Going against the stream

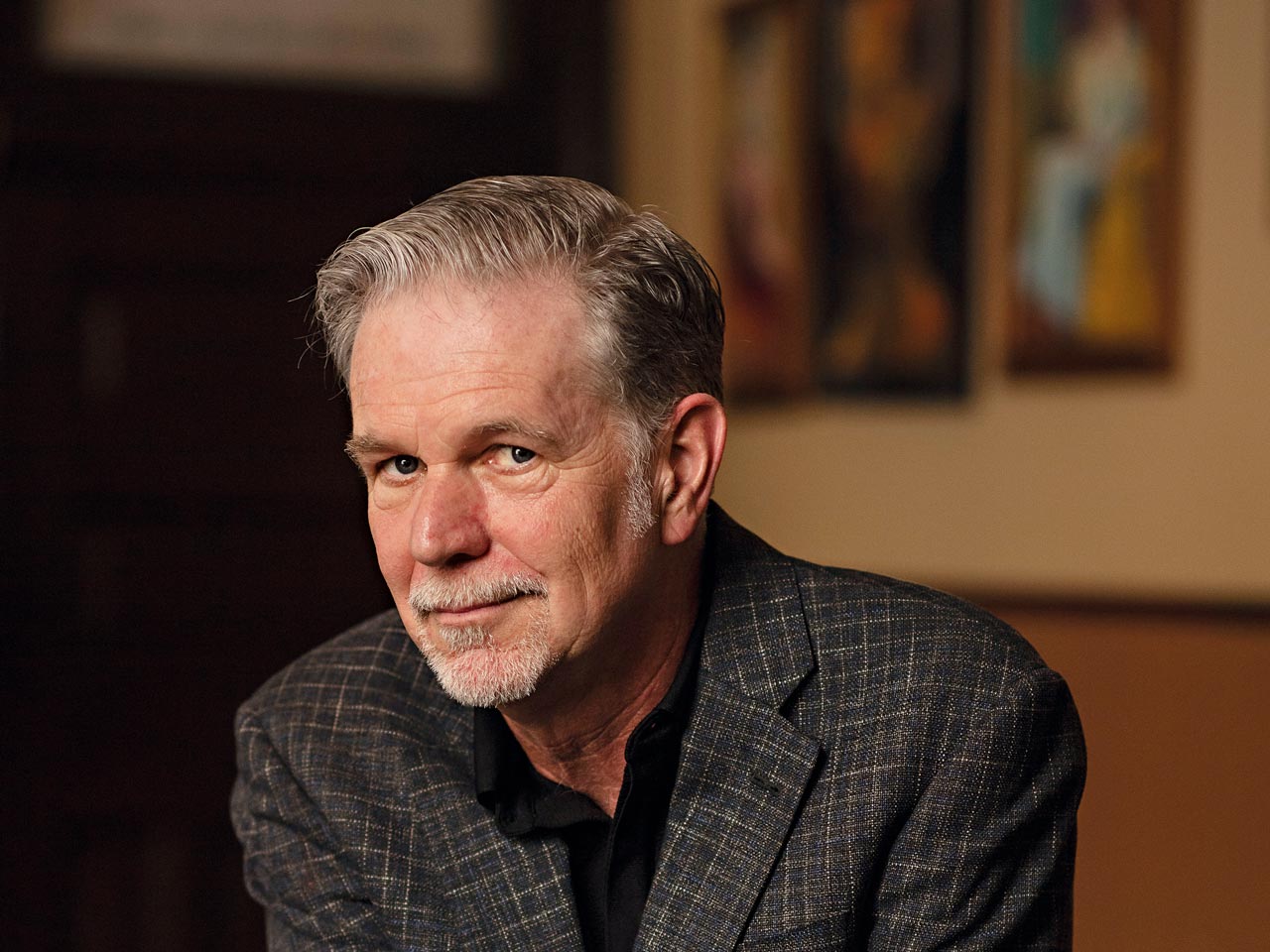

Reed Hastings brought streaming to the masses with Netflix, but as more competitors crop up, can he keep the business at the forefront of the industry with his plan to supercharge original content and offer customers a cheaper, ad-supported service?

In 1997, so the story goes, Reed Hastings spent the best $40 of his life. At the time, he was frustrated. He had just returned a rented copy of Apollo 13 six weeks late and was slapped with a huge late fee. Why, he wondered, could the price of renting films not be more like a gym membership, where you pay a flat price to work out as much or as little as you want? At the time, DVDs were a new but untapped technology poised to explode in the US market. Not only were they a burgeoning market, but they were also perfectly sized for slipping into post boxes. Off the back of his fine, Boston-born Hastings dreamt up a business model for mail order movies. With one start-up already under his belt, he would go on to found DVD-by-post turned streaming behemoth Netflix within the year.

Twenty-five years on, Hastings’ origin story has become legend in the world of business. However much truth is in it, his success is undeniable. Netflix, which turned over nearly $30bn in 2021, has gone from plucky, cult-status start-up to Silicon Valley veteran. Hastings steered the ship through periods of choppy waters, but with questions over just how long he will remain at the helm and where he will take Netflix in the so-called ‘streaming wars,’ World Finance looks back on his legacy.

Don’t listen to the sceptics

While Netflix would be Hastings’ big lightbulb moment, it wasn’t his first spark of brilliance in the business world. After earning a mathematics degree from Bowdoin College – he “found the abstractions beautiful and engaging,” he later told The New York Times – Hastings went on to earn a master’s degree from Stanford in computer science. By 1991, at the age of 31, he had co-founded his first business, Pure Software, with Raymond Peck and Mark Box.

The business, which originally offered a debugging tool for engineers, was a success. Revenue doubled each year before it went public in 1995, Hastings told Inc. magazine, and it was soon snapped up by a competitor, Rational Software, for $750m. The deal wasn’t particularly well received by Wall Street, but Hastings didn’t worry about what others thought. “I was doing white-water kayaking at the time, and in kayaking if you stare and focus on the problem you are much more likely to hit danger,” he told The Times. “I focused on the safe water and what I wanted to happen. I didn’t listen to the sceptics.”

After inspiration for Netflix struck, Hastings wasted no time in making his idea a reality. In 1997, he launched the business with co-founder and entrepreneur Marc Randolph.

Winning the rental wars

In its first year, Netflix gained 239,000 subscribers, and it wasn’t long before its red DVD envelopes became ubiquitous in the United States – and beyond. Hastings made waves by situating the business at the cutting edge of entertainment and technology. While Netflix first offered a pay-per-rental model for each DVD, by 2000 it had a monthly flat fee in place, nixing the need for late fees and due dates. “It was still a dial-up, VHS world, and most video stores didn’t carry DVDs, so we were able to sign up early adopters,” he told Inc.

The business went from strength to strength in the run-up to its initial public offering in 2002, when it listed its stock at $15 per share.

The company posted its first profit the next year, earning $6.5m on revenue of $272m. By 2004, its profits had ballooned to $49m, and in 2005 it was sending out a million DVDs every day. But 2005 marked the time of peak DVD in the US market, with sales reaching a height of $16.3bn. For Hastings, the next goal was to move into video streaming. He told Inc. that same year: “We want to be ready when video-on-demand happens. That’s why the company is called Netflix, not DVD-by-mail.” But the transition wasn’t without its problems. In 2011, Hastings announced Netflix would divide its DVD and streaming businesses into separate subscriptions with separate fees – and names. The streaming service was to retain the name Netflix while the DVD side would be renamed Qwikster. Neither customers nor the markets were happy, and Netflix’s share price fell 75 percent by the end of 2011, according to Forbes. After initially doubling down, Hastings eventually cancelled plans for Qwikster.

Despite the missteps, Hastings was winning the film rental wars. In 2010, Blockbuster, which once had 9,000 video rental shops in the US, filed for bankruptcy after being crushed by nearly $1bn in debt and torn apart by internal disputes. Blockbuster’s demise occurred just a decade after Hastings and Randolph offered to sell their business to the video rental giant for a mere $50m. Following the meeting, which took place during the dot-com bubble, former Netflix CFO Barry McCarthy said Blockbuster executives had “laughed us out of their office.”

Throwing out the rulebook

At Netflix, Hastings is known for being a hands-off leader. “Incredible people don’t want to be micromanaged,” he once told Forbes. “We manage through setting context and letting people run.” Hastings currently shares responsibilities with co-CEO and chief content officer Ted Sarandos, who became joint head of the company in 2020, having worked at the business since 2000.

In 2020, Hastings published No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention with business school professor Erin Meyer. The book outlined his leadership philosophy and how it plays out at Netflix. “We wanted to make the case that it’s good business to run without rules – which is a surprising statement,” he told Variety. The key, he said, is “embracing managing on the edge of chaos. And as long as you are tolerant of managing on the edge of chaos, of course there’s going to be some mistakes” – take Qwikster, for example – “but there’s also going to be a lot of innovation.”

Netflix’s annual leave policies are one case study of the ‘no rules’ strategy. Hastings plays the long game with employees, encouraging them to take time off via unlimited vacation policies and unlimited parental leave, in the hopes that any loss in efficiency will be regained by employee loyalty and innovation. “We’re willing to take some inefficiency narrowly and in edge cases to create an environment that’s extremely flexible because we think that outperforms in the long term,” he told Entrepreneur. Hastings said he takes six weeks off per year, explaining at The New York Times DealBook Conference that the time away from work “hiking some mountain” or “reading something not connected to work,” helps him get a different perspective and provides inspiration.

But it’s not all positives with the ‘no rules’ philosophy, and Hastings admits it’s not a perfect strategy. Some of Netflix’s policies have been challenged for creating a culture of fear. The infamous ‘keeper test’ is a process where managers are told to consider if a person on their team were to quit whether they would try to get them to change their mind or whether they would accept the resignation, perhaps even with relief. If their answer is the latter, they may as well send them packing now and look for someone they would fight to keep, the ‘keeper test’ advises.

“Think of a great athlete,” Hastings told Variety. “You kind of know you could get injured, maybe even a career-ending injury, in every game. But if you think about that and if you obsess on it, it’s only going to hurt you. So we have to hire the psychological type that can put that aside and who aspires to work with great colleagues and that’s their real love, is the quality of their colleagues or the consistency of that, versus the job security.” If job security is your priority, Hastings said Netflix’s message is clear: “We’re not a good place to come. We don’t want people to feel debilitating fear; obviously that’s not productive.” But, he said, Netflix is looking for “a special kind of person who can ignore that fear.”

Hastings believes this strict approach to weeding out mediocrity is key to maintaining Netflix’s competitive edge and innovation. He saw the alternative at Pure Software. “We stopped being innovative. We were all about process. And then the market shifted, and we were unable to pivot and ended up selling to our largest competitor,” he told Variety. “So it ended up as a really good success financially, but it did not become an epic, world-changing company in the way we want to make Netflix.”

Changing tack

Flexibility and innovation are important to keeping Netflix’s offering fresh and its business model agile, but the business’s recent change in strategy regarding advertising is more akin to a U-turn. Hastings had long committed to keeping advertisements off the platform, with Netflix’s chief financial officer saying advertising was “not in our plan” as recently as March 2022. But in April, Netflix reported its first quarterly decline in subscriber numbers in more than a decade, and a tumbling stock price forced a swift rethink. Now, the streaming giant’s plan is to funnel in more subscribers through its cheaper, ad-supported service.

The television advertising industry was buoyant on the news, with Brian Wieser, president of business intelligence at WPP-owned GroupM telling the Financial Times that Netflix poses “a great untapped audience.” And the advertising world, which brings in more than $60bn a year, offers an equally large opportunity for Netflix. However, Netflix has to battle the perception that by offering an ad-supported service, it is compromising its brand. As Rich Greenfield, an analyst at LightShed Partners, told the Financial Times, “It is scary if the only way to reinvigorate growth is offering cheaper products that worsen the consumer experience, essentially making it more like the dying linear TV experience.”

Being an entrepreneur is about patience and persistence, not the quick buck

Hastings himself has admitted that advertising is no fast-track to growth. “Advertising looks easy until you get in it. Then you realise you have to rip that revenue away from other places because the total ad market isn’t growing, and in fact right now it’s shrinking,” he told Variety in 2020. And in a 2019 letter to investors, the business said, “We believe we will have a more valuable business in the long term by staying out of competing for ad revenue and instead entirely focusing on competing for viewer satisfaction.”

Market researcher Kantar noted in a July report that streaming growth was most significant in paid ad-supported streaming and free ad-supported streaming, while paid streaming without ads grew at a slower rate.“Value is increasingly important to retaining streamers as platforms are competing for screen time or risk being cancelled and replaced,” said Nicole Sangari, vice president of Entertainment on Demand at Kantar Worldpanel Division. “This upward trend of significant [paid and free ad-supported streaming] growth is correlated to high stacking [of multiple subscriptions]. As stacking reached new heights, consumers were willing to reduce their overall streaming costs for ads. Streaming has gone full circle, once being the destination to avoid cable TV ads, to increasingly relying on ads to drive growth.”

Of Netflix’s ad-supported tier, Sangari said the move was a “suitable strategy to combat losing subscribers due to its cost and value.” Offering an ad-supported tier “can help win back its lost subscribers,” she said, as customers who had planned to cancel their subscriptions can switch to a cheaper service instead. However, as the business fights password sharing, it is expected to lose customers. “Their strategies are having lingering effects on how loyal customers perceive its features and value.”

While Netflix teeters on the unknown, two of its rivals, HBO Max and Hulu, have seen growth. “The platforms have focused on cost-savings to prove value and created a content niche that over time they expanded: HBO Max with new releases and Hulu with next-day cable to Hulu TV series,” Sangari said. “Both started by offering something unique to the market, and with greater competition have focused on diversifying their offerings to drive engagement.”

Changing the world for good

While Netflix’s shift to ad-supported advertising is welcomed by some industry experts, seeing Hastings’ commitment to ad-free viewing crumble overnight may cause investors to wonder if other commitments will be dropped. From live news and sports to gaming, there are a multitude of ways Netflix’s content offering could shift.

Speculation over when Hastings will leave Netflix is also emerging. With Sarantos sharing the position at the head of the business and making the big calls on Netflix’s content, Hastings appears to be putting the wheels of a succession plan in motion. In a recent earnings call he suggested he would be leaving the business by 2030. But he insists he’s committed to Netflix. “What I don’t want people to think is that I’m checking out,” he told Variety. “I guess it is the beginning of the end in the sense that eventually, I’ll be gone. At least for the next decade, I’m super-excited by what we’re doing and full-time, so it was a statement that it’s not a short-term situation.”

Outside of his work at Netflix, Hastings is known for his philanthropy and political contributions. Through Netflix, Hastings accumulated a substantial fortune. In 2017, he was added to Forbes’ 400 list of the richest people in America, with the group estimating his fortune sat at $5bn. Between 2001 and 2011, Hastings spent $8.1m on political donations in California, according to the Silicon Valley Business Journal. In 2020, he donated $1.4m to Joe Biden’s presidential campaign, Business Insider reported, having previously gifted $89,000 to Barack Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign.

Hastings and his wife, producer Patty Quillin, also joined a philanthropy pact founded by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett to give away the majority of their fortune. “It’s an honour to be able to try to help our community, our country and our planet through our philanthropy,” Hastings and Quillin said in a statement at the time. “We are thrilled to join with other fortunate people to pledge a majority of our assets to be invested in others. We hope through this community that we can learn as we go, and do our best to make a positive difference for many.”

Education has been a consistent theme in Hastings’ philanthropy, and he has made a pledge to spend $100m of his fortune reforming the US public school system. In 2020, he and Quillin gave $120m to fund scholarships for black students through a partnership with two historically black colleges in the US and the United Negro College Fund, and he also spent $20m building a training facility for teachers. “Being an entrepreneur is about patience and persistence, not the quick buck,” Hastings told Inc. in 2005. “If we can transform the movie business by making it easier for people to discover movies they will love and for producers and directors to find the right audience through Netflix, and can transform public education through charter schools, that’s enough for me.”

The streaming wars

Netflix has indeed transformed the movie industry. Not only the way films were delivered, but also through the content itself. In 2012, the business produced its first TV series, House of Cards, which went on to receive over 56 Emmy nominations, winning seven. Since launching the political thriller, a stream of critically acclaimed successes has flowed from Netflix’s original content production machine, including Stranger Things, The Crown, Bridgerton and Sex Education.

Netflix has proven it has significant strengths in the market, despite losing subscribers

Netflix’s streaming service has now expanded into 190 countries, and the business’s next aim is to become content king. In the second quarter of 2022, Netflix commissioned 160 film and TV show titles in total, with most of the originals being produced outside of the US. “What’s next is becoming a great Turkish developer of content, becoming a great Egyptian developer of content, and sharing that with the world,” Hastings told Variety. Indeed, content is one differentiator in the ongoing streaming wars. “Netflix has proven it has significant strengths in the market, despite losing subscribers. It has the content and easily navigable interface to keep subscribers engaged,” Kantar’s Sangari said.

The use of streaming services continues to grow. The proportion of US households with streaming services reached 88 percent as of June 2022, according to Kantar, with 113 million households accessing streaming products. According to the research, the average household has five subscriptions to streaming services. But Netflix’s competitors aren’t confined to its streaming peers, according to Hastings. In 2017, Hastings said Netflix’s biggest rival wasn’t Amazon or traditional broadcasters, but sleep. “You know, think about it, when you watch a show from Netflix and you get addicted to it, you stay up late at night,” he said. In 2019, he said video games were causing the business to lose more subscribers than rivals. “We earn consumer screen time, both mobile and television, away from a very broad set of competitors. We compete with (and lose to) Fortnite more than HBO – there are thousands of competitors in this highly fragmented market vying to entertain consumers.”

But Hastings isn’t afraid of a little competition, and he is confident of Netflix’s position, even as rivals like Disney+ make bigger gains in subscribers. In a recent letter to shareholders, the business effectively said it was winning the streaming wars: “Our competitors are investing heavily to drive subscribers and engagement, but building a large, successful streaming business is hard – we estimate they are all losing money, with combined 2022 operating losses well over $10bn, vs. Netflix’s $5bn to $6bn annual operating profit.”

Hastings said it himself: he isn’t in this for the quick money. He wants to build a “world-changing” company – one subscription at a time.