Back from the brink

In the wake of the 2008 financial meltdown, Greece became the epicentre of Europe’s most perilous economic drama – a decade-long struggle that tested the limits of the euro, shattered economies and reshaped the continent’s financial order

Of all the crisis meetings around the world in the wake of the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the US and the onset of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, the one in Athens was the most significant. And it was a meeting that would go on, in various forms, for a decade. The attendance in Athens in late 2009 comprised European banks that were on the hook for billions in euro loans to Greece that were on the verge of default, experts from the European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund, European politicians who feared the collapse of the euro, and members of an abject Greek government whose profligacy had landed the parties in this precarious position.

There was one main burning issue on the table: the survival of the euro, the 10-year-old currency that had, uniquely, been designed by committee instead of emerging organically like sterling or the dollar. But some even feared the crisis could lead to the collapse of the entire European experiment.

As the main players got around the table, the situation was desperate. Greece was on the brink of bankruptcy and currency traders were mercilessly attacking its sovereign debt while also doing their level best to undermine other highly indebted nations, notably Ireland and Portugal.

The stakes could hardly have been higher. Under the Stability and Growth Pact agreed in the 1990s, member countries had formally agreed to pursue mutually responsible economic policies – fiscal discipline, in short. No country was allowed to print money without reference to Brussels, borrowing was to be tightly controlled and inflation closely managed. Most EU members had more or less followed the rules, but not Greece.

Greece had misrepresented its finances before it even joined the eurozone

As the Peterson Institute for International Economics explains: “Despite the pact, the Greek government racked up years of deficits and excessive borrowing after adopting the euro in 2001.” That is, two years after its official launch. However, Greece was flagrantly breaking the rules and concealing it, a deceit helped by prevailing and unusually low interest rates on its sovereign bonds. This was contrary to the normal behaviour of government debt when a country runs persistent and large deficits and it assisted Greece in pulling the wool over Brussels’ eyes.

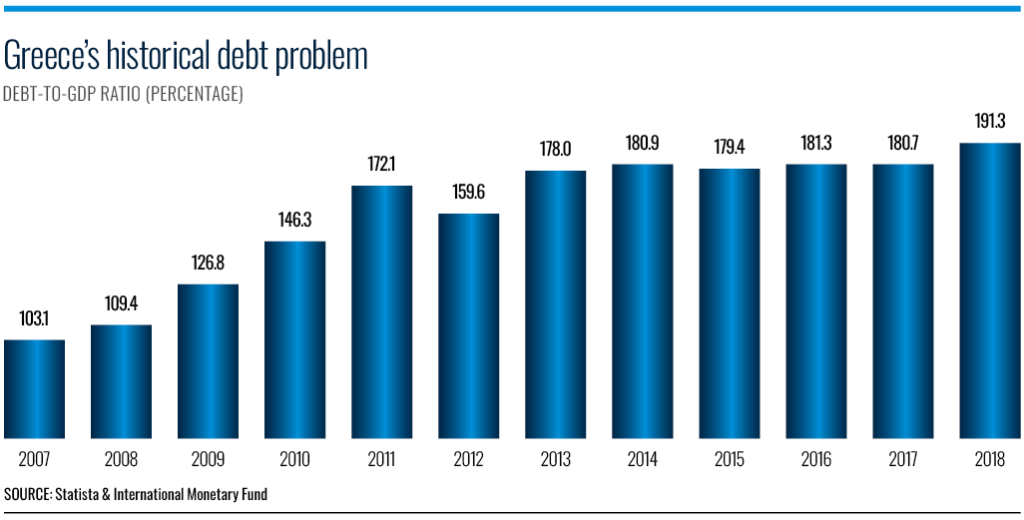

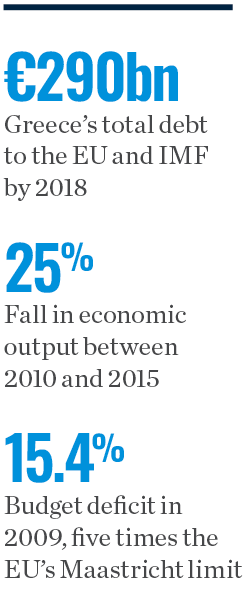

As the Council on Foreign Relations would explain years later in a timeline of the drawn-out crisis, Greece had misrepresented its finances before it even joined the eurozone. “Its budget deficit was well over three percent and its debt level about 100 percent of GDP,” the council pointed out, also citing Goldman Sachs’ role in helping Greece conceal part of the debt through complex credit swap transactions. Greece wasn’t the only EU country to misbehave, economically speaking, but it was certainly the most irresponsible. As the IMF would explain in a paper years later: “Pensions and social transfers increased by a whopping seven percent of GDP from the time of euro adoption to the eve of the crisis, while the public wage bill rose by three percent of GDP. This drove the overall fiscal deficit from four percent in 2000 to more than 15 percent of GDP in 2009 – a staggering five times the Maastricht [official] limit.

And so Greece’s private lenders, most of them French and German, blithely continued to throw money at the country. The standard explanation for their failure to spot the danger was a general misunderstanding of the rules of the eurozone. As the Peterson Institute surmises: “Financing institutions may have assumed that any country with a borrowing crisis would be bailed out. They were complacent in the face of Greek deficits. The government’s borrowing spree helped to pay for public services, public wage increases and other social spending. Its borrowing was hidden by budget subterfuge. Warnings about its condition went largely unheeded.”

Summer Olympics

Some began to worry though when Greece hosted the 2004 summer Olympics at a cost of €9bn and when more public borrowing sent the deficit to over six percent and the ratio of debt to GDP to 110 percent. “Greece’s unsustainable finances prompted the European Commission to place the country under fiscal monitoring in 2005,” recalls the council.

It was the general election of 2009 that opened the Pandora’s Box of Greece’s profligacy and triggered a descent into economic chaos. A new socialist government under George Papandreou revealed that the budget deficit was heading for over 12 percent of GDP, nearly double the original estimates. But even that was too low – soon it would be revised to 15.4 percent. At that point credit rating agencies abruptly downgraded Greece’s sovereign debt to junk status.

By 2011 the money markets were thoroughly rattled. “Bond markets started to lose confidence in Greece’s economy,” explains the Peterson Institute, in something of an understatement. This loss of confidence turned into despair when private lenders in France and Germany belatedly realised that the EU had no formal system for bailing out a sick member, as Greece had manifestly become. That meant that Greece could no longer roll over its debts because the banks refused further loans for fear of good money following bad. Hence the EU’s most economically recalcitrant member could not plug the gaps in its budget shortfalls. The alarm bells ringing all over Europe, the IMF and ECB had to hurriedly step in along with the EU’s economic trouble-shooters in what became known as ‘the troika.’ None of these institutions had faced a crisis of this magnitude.

Contagion

The immediate and looming threat was the risk of contagion in a European banking system already in trouble in the wake of the 2008 bank collapses that precipitated the Great Financial Crisis. Many institutions bore heavy losses and they had no appetite for shovelling further debt to Greece. Having mistakenly assumed all debt to member countries was risk-free, they had compounded their error by also assuming that Greece’s central bank had sufficient capital to absorb a Greek default.

Financing institutions assumed that any country with a borrowing crisis would be bailed out

Suddenly the banks, the troika and everybody else on the sidelines of these increasingly fraught negotiations were deeply aware of a long-held principle among central bankers. Namely, moral hazard. In simple terms this meant that, if profligate nations were bailed out, other economically delinquent governments would expect the same favours. “All banks in Europe feared that Greek debt relief would set a precedent,” notes the Peterson Institute. “Bonds issued by other European governments suddenly became risky.”

In consequence the cost of debt began to rise for other EU members. The Peterson Institute: “Almost overnight this made it more expensive for these governments to borrow. Loss of investor confidence was infecting the entire European financial system.” Contagion really was setting in.

The economic lines were drawn. On one side experts feared that the Greek economy would be strangled if the politicians imposed excessively punitive measures. On the other most EU politicians and, it seems, the troika were determined to send a message: “Germans and others in Europe felt that Greece had to suffer the consequences of its alleged misbehaviour.” Stuck in the middle were hapless Greek citizens. As the economy foundered and punitive measures were indeed enforced, they rightly blamed their government for misleading them. All too soon Greece’s economic woes spilled into the streets as rioters in Athens rallied against hefty budget cuts and tax increases that were triggering high unemployment, shrunken living standards and slashed social services. Simultaneously, populist politicians over much of the EU were attacking the EU, which, they argued, was suppressing their national identities.

Athens deal

The immediate source of Greek citizens’ anger was the Athens deal, a three-year bailout scheme agreed in mid-2010. In this the IMF and EU threw Greece a €110bn lifeline repayable over three years. The price was austerity measures including €30bn in spending cuts and tax increases. This was an all-out assault on the deficit put together by the IMF and other, mostly reluctant, EU nations that already had quite enough financial troubles of their own. Spain for instance was just about overwhelmed by a real-estate crisis while Portugal was suffering from its own economic mismanagement. The ECB also stepped in by buying up heavily discounted Greek bonds on the secondary market in what it called the Securities Market Programme. This was an unprecedented move, but ECB president Mario Draghi promised the bank “would do whatever it takes.”

The programme allowed Europe’s top central bank to absorb the government bonds of other struggling sovereigns. “This was to boost market confidence and prevent further sovereign debt contagion throughout the eurozone,” explains the Council. In fact the contagion was spreading so fast that EU finance ministers also agreed rescue measures worth nearly $1trn to hard-hit eurozone countries.

But austerity didn’t work for Greece. After a brief rally when the deficit sank to five percent of GDP, an encouraging improvement, the inevitable occurred. The Greek economy was stripped so bare that it fell into decline and there were not the funds to meet the loans that still hung over the country like a sword of Damocles.

Deauville deal

Two years after the Athens deal, the situation was once again so dire that the risk of a Greek default was back on the table. German chancellor Angela Merkel and French president Nicolas Sarkozy led a new programme that became known as the Deauville Deal. “If the euro fails, Europe will fail,” declared Merkel.

This time the banks – ‘irresponsible lenders,’ according to the parties involved in the deal – were told to accept their share of the punishment in the form of discounting the value of their loans. In short, they had to take a haircut. But as the Peterson Institute acknowledges: “The Deauville announcement rattled bond markets further. Banks feared having to take haircuts on the value of their loans. Bond yields spiked, making the prospect of a timely return of Greece to market borrowing even more remote.” The banks were strong-armed into submission. Facing complete write-offs or haircuts, most of the private lenders opted for the latter rather than be party to a complete default.

This second bailout handed Greece €130bn, but the country’s private lenders took a beating – a 53.5 percent write-down. Greece’s side of the bargain was to slash its debt to GDP ratio from 160 percent to just over 120 percent by 2020. It was the largest restructuring of its type in history. Simultaneously, all but two EU members – Britain and the Czech Republic – signed the Fiscal Compact Treaty designed to keep their economic behaviour in line. The crisis had now dragged on for four years – and then it got worse.

Although, in 2013, Greece finally posted a surplus, it was a technical one described as a “small primary fiscal surplus, the fiscal balance excluding interest payments.” Just when the authorities were ready to applaud, the economy plummeted to an even lower level, with economic output down by 25 percent compared with 2010, which had been bad enough. Unemployment hit 27 percent. And debt to GDP ratio shot up from the 130 percent of 2009 to 180 percent by the end of 2015.

The patient was even sicker. About 25,000 public servants from an admittedly bloated bureaucracy were laid off and the labour unions, whose members had taken a beating, called a general strike. As more rational economists had argued years before, if the purpose of the rescue measures was to help Greece repay its debts, as it surely was, it had demonstrably failed. Clearly, only a healthy economy could produce the revenues that enabled it to climb out of trouble.

The composition of Greece’s debt was now unrecognisable from before the rescue attempts. Nearly all of it lay in the hands of a variety of European and international institutions such as the European Financial Stability Facility and the ECB, which was on the hook for long-term debt of up to 30 years.

Behind the scenes the ECB was deeply involved. It had issued more than $1.2trn in quantitative easing – effectively the printing of credit – to boost a moribund European economy.

Next crisis

Then in 2015, to the horror of Brussels, angry and disillusioned Greek voters installed a left-wing government under the Syriza party and another crisis promptly ensued. Of all the crisis years, this would be the most fraught and raise the probability of ‘Grexit,’ Greece’s departure from the eurozone. As many now said, it should never have been allowed to join in the first place.

New prime minister Alexis Tsipras had the backing of unions and he promptly attacked the troika over austerity measures, demanded relief from the mountain of debt and an end to austerity. An aghast Brussels flatly refused, insisting that Greece work through the original arrangements before coming back to the table. When the Tsipras government missed a €1.6bn repayment to the IMF, negotiations between Greece and its official creditors deteriorated rapidly. To stem the flight of capital from the country, Tsipras had already limited bank withdrawals to just €60. Eventually though, the prime minister had to bow to Greece’s obligations to creditors and, despite a referendum that overwhelmingly rejected austerity measures, he signed a third bailout deal with up to €86bn after a tense weekend of negotiations in August 2015 in which Greece was nearly kicked out of the eurozone.

The price this time was wholesale economic reform whereby the government agreed to introduce tax reforms, cut public spending even further, privatise state assets and deregulate the labour market. Just to keep an increasingly divided government on track, the €86bn was to be spread over three years.

Interestingly, the ECB sat in on the negotiations but refused further loans. Obviously, the central bank thought it had done enough.

Turn of the tide

Two things now began to turn the tide – the less draconian terms of the latest rescue package and long overdue economic reforms. In 2016, Greece provided a pleasant surprise by posting a large budget surplus of almost four percent. Almost miraculously, unemployment began to decline, albeit slowly. Then in 2017, the economy started to grow for the first time in eight years.

Yet the recovery was too slow for Greeks, who voted the socialists out. Although the tide was turning, the accumulation of rescue debt had reached proportions that horrified most economists. By 2018, Greece owed the EU and IMF alone about €290bn. Like a dark cloud over the country’s future, successive governments were expected to run budget surpluses for the next 42 years! The size of the Greek economy had crashed by nearly a quarter and faced a long uphill recovery.

This was much worse than had been thought at the outset of the crisis exactly a decade earlier. The IMF’s Poul Thomsen, director of the European department, painted a dark picture to an audience at the London School of Economics in 2019: “We had assumed that it would take Greece eight years to return to pre-crisis level. This was as bad as in the United States Great Depression in the 1930s, and considerably worse than the four years that it took countries affected by the Asian crisis.

“The outcome was much worse. Today, almost 10 years later, GDP per capita is still 22 percent below the pre-crisis level. We forecast that it will take another 15 years, until 2034, to return to pre-crisis levels. Under the Commission’s forecast it will take until 2031.” So where had the rescue missions gone wrong?

on international bailout terms

In the rationally argued view of Poul Thomsen, the enforced measures had reduced the economy so severely that it could not pay its way out of trouble. Basic public services could not be provided and capital spending was so low that any prospect of growth was rendered just about impossible. As tax increases were piled on already high rates, tax collections had slumped from 65 percent in 2010 to about 41 percent in 2017 while – the opposite of what was needed – well over half of all wage-earners and pensioners were exempt from paying any personal income tax at all. And somehow much-needed reforms of one of the EU’s most generous pension schemes had been abandoned along the way.

For most Greeks, the troika and the IMF in particular had become the whipping boy. Yet contrary to the populist rhetoric, the IMF had not insisted on more austerity. Instead the organisation had argued that Greece should not be asked to deliver unreasonably high surpluses but should be required to fix its problems with pensions and taxes so that the economy could recover more quickly. In short, go for growth.

The IMF’s overall explanation for Greece’s painfully drawn-out crisis was political. “Contrary to other crisis-hit countries, there was no broad political support for the programme from the outset,” concludes Thomsen, citing various parties’ failure to unite behind the measures. In Portugal, which faced similar problems, there was broad political support for the rescue on both sides of the aisle.

But the IMF does not absolve itself of blame. The architects of the various rescue missions simply expected too much too soon from an economy with so much self-inflicted damage. But lessons had been learned and salvation was at hand.

The great recovery

To the relief of Greece’s 10.4 million people, by early 2025 GDP was growing faster than the eurozone average and had been for four straight years. Moreover, it was expected to do so until at least 2027. The volume of public debt was down. Unemployment had fallen to historically low levels of just under 10 percent, albeit high by European standards, but half a million new jobs had been created in six years. The all-important primary surplus had hit 4.8 percent, more than twice as high as predicted. And the days of junk status for bonds were over – in 2023, Greece’s sovereign debt was restored to investment grade in a red-letter day for the country’s beleaguered central bank.

There is work still to be done, according to a late 2024 survey by the OECD that cited low productivity and reluctant business investment still scarred by the Great Financial Crisis. But the worst is definitely over. In an event that nobody would have predicted in the dark days of 2009, in May 2025 Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis accepted an award at an economic conference in Berlin for what most economists were calling a remarkable recovery.

No longer Europe’s problem child on the brink of “crashing out of the eurozone,” as he put it, “Greece is being recognised for its determination, its discipline, its resilience and its ability to implement difficult reforms.” Still, it was a close-run thing.