Why central banks are turning to gold

Gold’s surge to $4,000 an ounce marks more than a price record – it signals a retreat from the US dollar and a new era of risk aversion as nations seek political and financial insulation

Gold prices continue to break new price records. During the second week of October 2025, gold had surged to $4,000 a troy ounce, and the Financial Times reports that prices have doubled in less than two years because central banks are stockpiling bullion and investors are pouring into gold funds. This is despite central banks’ investments in gold slowing in July 2025.

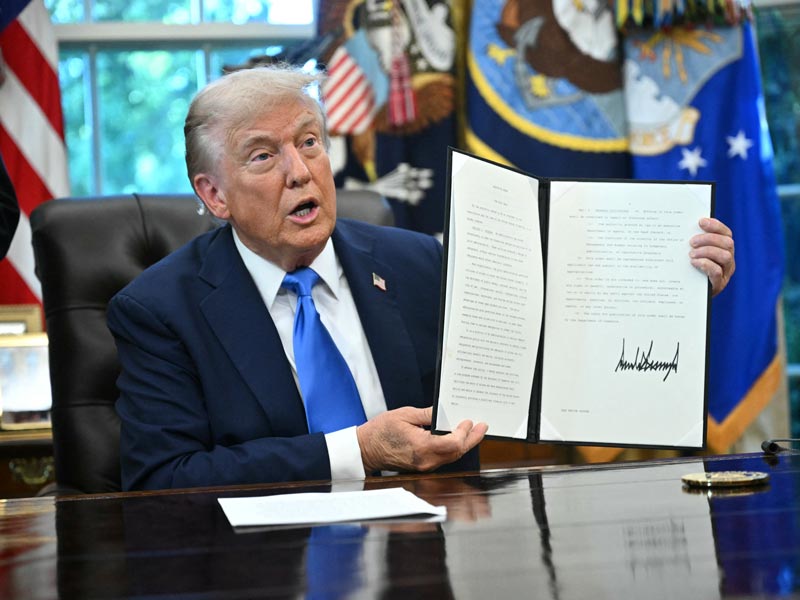

Central banks’ interest in gold is possibly driven by geopolitical risks. They are subsequently turning away from the US dollar to this particular commodity. Reports also suggest that another factor could be that the bond markets have also had a bumpy ride this year. However, in stark contrast, the FT also reports that Goldman Sachs predicts that gold could hit nearly $5,000 – particularly if US President Donald Trump undermines the Federal Reserve, as critics of his White House policymaking suggest.

Regardless, there is a global ease about budgets and central banks’ ability and willingness to keep inflation under control in the medium term. For example, during a press conference in September 2025, Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, and Luis de Guindos, Vice-President of the ECB, claimed that higher tariffs, a stronger euro and increased global competition are holding back growth; “However, the effect of these headwinds on growth should fade next year. While recent trade agreements have reduced uncertainty somewhat, the overall impact of the change in the global policy environment will only become clear over time.” The ECB hopes that it will be able to stabilise inflation at its two percent target in the medium term.

When capital stops chasing yield, it runs to permanence – and permanence is gold

Ugo Yatsliach, Founder of Gold Policy Advisor and a professor of economics at Bridgewater State University and of finance at Bunker Hill Community College, claims: “Central banks aren’t just worried about inflation – they are worried about a world where dollar assets can be sanctioned, seized or devalued.

“This is why central banks are paying a premium for gold, as it creates a politically neutral, seizure-resistant reserve portfolio. Dollar dependence is the underlying vulnerability. Treasuries and US funding still anchor reserves, but demand is falling, as competing blocs, parallel payment systems, and supply-chain realignment are eroding FIAT reserves and complicating monetary policy.”

With geopolitical and economic uncertainty being prevalent in their minds, gold is seen as a viable hedge – a strategic bet against geopolitical risk and central bank demand, marking what industry commentators suggest is a structural shift in global capital flows.

The Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum (OMFIF) suggests that geopolitical events have laid a solid foundation for gold “to become prominent once again in the reserve portfolios of central banks, and as a way to settle payments for some countries.”

Adding gold for diversification

Earlier in the year, AInvest reported that central banks added “410 tonnes of gold in H1 2025 (24 percent above the five-year average), with emerging markets leading diversification from dollar reserves.” It says investors have therefore been advised to allocate between five and 10 percent to gold via bullion or ETFs “as geopolitical risks persist, though dollar strength and policy shifts pose short-term volatility risks.”

A spokesperson for the European Central Bank told World Finance, “The ECB holds gold as part of its foreign reserves, and we recognise its historical and strategic significance in reserve management.” Beyond this, he said the ECB – just like the Bank of England – could not comment any further as they are unable to remark on specific market forecasts or on other central banks’ policies.

Nevertheless, Hugh Morris, Senior Research Partner at Z/Yen Group, finds the current level of interest in gold quite interesting. He claims that there is a “definite reversal of an historic trend because up until recently central banks have been net sellers rather than net buyers of gold.” However, President Trump has shaken them up a bit, accelerating and sparking concerns that there is too much dependence on the US dollar – making central banks and investors think they shouldn’t be overly dependent on it, even though concerns about this currency predate Trump.

Another driver is the fact that the world has become more insecure with more conflicts and more crises, such as the war between Russia and Ukraine, and in Gaza between Israel and Palestine. So, as gold has always been a hedge on economic and volatility impacts, he emphasises that gold, unlike other asset classes, remains a very certain asset.

He adds: “The last driver is groupthink. I see other central banks being busy buying gold, so that if they are asked by politicians or other central banks; ‘why are you not buying gold?’ They can respond that they have already been buying it. They want to be part of the in-crowd.”

Attractive to developing countries

Michael Bolliger, Chief Investment Officer Emerging Markets UBS Global Wealth Management, finds that gold is especially attractive to central banks in developing countries as they are trying to diversify their holdings while also hedging against economic, geopolitical and policy uncertainties.

“In recent years, emerging market central banks have been the largest buyers of gold, seeking assets that are less correlated with the US dollar and less sensitive to fluctuations in interest rates,” he explains before adding that this ongoing accumulation is expected to persist. This may be because these institutions are less price sensitive; they view gold as a stable store of value.

Emerging market central banks have been the largest buyers of gold

Bolliger suggests that there are also several reasons that have driven the gold price highs since July 2025. The first driver is the anticipation of further Federal Reserve interest rate cuts and persistent inflation. Together they have driven real interest rates lower in the US, making gold more attractive compared to interest-bearing assets. The US dollar has also weakened because the Fed is expected to ease policy, which he says enhances gold’s appeal for non-dollar investors.

To cap this, there is a robust investor demand, which is “evidenced by rising exchange-traded funds (ETF) holdings and strong central bank purchases.” This continues to support prices, and so while there was a very brief slowdown in the summer, “these underlying drivers, along with elevated geopolitical risks and policy uncertainty, have propelled gold to new highs,” he says.

Morris adds: “While Samuel Pepys may have buried some cheese during the Great Fire of London, most people buried gold. It is the go-to asset in times of uncertainty. There is one more interesting side effect of prolonged institutional buying of gold; it has broken the long-term inverse relationship between gold prices and interest rates. When interest rates were higher, traditionally, gold prices were lower. We are currently seeing relatively high interest rates and high prices of gold.”

China: A big gold buyer

Despite this, Eric Strand, Portfolio Manager of the AuAg Funds at AIFM, and their founder, claims that the Bank of England and the European Central Bank have been the least active in buying gold. “China has been a big buyer of gold, as well as other central banks in Asia, and now some European central banks have begun to do so – such as Poland,” he notes.

He claims that while Poland’s central bank sees the troubles in the system and acts accordingly, the Bank of England has historically often sold at the wrong time. In contrast, China and Russia are big gold producers and so they keep all their gold to add to their reserves. He adds: “We thought the US would count the gold they have, but this has still not materialised in the way that Trump wanted. At the same time there are questions about how much gold there is in Fort Knox.

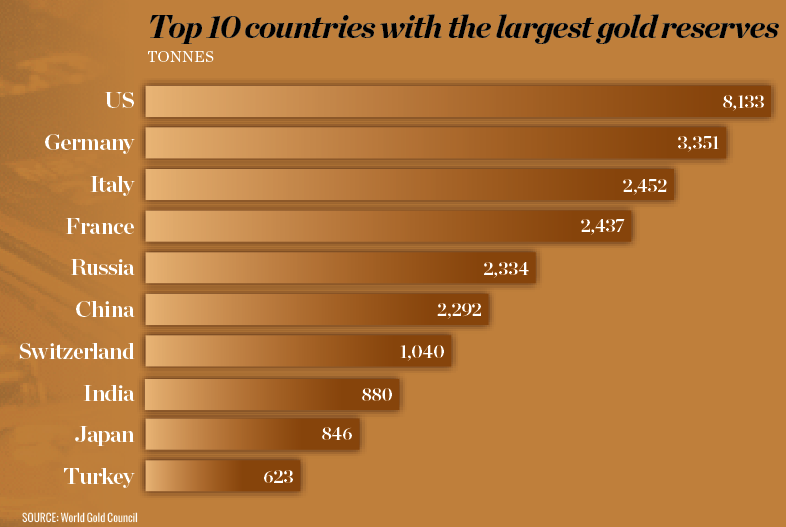

“It is a bit strange because the US had 16,000 tonnes of gold after the Second World War, and now they have about 8,133 tonnes of gold. They started to print a lot of money to finance wars. The deal was that the dollar was as good as gold, allowing for other countries to get paid in gold. The US had to ship half of their gold to Europe, leaving them with today’s unaccounted tonnes of gold. This led to a disconnection with gold in 1971 under President Nixon. That is the timeline for our new world order. Since then, all currencies are connected to the dollar, which has lost 98 percent of its value as measured in gold.”

The problem is that all FIAT currencies have been losing value since then. While central banks can print money to double its volume, such as for quantitative easing (QE), the very act of doing so can halve every unit of any given currency – whether it is the pound sterling or the US dollar. Then there is the need to service Sovereign debt. For example, Strand says the US is running up a seven percent deficit and so it is running on debt all the time. “The cost of servicing debt – including for defence – is the highest of all costs for the US and so this will force us back to much lower rates and probably all the way down to zero,” he argues.

He thinks that Trump needs to get interest rates down and as for the Federal Reserve, he suggests it is normally the first to act before claiming that it is currently behind the curve. Other central banks are ahead when it comes to interest rates. Meanwhile, Switzerland’s central bank is already down to zero percent. He therefore predicts that all central banks will be heading in the same direction. This is because it is the only way for countries to service their debt.

The trouble is that the Fed may return to QE control to get down the long rates, but Strand says this prospect makes the markets nervous as it is another way to print money. To him, that is a strong reason to own gold as QE only works in the short term. He believes that QE is the medicine that could be worse than the cure.

Shift in global capital flows

As to why there is a shift in global capital flows, Nicky Shiels, MKS PAMP’s Head of Research and Metals Strategy, stresses that confidence in historically safe assets, such as fixed income assets, has diminished considerably given the “extraordinary debt levels across most Western countries.” She says this has forced investors to reconsider their options or to re-think the traditional 60:40 portfolio, and to turn to assets such as gold, crypto or real estate. However, she warns that the pool of safe haven assets is shrinking.

Morris argues that the primary catalyst for the shift in capital flows is that the perception of risk is greater than the perception of opportunities in the market. He explains why he thinks this situation has arisen: “Companies that looked for high growth, high value investment opportunities – such as Third World manufacturing companies – are now being impacted by US tariffs.

“Investors are having to re-think where opportunity and risk may lie. The important driver of Trumponomics is that Trump’s view of economics is based on a zero-sum outlook, which is driven by a fundamental belief that the pie of opportunity is limited, and if I have a bigger bit, you have a smaller bit, and vice versa.” This is in contrast with the view of classic economics, which implies that there is no need to worry about the size of your slice of the pie, because it is important to worry more about the size of the pie you are taking your share from. This is because a smaller slice of a larger pie may, he explains, deliver a better outcome compared to a larger slice of a smaller pie. “Trump’s philosophy is based on a win-lose outcome, essentially: if you win, I lose, or I win, you lose, and he does not see a world where we can both win. That world view drives his policymaking,” he adds.

Weaponisation of the US dollar

This might be the case, but not everyone sees it as being about Trump’s policymaking. While he says he is not advocating for or against President Trump, Lobo Tiggre, CEO of Louis James, believes the biggest reason why central banks are turning to gold is the weaponisation of the US dollar by former US President Joe Biden in response to Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine in 2022. He claims this, and the sanctions that followed, were a shot heard around the world – not just by the rivals of the US.

He explains: “Even before Trump 2.0, allies understood that they were at risk entrusting their financial lifeblood to the US. This was a very big deal – the beginning of the end of the Bretton Woods accord. And now that Trump is waging trade wars against friend and foe alike, it has only added to the incentive for central banks around the world to diversify out of the USD and US treasuries.”

Yatsliach says capital is migrating from “yield at any cost” to “resilience at all costs.” He adds: “Falling demand for US Treasuries, dollar devaluation, and geopolitical tensions are making paper assets riskier investments, driving financial institutions to gold for protection.” He finds that gold’s appeal rises when the store-of-value function outranks the means-of-payment function: “Gold is liquid outside any single sovereign, and now a larger, steadier share of official demand than a decade ago. When capital stops chasing yield, it runs to permanence – and permanence is gold.”

As for China, the world’s second-largest US Treasuries holder, he says it has “decreased Treasuries holdings from $1.3trn to $765bn, while simultaneously strengthening their gold reserves” since 2011. The purpose behind this action was to diversify the country’s reserve holdings and to mitigate the risks of the US dollar’s weaponisation.

As for the US Federal Reserve, he remarks: “Fast forward to today, the global community sees the executive branch of the US government is seeking more influence over the Fed. This increases the perception of the dollar being used as a political tool, hence, the flight from dollars to gold – which is politically neutral. Politics is a catalyst, not the cause: it accelerates a diversification already in motion.”

The Trumpian shake-up

Morris agrees that President Trump is trying to change and shake up the current financial and economic system – in the US and globally. He says Trump is doing this by maintaining persistent pressure on the Fed to reduce interest rates to stimulate economic activity. He claims that other central banks are worried about these Trumpian tactics: “If the Fed does cut interest rates, there is already ample evidence that inflationary pressures are building in the US economy, and cutting interest rates aggressively would simply pour petrol on the flames.”

“Social media isn’t wrong, US policy is shifting,” comments Yatsliach. To him what matters is how US moves transmit globally through the US dollar, treasuries, and fund markets. “Any executive attempt by the US government to influence Fed governance and policy (appointments, high-profile clashes, unprecedented bids to remove a sitting Governor) generates uncertainty in the global markets,” he explains. The fear is that the president will have absolute power over the dollar, which is the anchor of the global reserve system. This is because it would become political rather than market driven.

Capital is migrating from yield at any cost to resilience at any cost

He adds: “What most don’t know is that the Gold Reserve Act of 1934 transferred ownership of all gold from the Fed to the US Treasury and created the Exchange Stabilisation Fund (ESF) – a fund designed to control the value of the dollar internationally. Section 10(a-c) gives the President and the Secretary of the Treasury discretionary power to deal in gold and foreign exchange, as well as the operation of a $2bn Exchange Stabilisation Fund (Gold Reserve Act of 1934, Pub. L. No. 73-87, § 10(a)-(c), 48 Stat. 337 (1934).

“The act also states that the President’s and Treasury Secretary’s actions are final and not subject to review by any other officer of the US. So, if a President succeeds in removing the sitting Governor of the Fed, and appoints someone under executive influence, the global monetary system would be subject to unprecedented executive influence from the US.”

Ultimately, this would decrease the independence of the Fed as it would become susceptible to the political agenda of the Trump administration. Consequently, this would raise the premium foreign central banks place on self-insurance. While central banks, he argues, don’t fear presidents, they fear the politicisation of the dollar as more political dollar funding can become more volatile. This is a critical concern for non-US banks such as the Bank of England and the ECB that borrow in dollars. They rely on the Fed’s swap lines, he explains, to backstop their stress.

“If the US loosens oversight and then hits turbulence, contagion can travel via derivatives, repo, and clearing networks into Europe,” he warns before adding: “For the ECB especially, volatility in core rates and the dollar can complicate monetary transmission and re-ignite fragmentation risks inside the euro area. Tariffs can move yields, the dollar, and risk premia, directly affecting the value of other central banks’ dollar reserves. When the anchor currency looks political, every central bank’s insurance policy is gold.”

Gold: Rising out of risk?

Can gold ride out the geopolitical and economic risks better than the US dollar and treasury bonds? Morris argues that they are completely disconnected. That is because gold is an asset in times of uncertainty. Nevertheless, he predicts that bonds and other interest-linked instruments will continue to command premium returns because of the levels of uncertainty and risk in the world. “Currently we are seeing high interest rates and a high price for gold; both driven by the levels of risk and uncertainty in the world, but independently of each other,” he expounds.

Bolliger responds by highlighting that in recent years gold has outperformed many other asset classes, including the US dollar and US Treasury bonds, “and as long as investors remain preoccupied with geopolitical concerns as well as political and policy risks, we think gold can continue to outperform safe haven assets such as the US dollar and US Treasury bonds.” He adds that UBS wishes to stress that gold price can also see fluctuations during “risk-off events as investors liquidate assets and hide them in (US dollar) cash.”

As for the Goldman Sachs prediction that gold could soon hit nearly $5,000, Strand suggests that anything below $4,300 is cheap with regards to the deficit and Sovereign debt situation. While he thinks that $5,000 sounds high, although it’s only 25 percent from $4,000, gold will continue to rise. He is sure that the Fed will need to lower interest rates, allowing gold to fly. He therefore agrees that the Goldman Sachs scenario is realistic. Much depends on how fast the central banks print money or perform QE. Whatever happens, while there is uncertainty, people will continue to invest in gold.