As climate change and the green transition gather momentum in 2025, unlikely commodities such as copper and cocoa are now reshaping global economic stability the way oil once did. Copper prices have surged more than 20 percent so far this year, driven by supply crunches, green infrastructure and data centre demand. Similarly, cocoa has seen extreme price volatility, due to African climate shocks, hitting record highs in early 2025, before plummeting almost 50 percent.

Together, they highlight a broader geopolitical shift away from fossil fuels towards essential commodities and natural resources. With copper driving the energy transition and cocoa shaping food supply chains and ethical trade, they have become the dual bellwethers of a changing world order.

They also represent how resource power and strategic assets are increasingly concentrated in the Global South, in West Africa’s cocoa heartlands and Latin America’s copper belt. In many ways, copper and cocoa are now the ‘new oil’ – strategic, scarce and representative of both innovation and global inequality.

Underpinning the climate transition

Copper is essential to electrification, being used in electric vehicles, solar panels, wind turbines, hydropower plants, grid upgrades and more. Demand for copper from data centres, where it is used in cooling systems, internal connectivity and power systems, has increased exponentially, supported by the surge in artificial intelligence.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), copper demand could hit 31.3 million tonnes by 2030, a considerable increase from 2021’s approximately 24.9 million tonnes. “China’s massive grid expansion and urban development have been the single largest recent driver of copper demand. Continued Chinese industrial stimulus and infrastructure spending are therefore key factors underpinning copper prices,” António Alvarenga, Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at Nova School of Business and Economics, explained. He added: “However, copper mine output has grown only about one to two percent annually, despite rising demand, and new projects take around 15–17 years to develop.”

Copper production is highly concentrated in Zambia and Democratic Republic of Congo, along with Latin America’s copper belt, including Chile and Peru. “This concentration of resources is quietly reshaping global alliances, as countries compete to secure long-term access, much like the oil geopolitics of the 20th century,” Sunil Kansal, head of Consulting and Valuation Services at Shasat Consulting, said.

Copper and cocoa mark a shift to the commodities of the future, scarce and economically resilient

As such, any mine accidents in these key countries can have a profound impact on copper production and drive prices up. Chile’s El Teniente mine had a deadly accident back in July this year, which led to a major production halt and drop in output. This was also seen at the Komoa-Kakula copper mine in DRC in April due to a flooding event and roof collapse. Older mines and chronic underinvestment have boosted copper prices and caused supply chain bottlenecks too lately.

“Many of the world’s major copper mines are aging, and the average copper content (ore grade) is declining, meaning that more rock must be processed to extract the same amount of copper,” Franck Bekaert, senior emerging markets analyst at Gimme Credit, highlighted. “Additionally, permit delays and ecological constraints are hindering the launch of new projects, which is driving up costs. To meet the growing demand for copper, significant investments will be required,” Bekaert added.

Political instability in major producing countries, such as worker strikes and environmental protests, as well as governance issues such as rising corruption have also contributed to supply woes. At present, copper inventories are at record lows, according to Benchmark Intelligence, even as green infrastructure demand from the US and EU soars.

As the world races to electrify, copper’s scarcity is fast becoming a structural risk to global growth, much like oil shocks once were.

How climate shocks impact cocoa

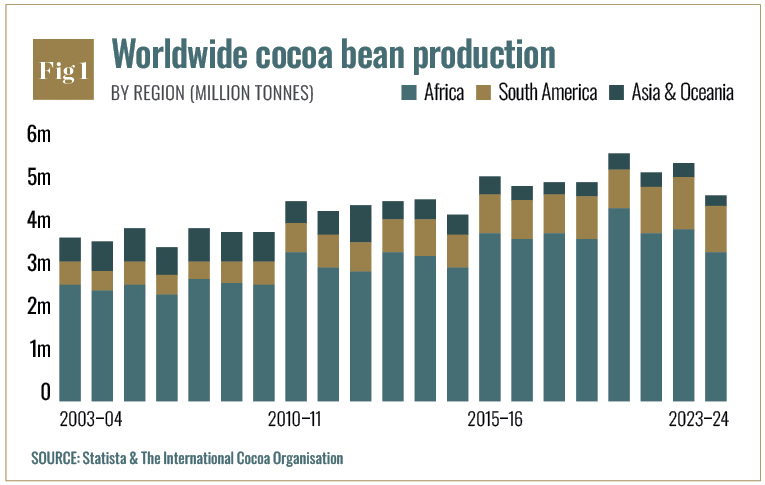

“When the Ivory Coast and Ghana sneeze, global chocolate catches a cold. Cocoa just had its ‘oil moment’: a near 500,000-ton global deficit in 2023–24 pushed inventories to multi-decade lows and sent futures above $10,000/ton at the peak in January 2025,” Francisco Martin-Rayo, co-founder and CEO at Helios AI, said. One of the biggest reasons for this was the El Niño weather pattern in the 2023–24 season. This caused volatile weather patterns, such as unusually heavy rain, followed by hotter and drier weather across key cocoa-producing countries such as Ghana and the Ivory Coast. Cocoa is very sensitive to weather changes as it grows only in limited areas of warm, humid equatorial conditions, with 70 percent of the crop coming from West Africa (see Fig 1). These temperature extremes caused decreased cocoa yields and a rise in crop diseases such as swollen shoot virus and brown rot. The diseases also meant that the remaining yield was of lower quality, further escalating prices. Aging West African cocoa trees are another factor contributing to higher prices. These can severely dampen yield capacity because of decreased soil fertility. Older trees can also be more vulnerable to diseases and pests and become weaker with time.

Farmers then need to invest large amounts in replanting and farm rehabilitation. However, consistently low farmer incomes make such investments difficult to maintain, creating a vicious cycle of aging trees, low productivity and low incomes.

“Cocoa demand has grown steadily. Western holiday consumption and an expanding middle class in Asia/Africa support baseline demand. However, extremely high prices can dampen consumption: in 2025 European and Asian cocoa grindings fell as manufacturers faced higher costs,” Alvarenga said. The factors affecting cocoa go beyond just determining chocolate and related product prices – they represent a systemic crisis in agricultural supply chains today, defined by climate volatility, worsening soil degradation and widespread farmer poverty. With much of the crop still tied to smallholder farmers, cocoa is a social commodity, intimately linked to human issues such as food insecurity, forced migration and income loss and inequality, sitting at the heart of debates about ethical sourcing and fair trade. Even as prices pull back slightly now, the structural issues driving cocoa price volatility remain.

Strategic assets

Much like oil in past decades, both copper and cocoa supply has been highly concentrated in a few regions. This has significantly shaped new geopolitical alignments and trade tensions. One of the biggest ways this has materialised is through consumers now actively seeking to diversify suppliers, to reduce supply chain and security risks. Copper, as a strategic metal and asset, is now crucial to countries’ decarbonisation plans. As AI and other cutting-edge technologies gather pace and require more electricity, copper’s status as the ‘new oil’ is likely to keep growing. As such, major copper consumers including the US and EU are now trying to find more suppliers to spread supply risks.

“The US launched a section 232 national security investigation into copper and China has pivoted away from Chile by sourcing more from DRC, Russia and Zambia. These moves have created new alignments – such as China deepening ties with African producers, Western nations seeking alternative mines or stockpiles,” Alvarenga highlighted. This geopolitical strategising and positioning mimics past resource wars over oil, creating new alliances between industrial powers and resource-rich countries. “As with oil, these relationships can lead to trade frictions, resource nationalism, and competition for influence. For investors, this concentration magnifies geopolitical risk but also signals long-term strategic value,” Edward Nikulin, weather model expert at Mind Money, said.

For cocoa, Ghana and Ivory Coast’s governments wield considerable supply influence through export regulations and price-setting, acting as a kind of producer bloc, similar to OPEC. “We are seeing the emergence of coordinated action by Ghana and the Ivory Coast to demand fairer terms, echoing the resource diplomacy once seen in oil markets,” Kansal said. This is through the ‘Living Income Differential,’ which raises export prices to ensure that more cocoa income reaches farmers directly to improve living standards and reduce child labour, poverty and deforestation.

“The joint $400/ton ‘Living Income Differential’ set a de-facto floor under farmgate economics, while EU deforestation rules (EUDR) are forcing farm-level traceability (GPS coordinates, plot IDs) and reshaping trade flows toward compliant suppliers,” Martin-Rayo explained. “Expect more local processing in Abidjan and San-Pédro and more origin diversification to Ecuador/Brazil a classic resource-security realignment.”

Cocoa farming is increasingly using more tech such as satellite imagery, robotic pollination, ground sensors and drones. These monitor pests, growth rates and soil moisture in large plantations in real time, helping yields to become more stable, which can boost cocoa’s economic and strategic importance. Similarly, more major copper companies are focusing on responsible copper production practices, addressing sustainability and labour concerns that are key to attracting the next generation of investors. “Over the past five years, copper and copper miners have significantly outpaced the S&P 500 and broad commodity indices. Dedicated copper ETFs and mining stocks have been popular. Upside for investors comes from expected supply deficits: pent-up demand from EVs/renewables could lift prices if new mine output lags,” Alvarenga said.

However, he emphasised that policy intervention risks like stockpiling and tariffs remain, which could suddenly decrease copper flows. Although cocoa is more volatile and speculative than copper, Martin-Rayo calls its oil-like status a regime shift. “Think of cocoa as smaller than oil, but newly ‘systemic’ for food manufacturers and retailers.”

The road ahead

2025 highlights the start of a ‘post-oil’ resource era – one where sustainable and ethical commodities hold power. The ‘new oil’ may be mined, grown or digitally verifiable, instead of liquid. Both copper and cocoa mark a shift to the commodities of the future, scarce and economically resilient in an increasingly fragmented world, with investors demanding balance between transparency, accountability and growth.