On September 15 1992, the British Chancellor Norman Lamont met with Robin Leigh-Pemberton, the then governor of the Bank of England. The Friday before, on September 9, currency speculation had forced the Italian lira to devalue. As a consequence, Britain was facing the same prospect, putting the European Exchange Rate Mechanism under increasing strain. The two men agreed that they would defend the value of the pound through aggressive action, by buying up the sterling of foreign currency exchange markets.

However, as the end of the meeting neared, news came through that Helmut Schlesinger, the head of the German Bundesbank, had told The Wall Street Journal and the German newspaper Handelsblatt that there would have to be a realignment of currency values within Europe’s exchange rate mechanism. As part of the mechanism, Britain’s currency was supposed to shadow Germany’s. Such a statement, just as the UK was attempting to stave off currency devaluation, was not welcome news. “Schlesinger’s remark was tantamount to calling for the pound to devalue”, Sebastian Mallaby noted in More Money than God, his 2010 book about the history of hedge funds.

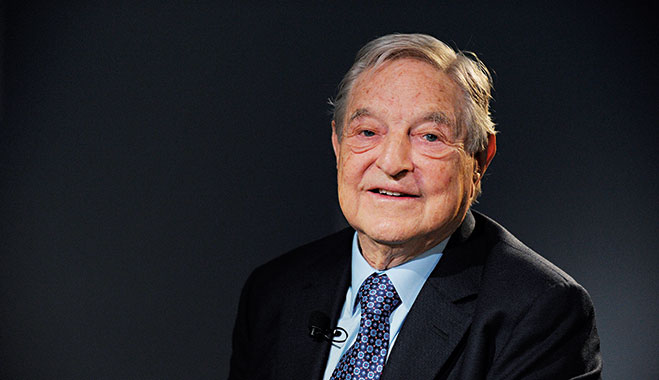

Following this news, Leigh-Pemberton contacted Schlesinger, who claimed that his comments had not been authorised. He went on to assure his British associates that the remarks would be clarified in a statement the following day. The problem, however, was that while European markets then closed for the night, across the Atlantic they were still very much in motion. News of the situation soon reached George Soros’ Quantum Fund in New York.

Playing the market

Business magnate and financial investor George Soros had only a month earlier started to build up a considerable short position in sterling. If the pound were to devalue, Soros would make an immense profit. By that afternoon, Quantum Fund’s chief portfolio manager had noticed the news of the German central banker’s fateful comment. As he informed Soros, the magnate saw his opportunity to move against the pound and make his short pay out. “Go for the jugular”, he told his portfolio manager.

The fund then initiated a massive sell-off of the pound and encouraged others to do the same. As European banks attempted to purchase the pound in order to prop up markets the next day – a day that was to become known as Black Wednesday – they saw few results. Two orders of £300m were put in before 8:30am on September 16, but to no effect: Soros’ fund was dumping pounds at a faster rate than the Bank of England could buy them.

“The financial markets generally are unpredictable… The idea that you can actually predict what’s going to happen contradicts my way of looking at the market” – George Soros

As The Times quoted Soros in the aftermath: “Our total position by Black Wednesday had to be worth almost $10bn. We planned to sell more than that. In fact, when Norman Lamont said just before the devaluation that he would borrow nearly $15bn to defend sterling, we were amused because that was about how much we wanted to sell.”

Attempts to raise the interest rate further proved fruitless, even with rates at one point reaching 12 percent, followed by a promise to raise them by a further three percentage points. By 7pm in the UK, Britain had been forced out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism, its currency devalued. Soros’ short position paid off, earning himself over $1bn and the title of ‘the man who broke the Bank of England’ with it.

Finding his fortune

Soros was not a man to be underestimated. After surviving occupation by the Nazis and then by the Soviets in his native Hungary, Soros moved to the US and built himself a financial empire and fortune through his genius as an investor, earning him a spot among the wealthiest men in the world.

Born in 1930 to parents Tivador and Elizabeth in Budapest, Hungary, Soros was originally known as George Schwartz. Tivador, a lawyer and World War One veteran, changed the family name to Soros in 1936, and taught his son the constructed international language Esperanto from an early age.

When George Soros was 13 years old, Hungary was occupied by Nazi Germany. The Jewish Soros family was in grave danger, and survived by going into hiding and using forged documents. The following year, in 1945, Soros also survived the viciously fought Battle for Budapest, which saw close-combat, house-to-house fighting between the Germans and the Soviets.

In 1947, Soros emigrated to London, leaving behind the then Soviet-occupied Hungary. Scraping by as a railway porter and waiter, he studied philosophy at the London School of Economics (LSE) under the esteemed philosopher Karl Popper. After graduating with a bachelors and PhD in philosophy from the LSE in 1954, the future hedge fund mogul found a job selling souvenirs wholesale to seaside shops on Welsh beaches. Not content with this career, Soros applied for jobs at a number of merchant banks, although with little luck, facing a number of rejections or ridiculing interviews. Eventually, however, Singer & Friedlander – a financial services firm based in London – decided to take him on. Soros joined the company as a clerk before moving to the arbitrage department.

Two years later, on the advice of a colleague, he applied for a position at the brokerage house FM Mayer of New York. Here he worked as an arbitrage trader, focusing on European stocks. In 1959 he started working as an analyst of European securities at Wertheim & Co., where he further developed his theory of reflexivity, something that he had first established while studying at the LSE. Building upon the thought of his former teacher, Popper, Soros’ theory aimed to explain the nature of market fluctuations. In 1963, Soros served as a vice president at Arnhold and S Bleichroeder, and it was here that he opened a number of funds, honing his investment strategy and theory of reflexivity.

After developing his method, Soros was able to start applying it in practice, beginning with a fund that he set up in 1966 with $100,000 of his employer’s money. In 1970 he set up his own firm, Soros Fund Management, which eventually grew to be one of the most successful hedge funds in the world.

With an aggressive trading style and a keen eye for short sell speculations, his fund quickly began seeing returns in excess of 30 percent per year, and twice posted annual returns of more than 100 percent. Although he gave up day-to-day hedge fund management in the 1980s, Soros still exerted considerable control over the organisation and continued to make huge profits by playing the market, eventually making him one of the richest men in the world. The US-Hungarian citizen is today estimated to have a net worth upwards of $24bn, and along with being counted among the 30 richest men and women in the world, he is known as the world’s richest hedge fund manager and one of the top 10 richest Americans.

With more free time and cash to spare, Soros was then able to branch out into another interest of his: politics and charity. As early as the 1970s, Soros had started to fund noble causes, including support for dissidents in communist eastern Europe in the 1970s and backing those opposing South Africa’s apartheid system.

In 1993, Soros founded the Open Societies Foundation, which has since dedicated millions of dollars to causes in the pursuit of democracy and liberalism. The organisation supports civil society groups around the world, hoping to promote justice, education, press freedom and public health. Among his most notable work has been the pursuit of the democratisation of his homeland, along with other eastern European nations that were suffering in the grasp of communism. He has also supported a number of other causes, such as advancing the rights of the Roma people in Europe and reforming US drug and immigration laws. The foundation reported a yearly expenditure of $827m in 2014.

Upon receiving an honorary degree from the University of Oxford, Soros was asked how he would like to be introduced during the ceremony. He replied: “I would like to be called a financial, philanthropic and philosophical speculator.”

George Soros in numbers

$24.2bn

Soros’ estimated net worth, 2015

29th

Soros’ position on Forbes’ 2015 ranking of the world’s billionaires

$10bn

The amount of sterling short sold by Soros’ firm on Black Wednesday

$11bn

Donations to various causes between 1979 and 2015

Men of business

The US is often noted, in comparison to Europe, for its lack of prominent public intellectuals – not for want of thinking men or women, intellectuals in the US have, for the most part, tended not to capture public imagination as they have in Europe. Rather, the country seems to look more to men who have proven themselves in the practical world of business and finance.

Acquiring a fortune in the world of business is more of a prerequisite to catching the eye of the American general public than writing an abstruse thesis at the École Polytechnique, or ruminating on the left bank of a certain river. However, the history of his overwhelming success has turned George Soros into someone that people listen to.

American capitalism and the opportunities it offers have produced many such public figures, but few as prominent as Soros. Along with his long list of philanthropic pursuits and advocacy for democratic causes around the world, Soros has positioned himself as a dispenser of economic and financial prophecy and analysis. His success in the industry has allowed him to take up the mantle of market guru. It’s hard not to at least consider the advice of a man who has the achievement of short selling one of the world’s largest economies attached to his name, as morally dubious as such an accomplishment may be.

The year 2015 had its fair share of financial crises and economy-centric headline stories: emerging markets saw their growth slow, and some, such as Brazil, entered crisis point. Oil prices continued to hit record lows. China saw its growth slow down, unbound volatility engulfed the world’s stock markets, and the eurozone stared down Greece, in what very nearly resulted in Greece’s withdrawal from the monetary union.

Less than a month into 2016, however, financial analysts were already predicting that the coming year would be even worse. Most notably, RBS and Société Générale both released ominous warnings of impending financial turmoil, while the Chancellor of the UK, George Osbourne, more soberly hinted at potentially troubling global economic conditions in the upcoming months.

Soros was another analyst to warn of troubled waters ahead: in early January, he announced that we were going to be facing 2008 all over again, as the current conditions in global markets were reminiscent of that fateful year. “China has a major adjustment problem”, Soros warned at an economic forum in Sri Lanka in January 2016. “I would say it amounts to a crisis. When I look at the financial markets, there is a serious challenge which reminds me of the crisis we had in 2008.” As a man who has made his fortune from shorting markets and making confident financial bets on global markets and the future of the world economy, his advice is perhaps worth heeding.