio of two to one, a figure nothing short of catastrophic for a city such as Detroit. The city has become the desolate dystopia Verhoeven envisioned in RoboCop almost three decades before. But Detroit is not a city without hope. The Michigan State Government, led by Rick Snyder, tried assuming control of the city’s finances in 2013 in order to lift it out of squalor, and before the city was declared bankrupt in May, an emergency financial manager was put in place to restore the city to financial health.

Parachuting in a hero

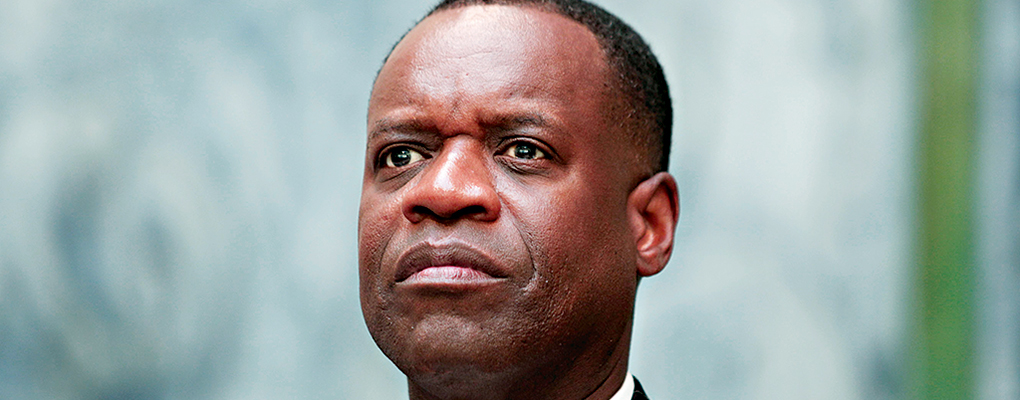

When Snyder appointed Kevyn Orr in 2013, he seemed like the fiduciary RoboCop Detroit needed. He did not appear daunted by the gargantuan task ahead of him. In his first report in charge of the city’s finances he wrote Detroit “is clearly insolvent. The City of Detroit continues to incur expenditures in excess of revenues, despite cost reductions and proceeds from long-term debt issuances. In other words, Detroit spends more than it takes in – it is clearly insolvent on a cash flow basis.”

By that point, the city had a negative cash position of $162m, with expenditure exceeding revenue by over $100m a year between 2008 and 2012. Additionally, the city had accrued around $18bn in debt, which Orr had to address. “The 45-day report I have submitted is a sobering wake-up call about the dire financial straits the city of Detroit faces. No one should underestimate the severity of the financial crisis. The path Detroit has followed for more than 40 years is unsustainable, and only a complete restructuring of the city’s finances and operations will allow Detroit to regain its footing and return to a path of prosperity.”

Fast-forward two years and Orr’s emergency bankruptcy exit plan has just been approved, and a deal reached between the emergency manager and the elected city council. It is the first step into recovery after the city became the largest in the US to file for Chapter 9 bankruptcy, in late 2013. But the road to salvation has not been smooth for Orr, and it promises to remain rocky as the city moves to implement his recovery plan.

In the 18 months since his appointment, Orr has faced relentless opposition from the city of Detroit. When Snyder put Orr in control as emergency manager in 2013 he, in effect, gave this unelected official the power to overrule the city government. As Detroit was placed under state control as part of the Section 9 proceedings, Orr was given the power to override officials, rewrite labour contracts, negotiate deals, privatise services, open new contracts and sell assets. It is a difficult situation.

On the one hand Detroit has been burdened with decades of poor and at times corrupt management; on the other, Orr is not an elected official, and there are questions about how constitutional his appointment and subsequent actions are. Even municipal judges suggested the motion to file for Chapter 9 was unconstitutional.

“I think it’s very difficult right now to ask directly for support,” Detroit Mayor David Bing told the press at the time of the bankruptcy filing. “We’re not the only city that’s going to struggle through what we’re going through. We may be one of the first. We are the largest, but we will absolutely not be the last. And so we have got to set a benchmark in terms of how to fix our cities and come back from this tragedy.”

And so, amid opposition from city councillors, Orr devised a plan to rehabilitate Detroit’s finances. The city is still facing strong headwinds. Property tax revenues have slumped 19.7 percent in the last five years, as property values have declined. Income tax revenues have declined by $91m since 2002 – close to 30 percent – and by $44m since 2008 (approximately 15 percent) due to high unemployment rates. In the meantime the comparative tax burden per capita has gone through the roof, making it the highest in Michigan.

All these factors, compounded by continuing budget deficits and mounting debt, mean the city is in a liquidity crisis and can no longer afford to support itself. In April 2013, 40 percent of streetlights were not functioning. Detroit’s problems are not easily solved because of the decades of lack of investment in infrastructure; it continues to accrue tremendous costs associated with abandoned buildings, and almost all public assets (including fire apparatus, and police apparatus and facilities) need upgrading or replacing altogether. Essentially, nothing in the city is functioning to standard.

Orr’s plans revolve around the need to “provide incentives [and eliminate disincentives] for businesses and residents to locate and/or remain in the city”, and “maximising recoveries for creditors”. This will involve pension reforms, employment reforms, attracting outside investment to physically rebuild the derelict city in order to maximise the collection of taxes and fees, and offloading city assets that can generate capital. It is an uphill struggle.

Road to recovery

In the months since Orr released his report and outlined his strategy, he has been trapped doing vicious battle with the city council for the chance to implement his plans. At one point it looked as if he would be ousted, until, finally, at the end of September, a hard-fought deal was reached. The deal between Orr, Duggan and other councillors, means Detroit will remain under emergency management as Orr steers it through the final stages of Chapter 9. However, some of his overriding powers have been stripped, and he will no longer have final say over city contracts.

The deal is being lauded as a victory for councillors. Council President Brenda Jones has been adamant to stress power has been returned to the hands of elected – and accountable – officials, but added Orr still has a vital role to play in the city’s recovery. “We do not want to stand in the way of the bankruptcy proceeding,” Jones said. “None of us are bankruptcy lawyers.”

Michigan Governor Rick Snyder, who appointed Orr as emergency manager in the first place, issued a statement praising the deal and the decision to phase out Orr’s role as emergency caretaker. “Detroit continues to move forward. Today’s transition of responsibilities is a reflection of the continuing cooperation between the state and its largest city,” the statement read. “Leaders are working together for the best interests of Detroit and all of Michigan. Emergency manager Kevyn Orr’s expertise and counsel to the mayor and city council are vital in guiding the city toward a successful conclusion of the bankruptcy process.”

However, despite conflicts, Orr’s role in putting Detroit on the road to recovery cannot be denied. It may have been an unpopular move, but filing for Chapter 9 Bankruptcy was the drastic initiative that had been lacking from local leaders who had allowed the precarious situation in Detroit to slide. The city is still fundamentally in ruins as reconstruction and regeneration have not begun, and it will take a Homeric effort to propel recovery forwards. But Detroit has an aim and a clear direction now. No reanimated fighting robot is necessary.