For such a venerable and pioneering financial institution, it is somewhat surprising that insurance market Lloyd’s of London is still looked at with considerable suspicion by many within the global business community. Despite a long and successful history, the scandals that hit towards the end of the 1980s – and the ensuing losses of colossal proportions to policyholders – have meant that Lloyd’s has struggled to recapture the lustre that it once held.

However, perhaps now is time that global investors, and particularly those in the US, look at Lloyds with renewed interest. A marketplace known for insuring almost anything has undergone the necessary reforms to ensure that policyholders are suitably protected, but also allows for the sorts of returns and investments not possible elsewhere.

Not many of the world’s most prestigious financial institutions can claim to emerge from such humble beginnings as a coffee shop, but that is exactly where the world’s oldest insurance market first developed in London. In 1688, in the back rooms of Lloyd’s Coffee House, a market formed that would dominate the insurance world for centuries.

Originally focused on the shipping industry, with merchant ships being insured by many of the coffee house’s customers. It moved from Lloyd’s Coffee House to new premises at the Royal Exchange on Cornhill in 1774, where it perfected the art of people pooling – and therefore spreading – risk, and subsequently became the primary place for insuring against all sorts of events.

Defining the structure

Lloyd’s is in a unique position in that it is not itself a corporation, but instead considered a market by UK law. Lloyd’s itself does not underwrite policies, but it acts as the market where individual market makers known as ‘Names’ offer to underwrite many types of policy, offering unlimited liability, meaning their entire wealth could be seized in the event of a claim.

‘Names’ are essentially the underwriters at Lloyd’s, and can include internal Lloyd’s members and external investors. General insurance and reinsurance are covered at Lloyd’s, with underwriters coming together to form syndicate funds that then offer policies to clients. Investing in a syndicate at Lloyd’s is unlike buying a normal security. Instead, investors are made Members of the syndicate for a one-year period, known as the ‘Lloyd’s Annual Venture’, and the syndicate would then be dissolved at the end of that period.

Lloyd’s of London timeline

1688

Humble beginnings in the back of Lloyd’s Coffee House

1774

Moves to new premises at Royal Exchange on Cornhill

1871

Lloyd’s Act passed into government

1980s

Scandal swirls among accusations of fraud and incompetence

2000s

Reputation repair: Lloyd’s starts to make a comeback

The syndicate is then re-formed the next year, often having the same members as before. The Council of Lloyd’s manages the market, which is responsible for supervising the activities going on. These activities are made up of two distinct groups: the Members that provide capital and insurance agents or brokers that underwrite the risks and act on behalf of the Members.

Known for taking on pretty much any insurance policy, a vast number of bizarre things have been secured through the Lloyd’s market. These have included world-famous food critic Egon Ronay insuring his taste buds for $400,000 in 1957.

This was surpassed in 2009 when Costa Coffee took out a £10m policy against the prospect of their chief coffee taster, Gennaro Pelliccia, losing his sense of taste. 20th Century Fox insured actress Betty Grable’s legs for $1m each in the 1940s due to her huge popularity, while Australian cricketer Merv Hughes insured his trademark moustache for $370,000. Perhaps one of the highest profile policies was the one Irish dancer Michael Flatley took out for his legs in 2000, worth a staggering $47m.

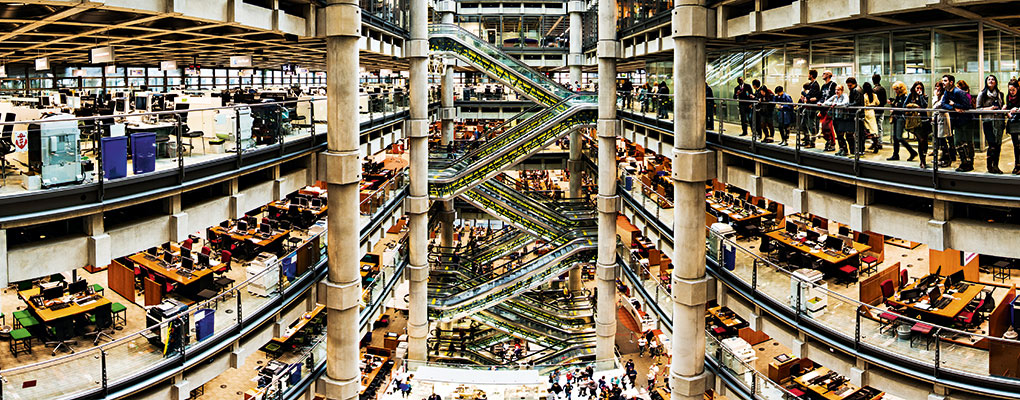

With its iconic building, Lloyd’s also forms a distinct part of London’s Square Mile. Designed in the late 1970s by architect Richard Rogers, it is notable for looking as though it has been constructed inside out, with lifts and ducts found on the exterior of the building. Finished in 1986, the Lloyd’s building signified the dominance of the market during that period, but perhaps also represents the extravagance of the period.

Beginning of the trouble

Lloyd’s was formerly recognised in British law after the 1871 Lloyd’s Act, while the subsequent 1911 Act clarified the market’s objectives, which were to promote the interests of members and provide market information. By the 1970s, concerns arose around the tax structure of the UK’s financial markets, resulting in sweeping reforms to many sectors.

Lloyd’s was affected by the increase of earned income tax to 83 percent, resulting in syndicates preferring to make small underwriting losses in return for larger investment profits. Syndicates also began moving offshore, creating a situation that would later cause a great deal of controversy. At the start of the 1980s, Lloyd’s governing Council undertook plans to overhaul its regulatory framework, which would then become the Lloyd’s Act of 1982.

Lloyd’s of London still carries a negative reputation in the US, where many investors were badly burnt by their experiences of before

Designed to give the external Names, who were not involved on a day-to-day basis at Lloyd’s, a greater say in the running of the business, it also saw ownership of the managing agents of the Lloyd’s syndicates separated from the insurance broking firms. The hope was that this would mean an elimination of conflicts of interest between the syndicates and the brokers.

The reputation and integrity of Lloyd’s took a catastrophic hit in the 1980s as a result of the asbestos scandal. In the US, surprisingly large settlements on asbestos and pollution (APH) policies led to huge claims. A number of US states accused Lloyd’s of large-scale fraud, particularly the apparent withholding of knowledge regarding the level of asbestos and pollution claims. Lloyd’s was accused of encouraging investors to take on liabilities even though the market knew that colossal claims dating back decades were being made.

US regulators subsequently charged Lloyd’s and its associates with fraud and the selling of unregistered securities. This included Ian Posgate, one of Lloyd’s leading underwriters, who was charged with taking money from investors as part of a clandestine plan to buy a Swiss bank; a charge he was later acquitted of.

The asbestos claims were hard to predict because they affected workers many decades before. For example, a factory worker from the 1960s that was exposed to asbestos may have only developed health issues decades later, resulting in his suing his employer for compensation. The employer would then claim for insurance on a policy drawn up twenty years beforehand, before the real risks associated with asbestos were known. The ultimate result was the bankruptcy of thousands of investors in Lloyd’s syndicates as a result of the unforeseen risks.

Archaic accounting

As syndicates last a year and were accounted for separately, despite their continuing nature, there would be numerous separate incarnations of the syndicate. Liabilities could be carried over each year because of the way profits and losses were accounted, resulting in current syndicate members having to pick up the bill for policies written many years previously. Many holders felt this was an unfair system and had not been properly explained before investing.

Perhaps one of the most controversial factors of the scandal is the policy dubbed ‘recruit to dilute’, where some Lloyd’s officials were said to have deliberately sought new Names in advance of the forthcoming asbestos claims. This was reportedly done in the full knowledge that there was an impending wave of claims over asbestos. In the subsequent court cases over the losses, claims of ‘recruit to dilute’ were rejected, although the judge said that the Names at Lloyd’s that had lost their money were “the innocent victims… of staggering incompetence.”

As the world continues to experience ever-more uncertain political and environmental events, an insurance market such as Lloyd’s is the perfect place to secure against the worst possible outcomes

The result of all these issues was that many Names that were exposed to the asbestos claims lost vast sums of money, and in many cases were declared bankrupt as a result of the unlimited liability of the policies. In the aftermath, new Names at Lloyd’s that joined after 1994 did so with limited liability. Financial requirements for underwriting were also reformed, with checks made to ensure there were enough liquid assets available to back any losses.

Obviously acting as an insurance underwriter will always carry a good deal of risk, but the policies employed by many at Lloyd’s during this period clearly didn’t offer the necessary protections to those they had signed up.

While Lloyd’s has rebounded since its catastrophic period in the early 1990s, it has begun to face increased competition from newer markets elsewhere. However, the flexibility offered at Lloyd’s puts it in a unique position, with all manner of eventualities being offered for insurance. As the world continues to experience ever-more uncertain political and environmental events, an insurance market such as Lloyd’s is the perfect place to secure against the worst possible outcomes.

Lloyd’s of London still carries a negative reputation in the US, where many investors were badly burnt by their experiences of before. However, in light of the banking crisis that saw the market’s namesake in the UK partly nationalised, Lloyd’s – and insurance in general – is seen as much safer bet than traditional banking investments. A renewed focus on assessing risk has also meant that Lloyd’s is a much more secure place to put money than it was many years ago.

Speaking to the Economist in 2012, Rob Childs, of Lloyd’s syndicate Hiscox, said that attitudes to Lloyd’s had changed over the last 20 years, in contrast to those towards its namesake. “If you were at a dinner party and someone asked where you worked, you’d be happy if people thought Lloyd’s was a bank. Now, 20 years later, it’s the reverse.”

Such an old and experienced marketplace has played an integral part of London’s financial market, as well as helping to develop the global insurance industry that we see today. Tradition still plays an important part in the day-to-day activities at Lloyd’s, with business conducted in person and brokers queuing to do business with underwriters. While it may not be the risky place it once was, there is still the diverse range of insurance activities that the typical insurance houses wouldn’t dream of offering.

Strange items insured by Lloyd’s of London

From Bruce Springsteen to Michael Flatley, Lloyd’s of London really did live up to its reputation of being an ‘insure almost anything’ market. Here are some of the strangest ‘items’ to be covered by one of their policies.

Harvey Lowe’s hands, 1932-1945, $150,000

Betty Grable’s Legs, 1940s, $2m

Ken Dodd’s teeth, 1967-1992, $7.4m

Merv Hughes’ Moustache, 1985-1994

Bruce Springsteen’s voice, 1980s, $6m

Michael Flatley’s legs, 2000-present, $47m