Over 20 years ago, I sat in a lecture hall while a professor talked excitedly about artificial neural networks (ANNs) and their potential to transform computing as we knew it. If we think of a neuron as a basic processing unit, then creating an artificial network of them would be akin to multiplying processing power by several factors and replacing the traditional view of each computer having one central processing unit, or CPU.

I found the concept of modeling the neurons of the human brain compelling, but frustratingly inaccessible. For one thing: how? How exactly do we translate the firing of neurons, a complex electro-chemical event that is not yet fully understood, and apply it to computing? This is before we even get into neural communication, the coordinated activity of neural networks and the even more complex questions surrounding consciousness. How exactly do we get computers to ‘think’ in the same way that we do? Back then, I had a laptop that was an inch thick and capable of a relatively limited number of tasks. It seemed almost unfathomable to think that these ideas could be put into practice alongside the current incarnation of silicon-based chips.

It would take 10 years before a research paper from Google changed everything. In 2017, a team of researchers at Google published a paper with an unassuming title: Attention Is All You Need. Few could have predicted that this work would mark the beginning of a new epoch in artificial intelligence. The paper introduced the ‘transformer’ architecture – a design that allowed machines to learn patterns in language with unprecedented efficiency and scale. Within a few years, this idea would evolve into large language models (LLMs), the type of which was popularised by OpenAI’s ChatGPT. It was the foundation of systems capable of reasoning, translating, coding and conversing with near-human fluency. But this was not the first step.

The cost of developing AI is, by any measure, extraordinary

A year earlier, Google’s Exploring the Limits of Language Modeling had shown that scaling artificial neural networks – in data, parameters and computation – yielded a predictable, steady rise in performance. Together, these two insights – scale and architecture – set the stage for the era of generative AI. Today, these models underpin nearly every frontier of AI research. Yet their emergence has also brought about a deeper question: could systems like these, or others inspired by the human brain, lead us to artificial general intelligence (AGI) – machines that learn and reason across domains as flexibly as we do?

There are now two distinct paths of research for AGI. The first are LLMs – trained on huge amounts of text through self-supervised learning, they display strikingly broad competence in several key areas: reasoning, coding, translation and creative writing. The suggestion here – and a giant leap from lecture hall discussions about ANNs – is that generality can emerge from scale and architecture.

Yet the intelligence of LLMs remains disembodied. They lack grounding in the physical world, persistent memory, and self-directed goals. And this is one of the central philosophical arguments that hampers the legitimacy of this path for AGI. Our ability to learn is arguably grounded in experience, our ability to perceive the world we live in and actively learn from it. If AGI ever arises from this lineage, it may not be through language models alone, but through systems that combine their linguistic fluency with perception, embodiment, and continual learning.

The other path

If LLMs represent the abstraction of intelligence, whole brain emulation (WBE) is its reconstruction. The concept – articulated most clearly by Anders Sandberg and Nick Bostrom in their 2008 paper Whole Brain Emulation, A roadmap – envisions creating a one-to-one computational model of the human brain. The paper describes WBE as “the logical endpoint of computational neuroscience’s attempts to accurately model neurons and brain systems.” The process, in theory, would involve three stages: scanning the brain at nanometre resolution, converting its structure into a neural simulation, and running that model on a powerful computer.

If successful, the result would not merely be artificial intelligence – it would be a continuation of a person, perhaps with all their memories, preferences, and identity intact. WBE, in this sense, aims not to imitate the brain but to instantiate it.

Running from 2013 to 2023, a large-scale European research initiative called the Human Brain Project (HBP) aimed to further our understanding of the brain through computational neuroscience. AI was not part of the initial proposal for the project, but early successes with neural net deep learning inarguably contributed to its inclusion.

A year before the project started, in what is often referred to as the ‘Big Bang’ of AI, the development of an image recognition neural network called AlexNet rewrote the book on deep learning. Leveraging a large image dataset and the parallel processing power of GPUs was what enabled researchers at the University of Toronto to train AlexNet to identify objects from images.

As the 10-year assessment report for the HBP concludes, researchers realised that “deep learning techniques in artificial neural networks could be systematically developed, but they often involve elements that do not mirror biological processes. In the last phase, HBP researchers worked towards bridging this gap.” It is this, the mirroring of biological processes, which the patternist philosophy wrestles with. It is the idea that things such as consciousness and identity are ‘substrate independent,’ and are held in patterns that could successfully be emulated by a computer.

As Sandberg and Bostrom noted, “if electrophysiological models are enough, full human brain emulations should be possible before mid-century.” Whether realistic or not, this remains one of the few truly bottom-up approaches to AGI – one that attempts to build not a model of the mind, but a mind itself.

It is perhaps no surprise that LLMs have taken off when WBE still seems to be in the realm of science fiction. It is undoubtedly a harder sell for investors, no matter how alluring to egocentric billionaire types the idea of being able to copy yourself may be.

The price of intelligence

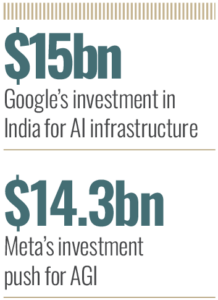

The cost of developing AI is, by any measure, extraordinary. The Wall Street Journal recently reported that Google will invest $15bn in India for AI infrastructure over the next five years. The Associated Press indicated that Meta has struck a deal with AI company Scale and will invest $14.3bn to satisfy CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s “increasing focus on the abstract idea of ‘superintelligence’” – in other words, a direct pivot towards AGI.

These are big numbers, especially considering that the EU awarded Henry Markram, co-director of the HBP, just €1bn to run his 10-year mission to build a working model of the human brain. Beyond corporate announcements, research institute Epoch AI reports that “spending on training large-scale ML (machine learning) models is growing at a rate of 2.4x per year” and research by market data platform Pitchbook shows that in 2024 investment in generative AI leapt up 92 percent year-on-year, to $56bn.

For investors, the risk profile of AGI research is, to put it mildly, aggressive. The potential ROI depends not only on breakthroughs in model efficiency, but also on entirely new paradigms – memory architectures, neuromorphic chips and multimodal learning systems that bring context and continuity to AI.

Bridging two hemispheres

Large language models and whole brain emulation represent two very different roads towards the same destination: general intelligence. To my mind, it seems that neither one can do it alone. LLMs take a top-down path, abstracting cognition from the patterns of language and behaviour, discovering intelligence through scale and statistical structure. WBE, by contrast, is bottom-up. It seeks to replicate the biological mechanisms from which consciousness arises. One treats intelligence as an emergent property of computation; the other, as a physical process to be copied in full fidelity.

Yet these approaches may ultimately converge, as advances in neuroscience inform machine learning architectures, and synthetic models of reasoning inspire new ways to decode the living brain. The quest for AGI may thus end where both paths meet: in the unification of engineered and embodied mind.

Spending on training large-scale machine learning models is growing at a rate of 2.4x per year

In attempting to answer what makes a mind work, we find that the pursuit of AGI is, at its heart, a form of introspection. If the patternists are right and the mind is substrate-independent, a reproducible pattern rather than a biological phenomenon, then its replication in silicon will profoundly alter how we view the ‘self’ if we ever do replicate the mind in a machine. That said, if the endpoint of humanity is being digitally inserted into a Teslabot to serve out eternity fetching a Diet Coke for the likes of Elon Musk, then it might be more prudent to advise restraint.

Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia believes that “artificial intelligence will be the most transformative technology of the 21st century. It will affect every industry and aspect of our lives.” Of course, as the man leading the world’s foremost supplier of AI compute chips, he has a vested interest in making such statements.

Perhaps it is best then, to temper such optimism and leave you with the late Stephen Hawking’s warning: “success in creating AI would be the biggest event in human history. Unfortunately, it might also be the last, unless we learn how to avoid the risks.”