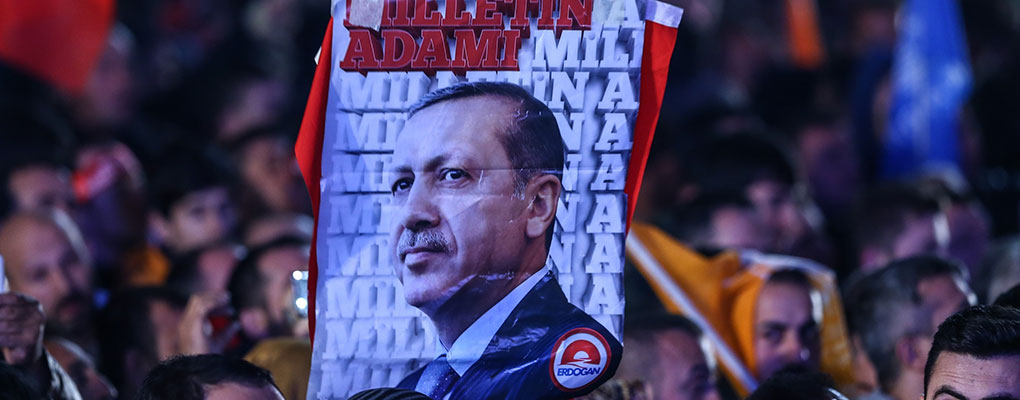

Following June’s bitter loss of parliamentary seats to the CHP, the Kurdish opposition party, ruling President Recep Tayyip Erdogan called for snap elections to take place just months later. The tactic was successful, and this time around, the Justice and Development party (AKP) can boast a sweeping victory with 49.4 percent of the vote. The result equates to 316 of the 550 parliamentary seats for the AKP, and thereby enables the return to a single party rule in Turkey.

The country is at a critical stage in its history and a point at which a new path will be paved

During a victory speech, Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, leader of the AKP, declared that the win outlined the decision by the public to choose stability and democracy for Turkey. The comments come in line with Erdogan’s persistent campaign message throughout the run up to elections, namely that the choice to be made by voters was between “me or chaos”.

As is evident by the fact that a second set of elections was called as the ruling party was dissatisfied by the result in June and the growing power of the Kurdish political voice, democracy has not in fact prevailed in Turkey. The snap elections themselves give further indication for Erdogan’s increasingly authoritarian approach and growing clampdown on opposition of any kind. In the past five months, the incumbent regime has also been criticised by the international community for raids carried out on media outlets that are known to be critical of the AKP, while various high profile journalists have also been imprisoned.

Using the growing tension among Turkey’s populace, as well as mounting concerns over violence with Kurdish militants and Islamist insurgents, Erdogan has manoeuvred the outcome of the election on November 1. While he, along with Davutoglu, maintains that stability will ensue, it is more likely that the result will exacerbate social discord instead. Turkey is a deeply divided country, with social cleavages along sectarian and ethnic lines that are gaining further prominence, particularly as the ruling government takes a turn towards greater conservatism. Arguably, a coalition party was indeed the best approach for peacefully governing a myriad of social sub-sects in Turkey, while also helping somewhat to curb Erdogan’s growing grip on power.

The AKP may have successfully relieved accusations of corruption in the past term, and may continue to do so in the future, yet the ruling party cannot hide behind economics. Economic success is the basis of Erdogan’s staunch support, and the reason why many of Turkey’s 53 million eligible voters continue to support him. Yet, as the once booming economy continues to slow, with the Turkish lira plunging by 25 percent in recent months, the realities of inequality and rising unemployment levels (which recently reached 11.3 percent) will soon permeate the national consciousness – among various groups at least.

The country is at a critical stage in its history and a point at which a new path will be paved. Unfortunately, the indicators point towards a Turkey that is turning its back on the liberal and modern philosophy of Kemal Ataturk, an unsettling thought for millions in the country. Erdogan’s last term illustrates that the incumbent regime is indeed heading towards a dictatorship, and with the tables now turning with Europe in terms of the balance of power, there is little to stand in the way of this final outcome – a real shame for the West’s once democratic bridge to the Middle East and the Turkish people.