United no more?

As the United Nations turns 80, the organisation is coming under pressure to reform in order to stay relevant. But can the UN adapt to the financial and political challenges of today’s world, while staying true to its founding mandate?

In the summer of 1945, leaders from 50 nations gathered in San Francisco to sign the United Nations Charter, pledging to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war.” This powerful promise, written as the world was reeling from the horrors of the Second World War, would serve as the guiding principle for the new United Nations – an intergovernmental body established to promote peace and cooperation in the fragile post-war period.

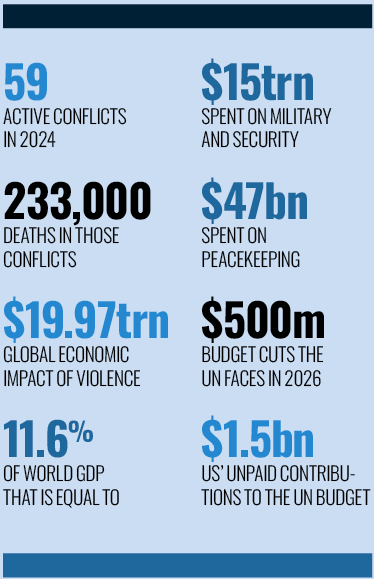

Now, 80 years on from its ratification, the foundational pledge of the UN is coming under increasing strain. This year, devastating conflicts in Gaza, Ukraine and Sudan have made it seem that global peace is moving ever further out of reach. The world is now experiencing its highest level of conflict since the Second World War, with 59 active conflicts and an estimated 233,000 associated deaths in 2024. Each ongoing conflict brings with it untold suffering, while the economic impact of this violence now stands at $19.97trn, representing 11.6 percent of global GDP. According to the Global Peace Index, nations spent $15trn on military and internal security costs – a figure that dwarfs the $47bn spent on peacekeeping and peacebuilding.

With so much at stake, the UN is coming under increasing pressure to deliver on its foundational pledge and reaffirm its position as a powerful peacekeeper. As the organisation marks a landmark anniversary, can it find a way to reassert itself on the fragmented global stage?

A force for good

Since its creation, the United Nations has demonstrated its ability to deliver on its peacekeeping pledge and has played a vital humanitarian role in some of the world’s most dangerous and devastating conflicts. Over the last 80 years, the UN has helped to end conflicts and support mediation efforts in dozens of countries, from the Middle East to Central America. In 1988, the United Nations Peacekeeping Forces were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for ‘preventing armed clashes and creating conditions for negotiations,’ highlighting the UN’s central role in fostering collaboration and lasting peace.

When accepting the award, the then Secretary-General, Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, told the Oslo audience that the essence of peacekeeping “uses soldiers as the servants of peace, rather than the instruments of war.”

By providing basic security guarantees in crisis situations, the UN’s peacekeeping forces have been able to stabilise fragile regions and support peaceful political transitions in regions blighted by conflict. In Mozambique, the organisation played a significant role in facilitating the transition from civil war to peace after a devastating 16-year conflict. After the signing of the 1992 Rome General Peace Accords, the UN deployed the United Nations Operation in Mozambique (ONUMOZ), to monitor the ceasefire, oversee the demobilisation of troops and support peaceful post-conflict elections. Backed by some 6,500 UN troops and military observers, the ONUMOZ operation helped to transition Mozambique to a multi-party democracy and establish the vital foundations for long-lasting peace.

Similarly, the United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) played a crucial role in supporting Namibia’s transition to independence in 1989 and 1990. Namibia, then known as South West Africa, had been illegally administered by South Africa for decades, with years of armed insurgency displacing thousands of civilians and causing widespread violence. After establishing a ceasefire between warring parties, the UN began to deploy peacemakers to the region, to monitor the withdrawal of South African forces and ensure that safe and fair elections could be held. Despite the complexities of the mission, UNTAG was able to successfully establish a peace plan that emphasised local ownership of the nation’s transition to independence. Today, the operation is regarded as one of the most successful peacekeeping missions in UN history and serves to illustrate how the organisation can positively change the trajectory of a nation – when it is operating at its best.

The pressures of peacekeeping

The UN’s historic peacekeeping missions show that when properly resourced, adequately funded and politically supported, the organisation can achieve real success in regions blighted by conflict. This success, however, is by no means guaranteed. Without sufficient powers or legitimacy, peacekeeping missions can falter, leaving civilians vulnerable to a resumption of violence. In the 1990s, atrocities in Rwanda and Bosnia illustrated the limits of international interventions.

The United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) entered Rwanda in 1993, with a mandate to enforce the Arusha Accords peace agreement, which was meant to bring an end to the nation’s bitter civil war. With just 2,500 troops and a limited budget, the mission was hampered from the very outset. Despite a growing awareness of the violent intentions of armed militia groups in the country, the UN Department of Peacekeeping operations did not permit mission troops to disarm or demilitarise these groups, with peacekeepers unable to act proactively to prevent the mass killings that followed.

With many UN member states unwilling to commit to a larger, more robust intervention in the region, the ill-equipped and outnumbered UNAMIR troops were insufficient to address the unfolding humanitarian crisis. Between April and July 1994, militia groups are estimated to have killed between 800,000 and one million people, marking one of the darkest moments in the history of international peacekeeping. A little over a year later, Dutch peacekeeping troops were unable to stop the massacre of 8,000 Muslim men in Srebrenica, a town that was supposed to be a UN-protected ‘safe area’ for Bosnian civilians. The lightly armed Dutch unit were easily overrun by Bosnian Serb forces, in what was the largest massacre on European soil since the UN’s founding. In the years since, the organisation has recognised “the failure of the United Nations and the international community to prevent this tragedy.” Thirty years on from these atrocities, the UN says that important lessons have been learned from the failures of the 1990s. Adequate resources are essential to any peacebuilding mission, as is effective leadership and a clear, robust mandate. Heeding early warnings and acting preventatively is vital to addressing violence before it escalates. And for peacekeeping to be more than immediate crisis response, missions should be locally grounded, with local leaders taking ownership of the long-term peace process. These are lessons learned at a painful price. But despite the UN’s vows to avoid the mistakes of the past, its current paralysis in the face of widespread violence and war is once more prompting concern over its ability to fulfil its peacekeeping mandate.

Fit for purpose?

As conflicts rage around the world, the need for peacekeeping and peacebuilding is high. Despite providing vital humanitarian support in crisis-ridden regions, the UN has been seemingly powerless to intervene in some of the world’s bloodiest conflicts. The veto powers of the Security Council’s five permanent members – China, France, Russia, the UK and the US – have stymied the organisation’s ability to respond to major crises, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s war in Gaza.

Since launching its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia has continued to use its veto power to block action by the Security Council, stirring debate about the body’s effectiveness and ability to defend international peace. These discussions have been further amplified by the repeated US vetoes on resolutions on Gaza. Amid a worsening humanitarian crisis in the Gaza strip, the US voted against ceasefire resolutions on six separate occasions, leaving UN peacekeeping at a standstill in the war-torn region. Sidestepping any UN-led efforts, President Trump has instead forged ahead with his own 20-point plan for peace in Gaza, undermining the organisation’s long-running endeavour to secure collective agreement on conflict resolution in the region. With the UN seemingly unable to intervene in high-stakes scenarios, many are now questioning whether the Security Council may be ripe for reform.

The body – which is primarily responsible for maintaining international peace through resolutions, peacekeeping missions and sanctions – has remained largely unchanged since its founding in 1946. Increasingly, its make-up is thought to be unrepresentative of the international community and the evolving geopolitical environment. Since its formation, the council’s elected membership has grown modestly from six elected members to 10, while its permanent membership remains the same as in 1946. Regional powers and member states from the developing world have been calling for a stronger voice at the council, with some seeking to secure permanent seats of their own. Greater representation may well give the body enhanced legitimacy in the eyes of the international community, with the council better able to reflect the current geopolitical landscape, rather than the post-Second World War political order.

Critics also argue that the increasing use of veto powers is limiting the council’s functionality. While France and the UK have not used their veto since 1989, China, Russia and the US have been using their veto powers more frequently in recent years. Since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Russia – often joined by China – has used its veto power close to 20 times to block resolutions that would protect Syrian civilians suffering under the Bashar al-Assad regime. Since the 1970s, the US has used the veto far more than any other permanent member of the council, with the majority of its most recent vetoes relating to resolutions on Israel’s war in Gaza. The recent uptick in vetoes by the permanent five is reflective of the fractured times we are living through.

With members increasingly at odds with each other, last year the Security Council passed just 41 resolutions – the lowest number since 1991. As differences and disagreements hold the UN back, how can the organisation make good on its basic principles of peace, security and cooperation?

Future-proofing operations

As the UN celebrates its 80th anniversary, it feels right to reflect on its role on the global stage. The world of today is very different to that of 1945, and the UN needs to ensure that it can adapt to an era of rising political tensions and budgetary pressures.

“This is a good time to take a look at ourselves and see how fit for purpose we are in a set of circumstances which, let’s be honest, are quite challenging for multilateralism and the UN,” said Guy Ryder, Under-Secretary-General for Policy for the UN, at the launch of the ambitious UN80 Initiative.

The system-wide reform programme seeks to modernise the UN and improve its efficiency across the board, enabling the organisation to remain effective, cost-efficient and responsive to today’s global challenges. Taking a three-pronged approach to reform, the initiative will look at improving internal efficiencies by cutting red tape, as well as reviewing the organisation’s 40,000 mandate documents to see what can be prioritised and deprioritised. The last and arguably most ambitious workstream looks at whether “structural and programme realignment are needed across the UN system,” in order to simplify operations going forward.

“Eventually, we might want to look at the architecture of the United Nations system, which has become quite elaborate and complicated,” said Ryder.

This bold, far-reaching initiative is a clear statement of intent for the UN, signaling its aspirations to transform itself into the peacekeeping power that the world needs today. Shrinking budgets and growing geopolitical divides are placing ever-increasing strain on the organisation, and the UN will need to adapt to these pressures if it is to stay relevant in today’s fragmented world. Long-standing criticisms of the organisation’s structure – including its limited Security Council membership – may need to be addressed if the reform process is to be fully inclusive and transparent. These are not simple changes for an organisation as complex as the United Nations to make, but the need to revitalise and reinvigorate the UN is more pressing than ever before. As the organisation is increasingly sidelined in primary peacemaking, and faces repeated attacks on its legitimacy from US President Donald Trump, the UN must strengthen its resolve and reaffirm its commitments to its core values, while responding to the demands of today.

“We will come out of this with a stronger, fit-for-purpose UN, ready for the challenges the future will undoubtedly bring us,” Ryder said of the initiative.

Feeling the strain

Of the many challenges facing the UN, its funding shortfalls may be the most acute. The organisation will need to cut an estimated $500m from its 2026 budget and lose up to 20 percent of its staff as it looks to cope with a huge reduction in funding from the Trump administration. Against this worrisome backdrop, it is hard not to conclude that the UN80 Initiative may be driven by a need to dramatically cut costs.

When properly resourced and politically supported, the UN can achieve real success

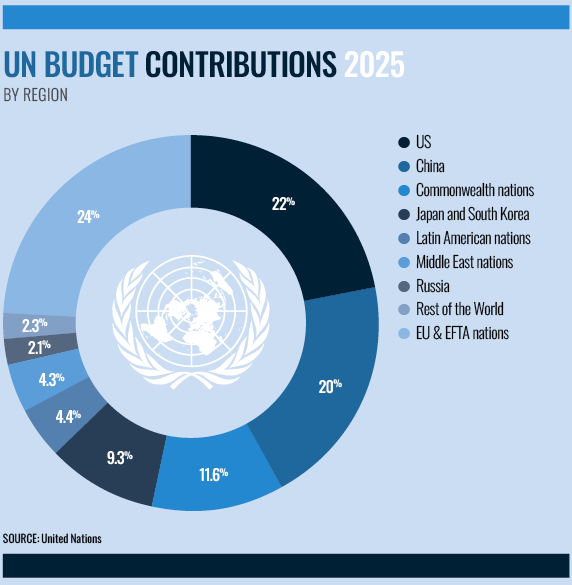

The UN’s liquidity issues primarily stem from member states failing to fulfil their financial obligations, leaving a substantial budget shortfall and cash deficit. While the US is the largest debtor, owing approximately $1.5bn in withheld funds, it is far from the only member state to miss its regular payments.

Last year, 152 nations out of 193 member states paid their full UN contributions by the deadline of December 31, while in 2023, that number was just 142. Delayed and missed payments to the UN regular budget – which covers core administrative and operational costs – are placing ever-increasing strain on the organisation, while many countries are also slashing their foreign aid budgets, with devastating effects on humanitarian and peacekeeping operations.

The impact of funding cuts on important, life-saving programmes is already becoming apparent. The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has warned that it may need to cut or suspend essential services in crisis-afflicted regions such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Bangladesh, putting the health of 13 million displaced people at risk. The UNHCR health budget has been cut by 87 percent compared to 2024, with devastating consequences for some of the world’s most vulnerable people.

The UN’s Nobel Prize-winning World Food Programme (WFP) may also be forced to scale back or halt its life-saving operations, even as hunger crises around the world deepen. With its budget falling 34 percent in 2025, the WFP has said that it will be forced to reduce emergency food assistance, affecting up to 16.7 million people facing food insecurity and famine. Yemen faces the most severe cuts to its food aid system, with 4.8 million people at risk of losing life-saving support. In Cameroon, WFP resources are already at critically low levels, placing half a million refugees at risk of hunger and malnutrition. Elsewhere, HIV and AIDs support programmes in Tajikistan are suffering from shrinking support, as are protections for women and girls in crisis zones across Africa and the Middle East.

“Budgets at the United Nations are not just numbers on a balance sheet – they are a matter of life and death for millions around the world,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres told reporters at the UN80 Initiative launch. While the proposed structural changes of the UN80 Initiative will not ease the pain of budget cuts on the UN’s life-saving humanitarian work, they may well help the organisation to make some valuable savings through increasing effectiveness and efficiency. In this new era of dramatically reduced foreign aid funding, every penny counts.

A changing world

There is no doubt that international diplomacy is in a very difficult place. Decades-long relations are fraying, as major powers are increasingly pursuing their own interests. If the old order of Pax Americana is truly dead, then President Trump’s speech at the 80th United Nations General Assembly might have been the final nail in its coffin. The theme for the 80th session was ‘better together,’ but Trump’s speech spoke of a deeply divided world. Over the course of an hour, the US president took aim at his opponents, saving his most scathing criticisms for his hosts. Repeating his much-disputed claim that he has personally ended seven wars in the last seven months, Trump accused the UN of inaction and “empty words.”

“What is the purpose of the United Nations?” he asked in his wide-ranging speech. “It has such tremendous potential but it is not even coming close to living up to that.”

By its own admission, the UN could indeed stand to strengthen its position and improve its ability to respond to today’s challenges. But what Trump’s speech failed to acknowledge was how repeated attacks on the UN are contributing to a wider erosion of trust in global institutions. For decades, multilateral bodies such as the UN have been able to bring parties around the table to work out collective solutions to the most complex global problems. Even in the most testing times, the organisation has served as a platform for dialogue, collaboration and collective action, encouraging unity over isolationism.

The UN must strengthen its resolve and reaffirm its commitment to its core values

In today’s fragmented and militarised global landscape, trust in the multilateral system is faltering. The UN’s legitimacy and effectiveness is under ever-increasing scrutiny – and this scrutiny is curtailing the UN’s ability to act. Without strong political support from its member states, the UN’s role on the global stage will be inevitably diminished.

“Multilateralism is under fire precisely when we need it most,” said Guterres in his first year as UN Secretary-General. “We need stronger commitment to a rules-based order, with the United Nations at its centre.”

Simply put, the world needs more collaboration, not less. History has taught us that isolationism often leads to insecurity and instability, with civilians left to pay the price of these political decisions. For all its flaws, the United Nations remains the most important forum for collective action on the complex challenges facing the world today. As it celebrates its 80th birthday, renewed political will may be the greatest gift the UN can ask for.