Race to the bottom: The reckless rush to mine the deep sea

As the race for critical minerals heats up, companies and governments have set their sights on the mineral-rich deep sea. But what is the environmental cost of extracting these resources – and is it really worth the risk?

Imagine diving into the deep blue waters of the open ocean, approximately 500 miles southeast of Hawaii. At first, there would be some sunlight, but this would soon fade as you begin your descent. By about 650 feet, there is no longer enough light for photosynthesis to occur, and by 3,000 feet, light no longer penetrates at all. You have entered a strange new world, one where remarkable creatures have adapted to the crushing pressure and constant darkness.

Once you hit 12,000 feet, you have reached your deepwater destination. This is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, a vast abyssal plain as wide as the continental US. Little is known about the creatures that live at these depths, with over 88 percent of the region’s species thought to be entirely new to science. But as well as being rich in marine life, the zone is also home to another source of extraordinary value – untapped stores of critical minerals.

Seabed mining represents a step into a fragile and vulnerable unknown

According to some studies, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone could contain more cobalt, nickel and manganese than all terrestrial reserves combined, making it an area of extreme interest for mining companies and governments alike. Back on dry land, the global race for critical minerals is heating up. Considered to be the ‘new oil’ powering the international economy, rare earth elements and critical minerals are needed for much of our modern technology, and will be crucial to fuelling the green energy transition in the years to come. As a result, demand for critical raw materials is soaring – and so is competition. In a bid to get ahead in the race to the seafloor, US president Donald Trump recently signed an executive order aimed at fast-tracking deep-sea mining activities in both American seas and international waters. The controversial move has been widely condemned by scientists and environmental campaigners, who are concerned about the impact of commercial seabed mining on some of our world’s most ecologically important habitats. Yet despite alarm bells ringing on all sides, the Trump administration looks set to forge ahead with activities on the seafloor, in an effort to “counter China’s growing influence over seabed mineral resources.” But as the US looks to the deep sea as its next geopolitical battleground, it risks sailing into uncharted waters.

Treasures of the deep

For decades, miners and traders have theorised about the mineral treasure trove of the world’s seabeds. Now, for the first time, mining technology might be ready to make their vision a reality. Commercial deep-sea exploration is gaining momentum, with nations including China and India carrying out mining tests in both territorial and international waters. And while commercial-scale seabed mining is yet to begin in earnest, 2025 could be a defining year for the controversial practice.

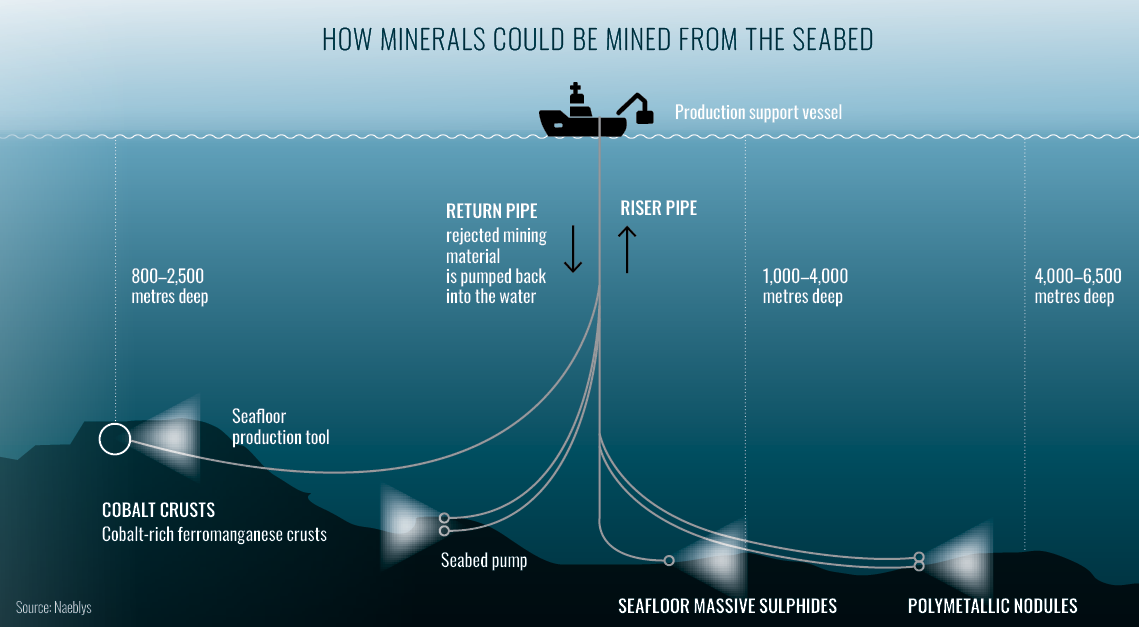

Amid the great rush for critical minerals, private companies and politicians are turning their attention to the deep sea, where significant reserves of precious metals can be found in potato-sized ‘polymetallic nodules’ on the ocean floor. First discovered in Siberia’s Kara Sea at the end of the 19th century, these slow-forming nodules contain rich concentrations of metals, including nickel, cobalt, copper and manganese.

The scientific expeditions of the HMS Challenger in the 1870s found evidence of polymetallic nodules in most of the world’s oceans, with clusters covering more than 70 percent of the sea floor in some locations. Now, over a century on from the Challenger expeditions, economic interest in these mineral-rich nodules is gaining traction.

Exploratory deep-sea mining began in the 1970s, and in 1994, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) was established to regulate mineral-related operations on the international seabed. As of 2025, the ISA has granted 31 contracts for ocean-floor exploration, with China, Russia and South Korea leading the pack. Taken together, these contracts cover over 1.5 million square kilometres of the seabed – representing an area four times the size of Germany. With companies working up further plans for full-scale commercial operations, it seems that the race to the bottom of the sea may now be underway, despite concerns that the risks of deep-sea mining are not yet fully understood.

Mining at the earth’s surface is an extremely destructive process. The extraction of minerals from the earth involves extensive clearing of land, and can result in habitat destruction and biodiversity loss, as well as the contamination of soil and groundwater. Once extracted, minerals must then be processed before use – a water-intensive operation that releases carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. If surface-level mining is any indication, the mining process for the deep sea will be both intensive and invasive. Deploying heavy mining equipment on the seabed would disturb delicate ecosystems that have – until now – been largely untouched by human activity. And, with the deep sea holding many mysteries, seabed mining represents a step into a fragile and vulnerable unknown.

Life finds a way

The deep sea is the largest ecosystem on the planet, accounting for around 90 percent of our oceans. But its high pressure, constant darkness and perpetual cold conditions make it a challenging environment for us land-based mammals to access, as very few research vessels are capable of surviving the journey into the deep, dark abyss. Despite decades of study, the deep sea remains poorly understood, with 80 percent of our oceans entirely unexplored. What scientists are certain of, however, is the abundance of life in the deep.

It was once thought that life without sunlight was impossible, but the 19th century brought a host of breakthrough discoveries that challenged this long-held belief. Then in 1977, a team of marine geologists made a discovery that would completely redefine our understanding of requirements for life in the deep sea: hydrothermal vents. Found on the ocean floor in more volcanically active areas of the globe, hydrothermal vents can be thought of as underwater geysers, releasing a steady flow of heat and chemicals into the water around them. Here, large clams, human-sized tube worms and other unique organisms are able to thrive by converting chemicals from the vents into energy, in a process known as chemosynthesis. Thanks to these underwater hot springs, rich ecosystems are flourishing in even the most extreme conditions. With new organisms regularly being discovered in the deep, scientists now believe that as many as 10 million different species may live in waters deeper than 200 metres. And while life at these depths is plentiful, it is also fragile.

The economic merits of deep-sea mining are still far from clear

The extraordinary creatures of the deep are delicate organisms, and are more sensitive to change than those living in the shallows. Slight shifts in temperature, oxygen levels or pH can have a significant impact on organisms that have adapted to the stable environment of the deep ocean. Life also moves at a slower pace in the deep, with organisms taking a long time to grow, and recovering slowly from any disturbances. Polymetallic nodules are thought to take tens of millions of years to reach the size of a small potato, with some scientists estimating a growth rate of between one and three millimetres per million years. These nodules are an important habitat for many deep-sea fauna, and their removal or disruption could drastically unbalance this delicate ecosystem.

Above the seafloor, deep-sea mining may have other unintended consequences for marine life. The light pollution from mining vessels could be disruptive and disorientating to organisms that have adapted to minimal sunlight. Ocean noise pollution already impacts how marine mammals communicate and navigate, and increased noise from heavy machinery could further threaten whale and dolphin populations that rely on sound to feed, migrate and reproduce. Discharge and waste products from intensive mining activities could spread over vast distances, posing a threat to open ocean fish. Plumes of fine sediments are already known to damage respiratory and feeding structures in fish, and could easily be stirred up by collector vehicles working on the seabed. While the full impact of mining this vast and mysterious environment is still uncertain, it is clear that it would have significant and long-lasting consequences that stretch far beyond the seafloor.

Crossing the rubicon

Even as scientists and campaigners sound the alarm bells on deep-sea mining, interest in the controversial practice continues to grow. In April, President Trump signed an executive order to increase seabed mining activities in US and international waters, marking his latest bid to increase America’s access to critical minerals.

The order, which is unprecedented in its support for the practice, directs federal agencies to expedite the process for reviewing and issuing permits for mining the seafloor, both in US waters and in “areas beyond national jurisdiction.” Once implemented, the order will make it easier for private companies to begin commercial mining operations in earnest – essentially allowing them to proceed outside of any international frameworks.

While the ISA has set regulations on seabed mining, the US is the only major global economy that is not a member of the organisation, and does not recognise its authority. For years, the ISA has been working on a mining code, which would set further international standards for deep-sea mining operations. This long-delayed code would require all seabed mining activity to adhere to rules on waste products, discharge depths and environmental mitigations when occurring in international waters. The organisation is set to meet in July of this year, with a view to finalising its code, but Trump’s executive order gives little heed to these ongoing negotiations.

In fact, the order appears to bypass any burgeoning multilateral agreements on deep-sea mining, in a move that China says violates international law. “The US authorisation violates international law and harms the overall interests of the international community,” Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Gu Jiakun said after the order was signed.

The race to the ocean floor is as much about political power as economic necessity

And China is not alone in its criticism of Trump’s push into international waters. The executive order puts the US at odds with the rest of the world on this issue, as mounting environmental concerns have started to curb initial enthusiasm for the controversial practice. In December, the Norwegian government announced a one-year pause on its plans to start mining its seabed, after previously voting overwhelmingly in favour of launching seabed operations. Elsewhere, more than 30 countries – including Germany, Spain, Canada and the UK – have called for a 10-year moratorium on the practice, while French president Emmanuel Macron has backed a complete ban on deep-sea mining. A growing number of private companies also support a pause on seabed mining activity, with car manufacturers such as BMW, Renault, Volvo and Volkswagen all pledging not to use deep-sea minerals in their vehicles. Tech giants Google and Samsung have also announced their support for the global moratorium, promising not to use seabed minerals in their supply chains until the environmental risks are “comprehensively understood.”

Amid these growing calls for caution, the US is set to take a very different path. But even as the Trump administration gears up to fast-track permits, the economic merits of deep-sea mining are still far from clear.

Need or greed?

Supporters of deep-sea mining argue that they are motivated by economic necessity. It is true that the global demand for minerals is growing, and access to raw materials is becoming increasingly politicised in this new era of heightened US protectionism. By some estimates, demand for minerals could increase by nearly 500 percent by 2040, as countries race to scale up their decarbonisation efforts. Yet it is important to remember that demand forecasting is not an exact science. Projections are subject to highly changeable factors, including economic shocks and shifting consumer demand. The future needs of the rapidly evolving technology sector are particularly difficult to predict, given the current pace of change. Advances in artificial intelligence, machine learning and robotics have increased the pace of change tenfold, making long-term demand forecasting ever more challenging for analysts.

Emmanuel Macron

Indeed, despite warnings of a global scramble for lithium, nickel, copper and cobalt, supply has largely outstripped demand in recent years. Global production of lithium hit a new high in 2024, but weaker-than-expected demand for electric vehicles contributed to a surplus of almost 154,000 tonnes of the mineral last year alone. Similarly, a boom in the Indonesian nickel industry has seen three consecutive years of oversupply, and nickel prices have almost halved since 2022 as a result. Production of cobalt continues to exceed demand, with prices plummeting to their lowest level since 2016, while the copper market is facing its largest glut in four years.

Along with overproduction, shifting trends in the tech sector have impacted the global minerals market of late. Cobalt has traditionally been a key component in many electric vehicle batteries, but some manufacturers are now moving towards battery designs that use more sustainable elements. Tesla, the world’s second-largest manufacturer of electric vehicles, already uses cobalt-free batteries in half of its fleet, while other leading firms are pioneering their own new battery chemistries. Recycling technologies are also becoming ever more efficient, helping to relieve pressure on future demand for critical minerals. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), a successful scale-up of mineral recycling could reduce the need for new mining activity by 25 to 40 percent by 2050.

In EV production and beyond, these shifts are having a significant impact on mineral supplies, prompting analysis to question whether deep-sea mining is really necessary to meet demand. Studies indicate that there is no real shortage of mineral resources on land, but for some proponents of seabed mining, the economic lure of the deep sea is hard to resist. The Trump administration estimates that deep-sea mining could boost US GDP by $300bn over a 10-year period, and create approximately 100,000 jobs. Even if this vision is realised, however, any economic benefits will surely come at a great environmental cost.

Troubled waters

As mining companies ready themselves for their first deep-sea operations, it is becoming increasingly clear that the race to the ocean floor is as much about political power as economic necessity. On dry land, Beijing dominates global supply chains of critical minerals and rare earths. According to the IEA, China accounts for 61 percent of rare earth mineral production and 92 percent of their processing, giving it a near monopoly over the supply of some of the world’s most valuable raw materials.

“While the Middle East has oil, China has rare earths,” the former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping famously declared on a visit to one of Inner Mongolia’s largest mineral mines. Since the 1980s, China has been ramping up its rare earth mining activities. Decades of state-backed investment in its domestic processing industry have established China as the global leader in critical minerals, able to effectively decide which countries and companies receive supplies of these crucial resources.

Amid the ever-escalating US-China trade war, Beijing has dramatically curbed its mineral exports to the US, revealing just how dependent America is on these vital imports. Across the Atlantic, meanwhile, the EU is similarly reliant on China for many critical minerals, including 100 percent of its heavy rare earth metals. In an era of heightened geopolitical tension, this high level of dependency leaves the bloc vulnerable and exposed to global economic shocks.

While the EU and the US are both looking to become more self-sufficient in mineral extraction and processing, it will be difficult for any major power to challenge China’s dominant position in the critical mineral sector – at least at sea level. By setting its sights on the ocean floor, the Trump administration may be seeking to reshape the balance of power on the global stage.

“We want the US to get ahead of China in this resource space under the ocean, on the ocean bottom,” a US official told the BBC upon the signing of the controversial order.

Potential exploitation

In the ongoing Sino-American trade war, the international seabed could become the next geopolitical arena. Until now, deep-sea mining tests have followed the ISA framework, but Trump’s executive order may set a new precedent. If implemented, the order could allow commercial companies to effectively bypass the multilateral regulations imposed by the ISA, opening up the international seafloor to potential exploitation.

The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea recognises that the ocean floor is ‘the common heritage of mankind,’ and that it is ‘beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.’ Significantly, the US stands alone as the only major economy that has not ratified the treaty, and now appears to be creating its own rules on exploiting seabed resources. If other nations follow suit and break with the Law of the Sea treaty, then a scramble for the international seafloor could commence.

Our oceans make all life on Earth possible, and are home to delicate ecosystems that we are just beginning to comprehend. The exploitation of these resources is not just an economic question – it is an existential one. As companies ready themselves to take the plunge, we risk causing irreversible damage to the very heart of our planet. Whether we are willing to further endanger the health of our oceans for the sake of winning the minerals race is something all nations ought to carefully consider. The fate of entire ecosystems depends on the decisions we make today – and there is no going back.