When did capitalism become a dirty word? Despite what we are led to believe, it is not a political construct; it has absolutely nothing to do with politics. Adam Smith, the so-called ‘Father of Capitalist Thinking’ believed that free markets were not engines of extraction, but instruments of moral order, arguing that “humans were self-serving by nature but that as long as every individual were to seek the fulfilment of his or her own self-interest, the material needs of the whole society would be met.” In fact, he never even coined the term capitalism.

However, Smith’s simple explanation of markets has since been hijacked as we see business capital flow towards ‘engineering’ balance sheets rather than building factories, towards stock price rather than workers, and extraction instead of invention. This is more than a market distortion, it is an identity crisis, and with capitalism stripped of its moral core it risks becoming an economy of scraping value from value, rather than creating it.

Enterprise as moral progress

Smith didn’t see commerce as a cold machine, and believed, rightly or wrongly, that self-interest and sympathy could align to generate productivity and shared prosperity. In his ‘Theory of Moral Sentiments and Essays on Philosophical Subjects’ (1759), he argued that when individuals pursue their own gain within a moral framework, their labours often produce benefits beyond themselves, because we have in-built instincts that make us care about others’ well-being.

Buybacks only provide short-term stability. They mask any underlying issues

And this concept forms the basis of his ‘Invisible Hand Theory’ in his seminal work The Wealth of Nations about the unseen market forces that drive a free economy through self-interest and voluntary trades. The industrial revolutions that followed seemed to vindicate this ethos, and early capitalism wasn’t just about factories or markets, it was about harnessing innovation, trade, and employment to lift living standards and entire societies. Prosperity meant producing more, such as steel, textiles and railways, and the ‘real economy’ was capitalism’s moral anchor: enterprise equalled progress.

And for over 200 years, capitalism worked, on the whole, as Smith intended, with capital flowing into factories, infrastructure, and innovation, to create real wealth and shared prosperity. However, new financial tools, the rise of shareholder primacy, and a wave of financial deregulation in the 1980s redefined corporate priorities. Driven by financial investors who criticised managers for not focusing on shareholder interests during the economic challenges of the 1970s, this ‘shareholder value revolution’ shifted focus from building productive businesses and long-term growth to maximising short-term returns for shareholders, often at the expense of investment in workers, research, and tangible assets.

A pivotal moment in this transformation occurred in 1982 with the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s adoption of Rule 10b-18, which provided companies with a ‘safe harbour’ allowing them to buy back their own stock without risking accusations of market manipulation, provided they follow clear limits on timing, amount and price. Meanwhile the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 phased out interest rate ceilings on deposits and broadened the range of activities banks could engage in. In the UK, deregulation occurred through a series of legislative acts and market-driven changes, most notably the Big Bang in 1986, which freed London’s stock market by allowing foreign ownership of brokers, removing fixed commissions and automating price quotes.

Along with advancements in information technology, these developments facilitated the rise of financial markets and the prioritisation of shareholder value over traditional industrial growth, to fundamentally alter the landscape of capitalism.

The hollowing of enterprise

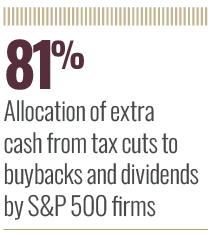

The use of stock buybacks has transformed from being a niche financial tool in the 1980s to a core mechanism for companies to return capital to shareholders. And while this can signal confidence in a company’s future, this diversion of funds from research and development (R&D), employee wages and business expansion has raised concerns about buybacks being used to boost earnings per share (EPS) and inflate stock prices. Unfortunately, this trend has been reinforced by executive pay, which often links CEO pay to short-term stock results. For example, in 2018, S&P 500 firms allocated a staggering 81 percent of extra cash from tax cuts to buybacks and dividends, but only 4.6 percent was spent on R&D.

In the technology sector, Apple announced a $110bn repurchase plan in 2024, while maintaining significant cash reserves, which raises questions about the allocation of resources between shareholder returns and investments in innovation. Similarly, Delta Air Lines repurchased $5bn of its stock in 2018, money, some would say, that would have been better spent on improving infrastructure or employee benefits. Even energy firms, despite record profits, have prioritised buybacks over investment in sustainable energy initiatives or projects that address environmental concerns. All of which illustrate the broader trend of financial engineering over investments to drive long-term growth and societal benefits.

Weakening markets and eroding society

For capitalism in the 21st century, this surge in stock buybacks has introduced a paradox. While companies may appear more profitable in the short term, the long-term health of both markets and society is increasingly at risk.

Wage growth has stagnated, which has only helped to widen the wealth gap

On the surface, by reducing share supply, potentially boosting EPS and making companies more attractive to investors, buybacks can stabilise stock prices. The 2021 US Chamber of Commerce report by Craig Lewis and Joshua White, ‘Corporate Liquidity Provision and Share Repurchase Programmes,’ which studied a large sample of more than 10,000 US companies over 17 years found six key benefits associated with buybacks: greater liquidity, reduced volatility, economic benefit for retail investors, proactive repurchase activity to stabilise stock price, responding to uncertainty by strengthening buyback activities, and using stock buyback as a strategic liquidity supplier.

But buybacks only provide short-term stability. They mask any underlying issues. With buybacks, companies risk diminishing their long-term competitiveness, as they divert capital investment away from R&D, infrastructure and workforce investment. This can lead to a decline in productivity and increased vulnerability during economic downturns, as firms may lack the necessary investments to adapt and innovate.

The societal impact is equally concerning. Prioritising shareholder returns over capital investment means that for many workers wage growth has stagnated, which has only helped to widen the wealth gap. And with companies allocating more funds to buybacks rather than paying income tax, according to a report by Americans for Tax Fairness, it raises questions as to their true commitment to societal welfare. As profits flow towards mostly shareholders and executives, workers are left behind, eroding trust in companies and challenging capitalism’s fairness and moral legitimacy.

Rethinking capitalism in 2025

As we move into the second quarter of the 21st century, capitalism, or rather what it has morphed into, is in desperate need of a makeover. But with the whole world seemingly in a financial mess, how can we realign economic incentives with long-term societal well-being?

In terms of policy reforms, one suggestion is to restrict excessive stock buybacks either through increasing the tax on repurchases or treating buybacks similarly to dividends and taxing accordingly. One other crucial measure to implement is realigning executive pay from short-term results to long-term performance.

However, policy tweaks alone won’t restore faith in capitalism. There is a growing push to rethink how companies invest, grow, and define success through a combination of stakeholder capitalism and patient capital. Valuing workers, customers, and communities, instead of shareholder returns, and investing money for the long term rather than a quick win, will, invariably, give businesses room to innovate and grow. Additionally, by implementing green industrial policies, governments can steer investment into clean energy, new technologies, and infrastructure to speed the shift towards a low-carbon economy.

Rediscovering capitalism’s moral core

Was Adam Smith right? Is self-interest only justifiable when it serves society? If recent social commentary is anything to go by, economic systems without this alignment risk inefficiency and moral erosion. And, like Mr Darcy’s good opinion, trust in the system, once lost, is hard to get back, while markets based purely on extraction instead of creation are unstable.

Capitalism with a moral core provides more than ethical reassurance; it encourages people to act responsibly and predictably, creating stability in how businesses and markets operate. And companies that embed social purpose into strategy often foster loyalty, spark innovation, and encourage responsible risk-taking, with studies showing that those committed to ESG often outperform others, proving that profit and purpose can coexist.

Building businesses and creating wealth is not, as social media would have you believe, inherently evil. But without an ethical anchor, rewarding short-term gain at the expense of collective welfare is what has given capitalism its bad name.

With that moral anchor, people can see economic success as serving society, and it is a win-win all round; companies become stronger and more resilient, communities trust those companies to reinvest, workers feel valued, and investors gain confidence that profits are sustainable in the long term.