“Sadly, the American Dream is dead”, were the despairing words of Donald Trump as he announced his presidential bid back in July 2015. For all the business mogul’s false claims during the ensuing campaign, this is one that might just ring true.

According to research conducted by the Equality of Opportunity Project, the American Dream is indeed fading, and children can no longer expect to enjoy a higher standard of living than their parents. In 1940, a phenomenal 90 percent of American 30-year-olds earned more money than their parents at the same age. Now, that figure has dropped to just 50 percent (see Fig 1).

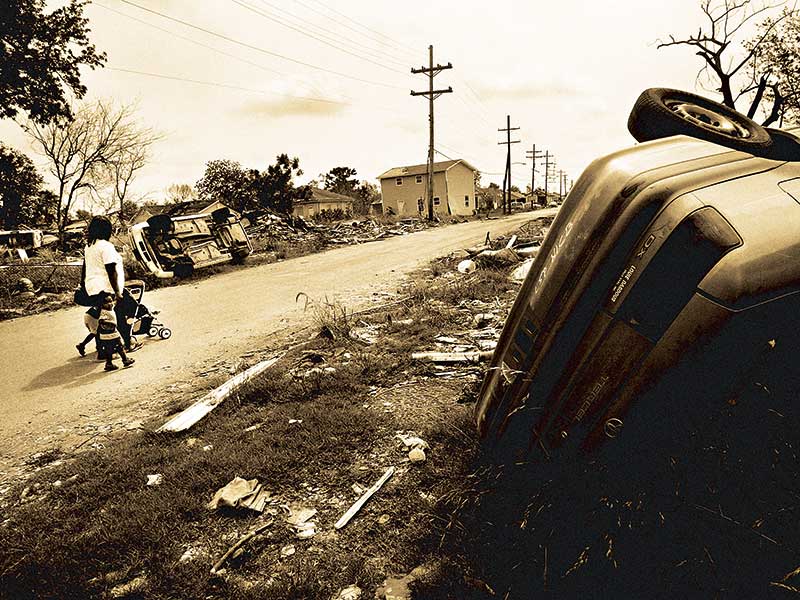

The Great Recession and the Not-So-Great Recovery have had a profound impact on the lives of most Americans, creating new economic hurdles and aggravating the existing challenges of poverty, unemployment and income inequality. While this economic strain has certainly been felt all across the US, its impact is most stark in the American South.

For several decades now, the southern states have been trapped in a cycle of economic and social decline. Four of the five poorest US states are concentrated in the South, with poverty rates soaring across the region. Southern states also have the lowest rates of upward mobility in the country, meaning a child born in the South is less likely to rise out of poverty than if they had been born in a different region of the US.

Overall, around seven percent of American children born in the bottom fifth of income distribution will make it to the top fifth in their lifetime, whereas approximately 13 percent of low-income children will do the same over the border in Canada. In the South, however, decades of acute intergenerational poverty mean children are much less likely to climb up the income ladder, with just four percent of the population moving from the bottom bracket to the top.

According to Benny Goldman, a predoctoral fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research: “If you’re born into one of these disadvantaged families in the south-eastern states, then the chance that you’ll ever reach the top 20 percent when you’re older is very small.” Lagging behind the rest of the US in upward mobility, employment rates and wages, the South is in dire need of an economic miracle.

Manufacturing misfortune

In 1938, as the US struggled to recover from the Great Depression, Franklin D Roosevelt declared the South to be “America’s economic problem number one”. Once a rich and prosperous region, the southern economy was crippled by the Civil War and the lengthy Reconstruction Era, and by the time the Great Depression hit in 1929, the region had fallen behind the rest of the country in terms of household income, wages and job security. This trend continued throughout the 20th century, and today the South remains a profoundly troubled region.

Similarly to the rest of the US, the southern states have seen a steady decline in their manufacturing industries, with thousands of factory workers losing their jobs to automation and cheap Chinese labour. In the South, however, most of these job losses have occurred in the region’s formerly ubiquitous textile industry. In North Carolina, for example, 40 percent of jobs were concentrated in textile and apparel manufacturing in 1940, but by 2013, the industry accounted for just 1.1 percent of the state’s jobs.

Between 1997 and 2009, around 650 textile plants closed in the southern states, leaving thousands of workers without jobs and depressing entire communities (see Fig 2). The blue-collar economic heyday of the 1970s is now long over, but many states have failed to adjust to this new commercial landscape.

While the economic strain of the Great Recession has certainly been felt all across the US, its impact is most stark in the American South

There are stories of manufacturing losses occurring all over the US – particularly in the once-powerful Rust Belt – but the South has been hit by the double whammy of job losses and low median incomes. Southern states have long been hostile to organised labour and unionised work, and five states still have no state minimum wage.

For workers in Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and Tennessee, wages need only comply with the federal minimum of $7.25 an hour and $2.13 for tipped workers, driving a low-wage economy. This culture is particularly alarming for the region’s auto industry workers, who frequently engage in high-risk work for comparatively little financial reward.

While the South has experienced a rapid decline in its textile industry, car manufacturing is now enjoying something of a resurgence throughout Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi. Between 1980 and 2013, the number of auto industry jobs in the South increased by 52 percent, with 26,000 workers employed in the field in Alabama alone. And yet, far from being a welcome manufacturing renaissance, the phenomenon represents a race to the bottom by profit-motivated auto parts suppliers.

Factory workers are expected to work gruelling 12-hour shifts, often for six or seven days a week. Pay is universally low, and little thought is given to worker safety. According to the Bureau of Labour Statistics, southern workers at parts suppliers earn just 70 cents for every dollar earned by their Michigan-based counterparts. Safety violations are all too common, often resulting in serious injury. In 2015, the chances of losing a limb or finger in an Alabama parts factory was 50 percent higher than the national average risk for the industry.

These jobs may provide a way to escape the demoralising cycle of unemployment, but low-wage, high-risk industries aren’t the answer to the South’s economic woes.

Separate and unequal

Joblessness and depressed wages do indeed lead to low family incomes, but economic decline is not solely to blame for the South’s alarming poverty rates. Interestingly, when examining upward mobility in the US, the Equality of Opportunity Project observed a correlation between low mobility and areas of concentrated racial segregation.

“Segregation along many different fronts appears to be related to upward mobility rates – with the strongest correlation being racial segregation”, said Goldman. “In places where there is less racial segregation, this seems to help children to climb the income ladder.”

Newly released census data shows that black-white segregation is in modest decline across America, but still remains high in most large US cities. Some 50 years after the end of legally enforced segregation, black and white Americans still often inhabit vastly different neighbourhoods, with African Americans more likely to live in areas of concentrated poverty. While the nation’s decades-old discriminatory housing policies are certainly somewhat to blame for the current state of residential segregation, the phenomenon has been further aggravated by instances of ‘white flight’ from the inner cities to the suburbs, and the use of excusatory redlining practices.

According to a report by the Pew Research Centre, in 2014 the median household income for black Americans was just $43,300, compared with $71,300 for white Americans. As such, African Americans are often priced out of the more affluent, majority-white suburbs, and are therefore denied access to the same public services.

“In the United States, school funding is largely done via property taxes”, Goldman explained. “So if you have an area that’s very wealthy, with high property taxes, then that school is going to be well funded.” Of course, the inverse is true for low-income neighbourhoods: tying school funding to property taxes means children from the poorest families will most likely attend underperforming schools, further entangling them in a vicious cycle of poverty.

Southern states have long been hostile to organised labour and unionised work, and five states still have no state minimum wage

According to Ted Ownby, Director of the Centre for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi: “Today, we’re seeing a very different type of racial segregation… It’s not based on laws and rules as it was in the past, but it certainly has to do with zoning, educational access and economic access, and it has strong connections to the issue of race.”

Racial segregation remains a crucial issue in cities throughout the nation, but is perhaps felt most keenly in the South. Between 1970 and 2010, segregation levels increased in just six metropolitan areas across the US, but five of these (Birmingham, Chattanooga, Gadsden, Mobile and Monroe) were located in the southern states. The social segregation of the Jim Crow era might be long over, but modern residential segregation has become a poverty trap for many southern African Americans.

Incarceration at a cost

When examining the causes of economic decline and spikes in poverty in the US, many social scientists have begun to point to one key factor: mass incarceration. With a 500 percent increase in the number of imprisoned people between 1985 and 2015, the US is by far the world leader in incarceration. Aside from the ethical implications this phenomenon presents, large scale imprisonment also has a profound impact on the economy.

The 2.2 million people currently behind bars in the US are unable to contribute to society through work, and stand a poor chance of finding gainful employment once released. Meanwhile, it costs taxpayers approximately $31,286 per year to house one inmate in a state prison, putting a significant drain on valuable state resources.

“The prisons system takes an extraordinarily large number of people – especially African American men – and pulls them out of the potential workforce”, said Ownby. “It has such a dreadful set of consequences for the whole society, with economic, personal and family-related implications. People’s lives are essentially taken away, and they are turned into non-citizens, non-voters and non-contributors to the economy.”

When it comes to mass incarceration, the US’ southern states are some of the most punitive. Louisiana has the highest rate of incarceration in the country, with a staggering 776 people imprisoned for every 100,000 citizens. Similarly, the states of Alabama, Mississippi and Georgia all have incarceration rates well above the national average, and also have some of the US’ harshest felony voting laws. All of the southern states employ the death penalty, yet despite the ‘tough on crime’ legislation of the past four decades, longer sentences and high incarceration rates have not played an effective role in reducing crime and recidivism. Indeed, despite having an incarceration rate 13 times higher than that of China, Louisiana still has one of the US’ highest rates of violent crimes.

Instead of tackling crime, mass incarceration has proved counterproductive and costly, taking a significant toll on already stretched southern state budgets. According to the US Department of Education, over the past three decades, state spending on prisons has increased at triple the rate of funding for education, leaving public schools underfunded and underperforming. Louisiana’s budget deficit is expected to reach $313m in 2017, prompting a fresh wave of cuts to higher education and healthcare, while the state attempts to maintain its spending on corrections.

“For far too long, systems in this country have continued to perpetuate inequality”, said then-US Secretary of Education John B King Jr in 2016. “We must choose to make more investments in our children’s future. We need to invest more in schools, not prisons.”

Diseases of despair

The prisons system isn’t the only thing tearing families apart in the US South. Over the course of the past two decades, the misuse and abuse of opioid medications has become a public health crisis, now claiming more than 33,000 lives each year. The opioid epidemic has been called the worst health crisis in US history, with more deaths caused by opioid overdose today than from HIV/AIDS at the peak of the pandemic in the 1990s.

The opioid crisis is now a nationwide epidemic, though the southern states consistently issue the largest number of painkiller prescriptions: in Alabama and Tennessee, there are approximately 143 opioid prescriptions for every 100 people. Just like other so-called ‘diseases of despair’ (heavy drinking, drug addiction and obesity) opioid abuse is most common in areas of extreme poverty.

According to Goldman: “When you look at the southern states, where you have some strong pockets of abject intergenerational poverty, then it’s perhaps unsurprising that those are the areas where crises like these tend to pop up.” Indeed, the Equality of Opportunity Project has used big data to measure the impact of income on average life expectancy, and has discovered that the richest American men can expect to live 15 years longer than the poorest, while the richest American women tend to live 10 years longer than women on the opposite end of the income scale. While it may not entirely explain this discrepancy in life expectancy between the nation’s rich and poor, the spike in deaths from diseases of despair and opioid overdoses could be a contributing factor behind the lower life expectancies of impoverished Americans.

What’s more, while southern Americans are more likely to suffer from chronic illnesses and general ill health, they are also less likely to receive health insurance than if they lived elsewhere in the country. Millions of southerners are currently eligible for coverage under Medicaid, but many states are yet to adopt the healthcare programme. Without adequate insurance policies in place, ill health can have a severely destabilising effect on families already struggling to make ends meet.

The South rising

“I think most of us dwell too long on the causes of the South’s difficulties and too briefly on what is to be done about them”, said Franklin D Roosevelt advisor Harry Hopkins during a nationwide address in 1938. The region might have been President Roosevelt’s “economic problem number one”, but he wasn’t prepared to give up on the once-prosperous South. Now, nearly 80 years on, it is more crucial than ever that the US finds a solution to the South’s economic decline.

4 out of 5

of the poorest US states are located in the South

650

textile plants closed in the southern states between 1997 and 2009

52%

The increase in the number of auto industry jobs in the South between 1980 and 2013

776

people are imprisoned for every 100,000 citizens in Louisiana – the highest rate in the US

The southern states have a host of socioeconomic hurdles to overcome, but there are certainly some bright spots in the region’s future. For some time now, mayors and governors have been looking to attract tech companies and workers to the area, and their efforts are now beginning to pay off. The city of Huntsville, Alabama has become something of a southern tech hub in recent years, with science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) workers accounting for a remarkable 16.6 percent of the workforce.

Atlanta boasts more than 166,690 hi-tech workers, while Chattanooga has invested in superfast internet in order to lure tech companies to Tennessee. With these STEM workers earning good salaries, the hope is that this money will quickly pour back into the local economies, providing much needed support to public schools, health services and businesses.

Aside from these flourishing tech communities, the South also stands to benefit from a renewed interest in the region’s historic and contemporary culture. “Cultural tourism presents something of an economic opportunity for the South”, said Ownby. “Different pockets of the American South have things to offer that the rest of the world is interested in, such as Appalachian life, for example, or country music or the stories of the civil rights movement.”

Moulded by a unique history and boasting a strong regional identity, the South has long exerted an influence over American popular culture. Now southern states are beginning to ask themselves how their local communities might be able to benefit from the lure of the South, and how to best promote cultural tourism as an attractive industry.

Goldman explained: “It’s not as if the American Dream is dead across the board – there’s some places that are doing very well and others that are doing very poorly.” Indeed, while the South might be struggling to boost upward mobility, the good news is that, across the US, there are some areas that are performing strongly. If social scientists can identify what makes cities such as Minneapolis and San Jose so good at propelling low-income children up the income ladder, then this can be applied to social planning strategies elsewhere.

From joblessness to diseases of despair, the South has a long list of economic woes to contend with. And yet the region has shown remarkable resilience and adaptability in the face of adversity. As local governments turn their attention to courting new industries and encouraging economic diversity, the southern states are beginning to dip their toes into much-needed new revenue streams. The American Dream might be fading, but the South is intent on keeping it alive.