There is a stereotype about Chinese students that has taken root in the West. It says that they are industrious, hard-working and, most significantly, smart. It’s one of the reasons China is expected to dominate the hi-tech industries of the future, like artificial intelligence, biotech and interplanetary travel. But this stereotype masks a more complicated picture of educational attainment in the country.

Unsurprisingly, the most populous country in the world is one of huge contrasts. While China’s major cities are certainly full of successful businesses and high-ranking universities, a look at its rural areas paints a very different picture. China remains one of the most unequal countries in the world – a fact that is masked by its economic rise. According to the 2020 Hurun Global Rich List, China now has more billionaires than the US, but only 63.7 percent of China’s rural population has regular access to reliable sanitation facilities. If you count migrant workers living in cities, as much as 99 percent of the country’s impoverished population either comes from or still lives in rural areas.

These statistics should not only shock the Chinese Government from a human point of view, but they should serve as an economic warning as well. If China is to continue its spectacular economic ascent, it will need to focus on its human capital. The levels of education in the country must be improved if China is to transition from a manufacturing-based economy to a highly skilled, service-based one. For that to happen, it will need the help of all of its citizens, not just those living in cities.

Room for improvement

No one could accuse China of not taking education seriously. The country’s school system, which requires pupils to complete nine years of attendance – six at primary school and three at a secondary institution – is the largest state-run education system in the world. President Xi Jinping has long understood that China will not be able to compete with the developed world economically or technologically without building on its recent educational improvements. “The competition for comprehensive national strength is essentially a competition for talent,” Xi explained at a Beijing symposium in 2016. “We need to accelerate development of a globally competitive talent system, bring together the best available talent, and put it to use.”

The levels of education in the country must be improved if China is to transition from a manufacturing-based economy to a highly skilled, service-based one

Families in China appear keen to support the country’s efforts to strengthen its human capital. Annual per capita expenditure on educational, cultural and recreational services among urban private households rose from CNY 669.58 ($94.47) in 1990 to CNY 2,974.1 ($419.60) in 2018. Aside from the bragging rights that come with having high-achieving offspring, the connection between a strong education sector and economic performance is well established.

A 2003 study conducted by Philip Stevens and Martin Weale for the National Institute of Economic and Social Research found a clear correlation between the strength of a country’s education sector and its economic power, with a one percent increase in primary school enrolment leading to a GDP boost of 0.35 percent. Even a country that enrols 100 percent of its children at school would be foolish to rest on its laurels; school performance can always be improved, and a constant refreshing of curricula is necessary.

In China, it’s evident that educational and economic developments have reinforced one another. Since the era of Deng Xiaoping, who led the People’s Republic of China at the end of the 20th century, education has taken on an increasingly important role. “Economic construction, social development, and scientific and technological progress all depend on the intellectual development of the Chinese nation, an increased number of trained personnel, and further growth of education based on economic development,” read the guidelines for China’s Seventh Five-Year Plan. “During the period of the plan, we must attach as much importance to education as we do to economic development and orientating our work to the needs of modernisation, the world and the future, [and] strive to bring about a new situation in education.”

In contrast to the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76, when members of the intelligentsia were the subject of suspicion, Deng’s era and the decades that followed have witnessed significant improvements in educational attainment. For example, since 1982, the country’s adult literacy rate has skyrocketed from 65.5 percent to 96.8 percent (see Fig 1).

But education is not just beneficial on a personal level; it is vital if individuals are to both contribute to and benefit from societal advancements. It is no surprise, then, that China’s economic rise has coincided with its educational one.

A broken system

Improvements to the education system in China have not been implemented uniformly. Urbanisation has occurred at a rapid rate in the country – in 1978, just 17.92 percent of the population lived in urban areas, but by 2018, this figure had risen to 59.58 percent. And while this trend has helped to transform some of China’s cities into centres of innovation and corporate success, it has left many rural areas neglected.

Because of its failure to ensure that rural and urban areas keep pace with one another educationally, China, on the whole, remains behind its peers in terms of development. In 2015, the high school attainment rate for middle-income countries, of which China counts itself, was 36 percent, far below the average of 78 percent seen in high-income countries. China’s figure, however, is just 30 percent, behind some less-well-off states like Indonesia.

While there has been a substantial improvement in school attendance in rural areas, concerns remain about the quality of education being received outside the country’s urban conurbations. Most of the expansion can be attributed to the growth of vocational education and training schools, but the quality of schooling appears mixed at best.

Some of the problems facing China’s young people in rural areas cannot be pinned on the formal education system, however. Rates of developmental delay among infants and toddlers were found to be high in China’s rural areas, and social-emotional delays were similarly troubling. A recent study using the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development found that 58 percent of infants and toddlers in China showed delayed social-emotional skills. Language delays, anaemia, poor vision and other health problems were also observed.

Aside from educational failings, rural China remains beset by poverty, poor infrastructure and a lack of social support outside of the family unit. As of the end of 2017, the incidence of poverty in 167,000 villages exceeded 20 percent, several times higher than the national poverty rate of 3.1 percent. In fact, by some metrics, the plight of China’s rural citizens is getting worse: in 2019, rural per capita income actually fell if migrant workers were removed from the data.

“Easing poverty has always been one of the Chinese Communist Party’s priorities, as high and unsustainable levels of poverty could threaten social stability and therefore undermine the legitimacy of China’s single party,” Ricard Torné, Head of Economic Research at forecasting firm FocusEconomics, told Forbes in 2018. “Boosting government-subsidised homes for rural dwellers, promoting economic activity outside urban areas and increasing loans to low-income people will top [Xi’s] agenda on poverty reduction.”

Cultural issues are also holding the country back. China operates a domicile registration system, known as the hukou system, that determines the social services that any family can access in their town, village or city of residence. The two types of hukou – rural and urban – exacerbate China’s education divide. Holders of rural hukou, although they may have moved to the city (perhaps travelling with their family in search of better employment opportunities), will face difficulties accessing education in their new surroundings.

For example, only around 30 percent of migrant children living in Shenzhen and Beijing attend state schools; the rest are sent to private institutions or returned to their original place of hukou registration. These hurdles remain prevalent all the way up the education pyramid: between 2009 and 2014, 97 percent of China’s poorest counties sent no students to Beijing’s Tsinghua University, widely regarded as the country’s premier educational institution.

Putting in the work

It must be said that the Chinese Government has not sat idly by and watched while its cities accelerate away from its rural areas. According to the country’s Ministry of Education, 83 percent of rural households achieved some form of high school attainment in 2015, an increase of 40 percent compared with 2005.

The Notice of the State Council on Deepening the Reform of Funds for Rural Compulsory Education was issued at the end of 2005, comprising a new compulsory education system for rural areas. It made it mandatory for local and national governments to share educational expenses on rural compulsory education, and committed to increasing investment incrementally. Other policies, like the 2010 Transformation Plan for Underdeveloped Rural Compulsory Education Schools and the Plan for Improving the Nutrition of Rural Students Receiving Compulsory Education have also helped improve the situation in many rural areas.

Charitable organisations, such as the Rural Education Action Programme (REAP), are also stepping in to patch up governmental failures. REAP found that Beijing’s National Teacher Training Programme, an initiative that has been running since 2010, has had no impact on teacher performance. As such, REAP is now looking at new approaches for teacher training in rural areas: for example, it has partnered with the University of Chicago and school districts in China to develop a more effective incentive programme to boost outcomes.

Overall, it appears that China does recognise its educational development in rural areas is not good enough. Since 2006, around 335,000 college graduates have been placed in rural schools in Central and Western China. Computers have been purchased and investment has increased. But there remains much catching up to do if both urban and rural children are to have access to equal opportunities.

Locked down and shut out

If the situation for China’s rural children was difficult before the spread of COVID-19, it has since become a lot worse. The pandemic has thrown the country’s education divide into stark relief. When Beijing shut schools in late January to slow the spread of the disease, wealthy families living in China’s gleaming cities coped well enough. In small towns and villages, where online infrastructure is lacking, many children simply had to go without schooling altogether. In Guangxi, one of the country’s poorer provinces, some secondary schools had to abandon online classes after many pupils were unable to log in.

As recently as 2018, between 56 and 80 million Chinese citizens said they did not have access to an internet connection or online-enabled device. Many families have just one smartphone between them, which means making it available for online lessons is not always practical. Although the official line from the Chinese Government is that 98 percent of the villages classified as ‘extremely poor’ have broadband coverage, research conducted by the China Development Foundation puts the figure at just 44 percent.

It must be noted that some institutions are coping with these new pressures. Zhejiang University, located in the province of the same name, was able to offer more than 5,000 of its courses online by early March. The university also offered training sessions for its 3,670 faculty members to ensure that staff had the digital skills required to enable remote learning. Additional funding has been allocated to some of the most disadvantaged students.

However, many of the most pressing education issues related to COVID-19 concern school-age children, not university students. A study conducted by the International Food Policy Research Institute found that 79 percent of those living in villages reported a negative impact on local children’s education. Economic effects have also become evident: REAP found that 31 percent of families reported that having children at home during the lockdown meant they could no longer go to work.

There has been lots of talk about creating a ‘new normal’ in the post-COVID-19 world. For China’s rural areas, this must involve renewed investment in technological infrastructure to ensure that, should a similar disruption occur in the future, the country’s educational divide does not widen further.

Techy teachers

Technology has long been viewed as a way of improving education. With the spread of COVID-19, it has suddenly become an essential tool for keeping students and teachers connected. Here is a selection of China’s pioneers in educational technology.

17zuoye

Widely regarded as the largest online education platform in China, 17zuoye, which translates to ‘homework together’ in English, serves more than 120,000 schools in the country. Founded in 2011, the company provides a bespoke learning strategy for each student by using big data and artificial intelligence. The firm has attracted significant investor interest

and had some success in terms of monetisation, using intelligent supplementary textbooks and livestream tutoring.

VIPKid

Pairing tutors from the US and Canada with Chinese students between the ages of four and 15 looking to improve their English, VIPKid has achieved huge success since it was founded in 2013. Despite some concerns last year over rising costs, the company has still managed to achieve a valuation in excess of $4bn. Starting as a desktop program, VIPKid now also boasts a mobile app that enables students to access upcoming tutoring schedules and view teacher feedback.

Makeblock

Founded in Shenzhen in 2013, Makeblock aims to achieve the deep integration of technology and education by using hardware, software, content solutions and robotics. Already, the company has sold its products – including educational resources, like the company’s do-it-yourself robotics kits – to more than eight million users across 140 countries. Makeblock’s reputation has grown so rapidly that it is already viewed as a worldwide leader in STEAM (science, technology, education, arts and mathematics) solutions.

Held back a year

If China is to continue its economic development, it will need to do more than simply point in the direction of its multinational companies – the likes of Alibaba, Tencent and Huawei. It will need to address the issues affecting those that live far from the bright lights of Beijing and Shanghai. Stanford economist Scott Rozelle has found that for countries to make the transition from middle to upper-income status, at least 75 percent of its working-age population needs to have completed high school – a statistic China is yet to achieve.

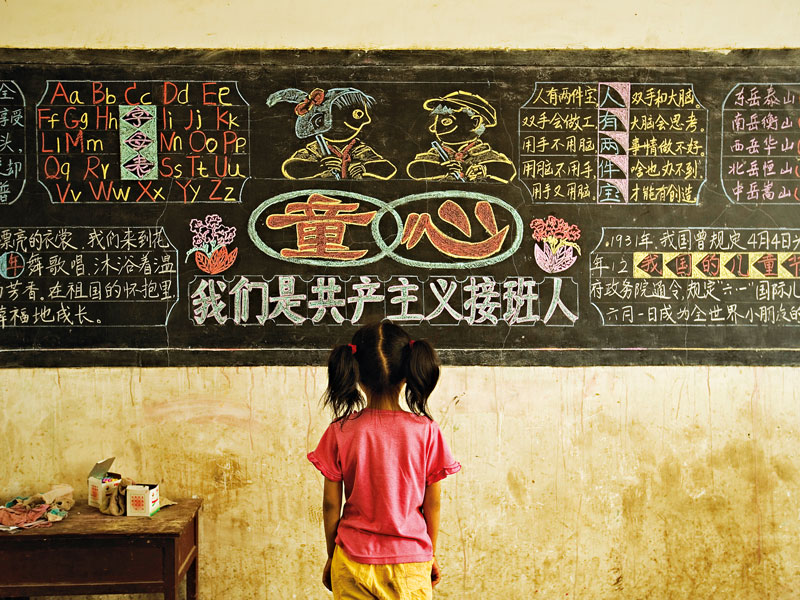

The image of the Chinese whizz-kid acing maths and science is good for the Communist Party’s image, but it’s not entirely accurate. In 2015, when results from the Programme for International Student Assessment tests were extended to include students from outside Shanghai, China’s rankings fell significantly. More money will need to be injected into rural education and the hukou system may have to be abandoned if Beijing wants to clear the way for more of its citizens to make the transition to urban life. Culturally, the Communist Party will also have to make some compromises. Lessons in ideological conformity may help maintain discipline in a one-party state, but indoctrination can lead to rigidity of thought. Xi’s beliefs, now enshrined in the state’s constitution, may be important, but they are not as important as science and maths for the country’s continued economic development.

In addition to China’s focus on economic success, Xi believes he can eradicate poverty in the country by the end of this year. On top of this, by 2049, the aim is for China to be the world’s top international education destination. It will take a country-wide effort to achieve any of these goals. China has always held lofty ambitions, but in its villages and towns, it is in serious danger of falling short of them.