JP Morgan suggests that $5trn will be spent on the build-out of data centres worldwide from 2026 to 2030, while McKinsey expects that the total investment could reach $7trn during the same period. In aggregate, these forecasts imply a base-case annual capital expenditure of $1trn. Headline figures vary across financial institutions and consulting firms. Their guesstimates, however, all point in the same direction.

To put the scale of this annual capex into perspective, Bank of America estimates that it costs $50bn to build one gigawatt (GW) of data centre capacity. At that rate, $1trn of annual investment would fund approximately 20 GW of new capacity, three times New York’s installed electricity capacity of roughly 6.7 GW.

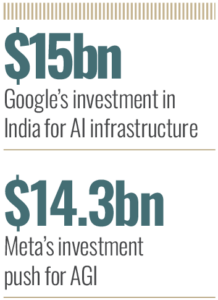

Silicon Valley, meanwhile, seems to move fast to meet this goal. 2025 has just witnessed a web of circular financing deals in which hyperscalers and fast-growing AI unicorns increasingly investing in each other, blurring the line between customers, suppliers, and investors. OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank has committed $500bn for their Stargate project over the next four years while CoreWeave signed a $14bn deal with Meta to supply computing power, to name just two examples. According to Goldman Sachs, the consensus capex estimates for AI hyperscalers alone might reach $394m by the end of 2025.

The million-dollar question is how such investment will ultimately be financed. For hyperscalers such as Meta, this size of commitment in AI investment is consistent with the scale of their balance sheets. The route to funding such investment is less clear, however, for standalone AI developers. OpenAI generated approximately $20bn of annual recurring revenue (ARR) in 2025, yet the AI poster child has committed to invest $1.4trn over the next eight years, according to Sam Altman.

To answer this question, it is useful to examine how AI investment has been funded to date. Hyperscalers funded early AI investment with their own cash flows. In 2025 alone, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet collectively sit on around $500bn free cash flows. Then the debt capital market was tapped as this once-in-a-lifetime technological breakthrough in the 21st century started to appear promising. Constrained by balance-sheet leverage ratios, they started to shift debt off balance sheet recently.

A case in point is Meta’s Hyperion Data Center in Louisiana. In October 2025, Meta announced a joint venture with Blue Owl Capital to develop this project through a special-purpose vehicle (SPV) called Beignet Investor. According to the Financial Times, this SPV has raised $30bn in total, comprising $27bn of loans from private credit funds and $3bn of equity from Blue Owl.

Looking ahead, Morgan Stanley addressed the funding question in a report published in July 2025. The bank estimates that capex in data centres by 2028 could reach approximately $3trn, half of which could be covered by hyperscalers’ own cash flows. A further $200bn could be funded by corporate debt issuance. Specifically, it points out that another $150bn could be funded via data centre asset-backed securities (ABS) and commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS).

Data centres have already been financed off balance sheet

Data centres are not new to the securitisation market, but their use of structured finance remains limited. The first-ever data centre ABS in the world was issued in February 2018 by Vantage Data Centers, a data centre operator in key US markets. Rated A- by Standard & Poor’s, the securitisation notes raised $1.125bn, allowing Vantage to expand in existing and new markets. Three years later, Blackstone issued the first-ever CMBS in 2021, raising $3.2bn to finance the its $10bn acquisition of data centre operator QTS Realty Trust in June 2021.

For computing power ABS and potentially more exotic financing vehicles to emerge at scale, clearer evidence of AI monetisation might be required

In Europe it is still at its early stage as there are only two ABS deals so far. In June 2024, Vantage raised £600m in securitised term notes regarding two data centres located in Wales, UK, making the first-ever data centre ABS in Europe. One year later, it issued another €640m in securitised term notes in June 2025 for four data centres located in Frankfurt and Berlin, Germany, the first-ever data centre ABS in continental Europe.

According to the New York Times, 27 data centre ABS deals have been issued raising $13.3bn in 2025, increased 55 percent year-over-year.

Why computing power is structurally securitisable

At present, data centre securitisation deals are all issued by data centre operators, with long-term contractual cash flows from tenant lease payments, from either co-location customers or hyperscalers. Proceeds are typically used to refinance existing debt and expand data-centre capacity.

Against this backdrop, the web of circular financing in 2025 has brought some of the neocloud providers to the fore, offering AI developers access to computing power on a rental basis. The GPU-as-a-Service (GPUaaS) model shifts AI infrastructure spending from upfront capex to flexible operating costs for AI training and inference.

Leading players have recently secured a number of long-term contracts with hyperscalers. Nebius, an Armsterdam-based neocloud company, for example, has signed an agreement with Microsoft to provide GPU services with the total contract value up to $19.4bn through 2031 and a $3bn agreement with Meta over five years. These long-dated contractual obligations would create predictable and stable cash flows, allowing computing power to be securitised in the same way data centre operators issue data centre ABS & CMBS to expand capacity in the competitive GPU-as-a-Service market.

While no high-profile securitisation transactions have yet emerged, the Financial Times reported that some technology bankers have seen ABS deals on AI debt in recent months. Details of these deals remain limited.

Where the securitisation thesis breaks down, for now

That said, the picture has become more mixed in recent months, with early signs of strain emerging across the AI landscape. Often as a canary in the coal mine, equity capital markets have begun to reassess the sustainability of AI-driven investment. Oracle shares have plummeted 43 percent as of December 23, 2025 from their highest level earlier in September when Oracle inked a $300bn computing power deal with OpenAI. In this deal, OpenAI will purchase computing power capacity worth $300bn from Oracle over five years, per the Wall Street Journal. The shift has also been reflected in the derivative markets. Oracle’s five-year credit default swap (CDS) skyrocketed from around 37 basis points in July to 151.3 basis points in November 2025, the highest level since 2009, per Bloomberg.

The web of circular financing in 2025 has brought some of the neocloud providers to the fore

The scale of the market sentiment reflects widespread concern about the feasibility of Oracle’s recent expansion. In its latest 10-Q earnings report, Oracle disclosed $248bn of additional lease commitments, largely tied to the build-out of AI infrastructure.

The main concern around Oracle is twofold, per Bloomberg. First, there is a mismatch between the duration of Oracle’s lease commitments and its contracted revenues. While lease obligations are expected to spread across 15 to 19 years, most of its contracts are due in the next five years, exposing a company at the epicentre of AI infrastructure build-out to renewal risk and potential excess capacity if demand softens. Second, it might under-depreciate its GPUs and need to upgrade their servers in the middle of a lease. It currently depreciate IT equipment over six years as most of its peers do. However, there is no answer as to how long GPUs can last for as ChatGPT was only introduced three years ago on November 30, 2022.

Similar pressure has been evident elsewhere. CoreWeave and Nebius shares have slid 55 percent and 30 percent from their respective peaks as of the end of 2025.

Despite these sharp equity corrections, the broad picture for AI infrastructure funding is still resilient. In an interview with CNBC in December 2025, Sung Cho, co-head of public tech investing and US fundamental equity at Goldman Sachs, however, reinforced confidence in the sustainability of AI funding. He claimed that, viewed in aggregate, 90 percent of the capital expenditure to date in AI is funded by hyperscalers’ operating cash flows with only 10 percent financed by corporate debt, the majority of which is issued by Meta, whose credit ratings are higher than those of the US government.

For computing power ABS and potentially more exotic financing vehicles to emerge at scale, clearer evidence of AI monetisation might be required. In the near term, a viable B2B2C model, where AI adoptions translates directly into productivity boost and margin expansion for end customers, could serve as the first dawn. Once such economics are established, computing power ABS deals might become mainstream, diversifying the spectrum of financing options available to the AI industry.