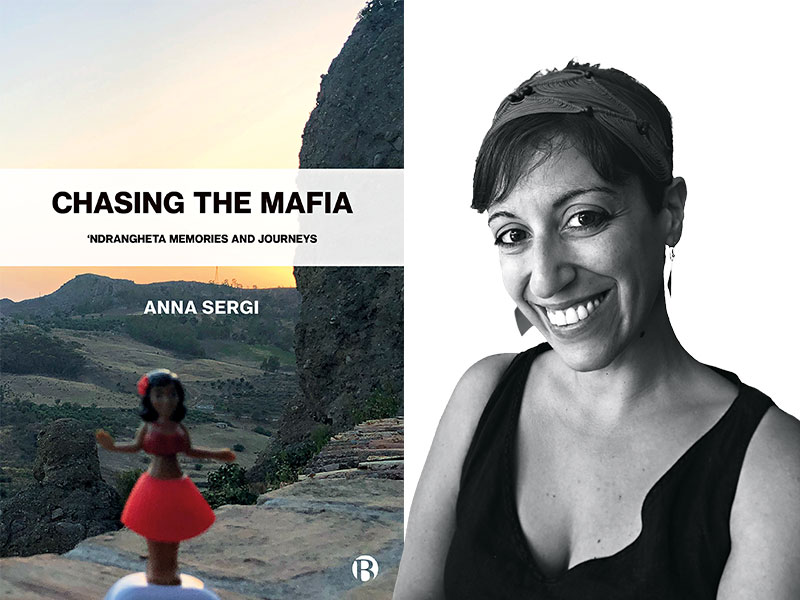

Hailing from Aspromonte, a mountainous region in Southern Italy, Anna Sergi has first-hand experience of the mafia’s devilish appeal. Her latest book Chasing the Mafia is an idiosyncratic travelogue that combines memoir, sociological analysis and investigative journalism. Through anecdotes, personal memories and records of criminal cases, the University of Essex criminologist dissects the inner workings of the most powerful of Italian mafias, the Calabrian ‘ndrangheta, explaining how it spread its tentacles around the world, often with the complicity of banks. From the pristine beaches of Australia to Canada’s snow-covered prairies, Sergi follows the traces of a versatile organisation that is decentralised, globalised and innovative, just like a modern business. Beating it, she explained to World Finance’s Alex Katsomitros, will take a bit more than heavy-handed policing and money thrown at the problem.

What is the ‘ndrangheta?

It started as a brotherhood of so-called ‘honourable men’ that appeared after Italian unification in 1861. Fast forward 100 years and you find an organisation well established in the small villages and cities of southern Calabria, a region suffering from the perception that southern Italy is different. During the ‘Mafia Wars’ in the 1960s and 1970s, the clans needed money, because Calabria was poor. Younger generations started the so-called ‘kidnapping season,’ kidnapping around 160–200 people until the government made it legally difficult to pay ransom. They made a lot of money that was later reinvested, notably in cocaine.

How did they overtake Cosa Nostra?

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Sicilian Cosa Nostra was involved in a bloody war, won by the Corleonesi clan. They were headed by Toto Riina, a psychopath. Sicily was in a state of war, with killings in broad daylight. This was the peak of Cosa Nostra’s power, but also its demise. In 1992, it decided to attack the state, killing judges Falcone and Borsellino and planting bombs in northern Italy. The same year the port of Gioia Tauro was opened where the ‘ndrangheta invested money from kidnappings, moving into the profitable drug trade. The Italian state was going through its own crisis. A corruption scandal erupted that shook the political system. So the state was weak and its few resources were focused on Sicily. Calabria remained in the shadows until 2008 when we had the first ‘ndrangheta report. By then, it had dominated the cocaine trade.

Did its decentralised nature contribute to its success?

Absolutely. Cosa Nostra failed because it centralised everything in the hands of a psychopath. It has a top-down structure where the boss-of-bosses decides everything. The ‘ndrangheta is the opposite. Clans are autonomous. They don’t have to agree on a strategy – that happens only on a need-to-know basis. Coordination structures are not hierarchical, they are about recognising who has more power. Those who do, sometimes come together to solve problems.

Everyone is laundering money through the City, not just Russians.

How do they launder money?

It’s rarely laundered in Calabria, because the authorities are well-versed in discovering that activity. Laundering usually happens in northern Italy or Europe. ‘ndrangheta clans invest in small, cash-intensive businesses like restaurants. Sometimes you see bigger investments through puppet intermediaries that participate in consortia bidding for EU funds.

Is there collusion with banks?

Usually the ‘ndrangheta launders drug money through third-party brokers, other criminal groups that operate as intermediaries: Chinese for Europe and Pakistani or Indonesian for Australia. The second layer of money laundering involves direct engagement with banks; in Europe, Switzerland, the UK, Belgium and any country that allows ‘smurfing’: holding small sums in individual accounts without asking many questions. So European banks are complicit.

When the war in Ukraine started, the City was criticised for laundering Russian money. Is the ‘Italian connection’ big too?

Everyone is laundering money through the City, not just Russians. Why wouldn’t they? It’s easy. There are two types of UK-based financial intermediaries. Individual brokers, usually Italian, who make fake investments or launder money through the legitimate financial system. Alternatively, you have investment in shops or real estate. In one recent case, a clan was laundering money by selling non-existent flats in Calabria to British clients through a London law firm. Usually these deals get discovered when brokers get in trouble for something else.

Have they also started offering their own banking services?

Some clans do, especially clans from the city of Reggio Calabria where they are particularly financially savvy. There is a shift from drugs to more sophisticated activities like banking fraud. They provide fake financial services as loan sharks.

Does the ‘ndrangheta tap into the increasing complexity of the financial system to hide money through its army of financiers, lawyers and accountants?

Absolutely. They have these types of professionals within clans. It’s unbelievable how many lawyers some families have. They have fewer accountants, but sometimes some financial services and tax advisors. They also bribe people, but that’s riskier.

Do governments condone this sort of financial crime?

You can’t control every single transaction. You either have financial efficiency or complete safety. There is a utopia of safety whereby we assume that everything is safe. But in reality there is a threshold of tolerability where certain things are allowed until they become too problematic. In Australia, Italy and Germany, things are getting problematic, because they are expanding into other activities, like manipulation of elections. There is cocaine, but also investment in the legal economy. So what’s the priority? Is it to stop dirty money from entering the financial system? Or catch it after a company has been set up? Usually it’s the second.

Raymond Baker, an authority on financial crime, recently told World Finance that US authorities should try to stop drug money laundering, rather than just trafficking. Would that work with the ‘ndrangheta?

The point of drug trafficking is to make cash. Mafiosi don’t want to live an illegal life. They launder money in ways that evolve into semi-legal activities. Some clans don’t even want to be mafia groups forever. So it should be a priority. But you can’t even stop half of large-scale money laundering. Banks don’t want to do more checks, their clients wouldn’t like it. Do we want more efficient or safer finance? Efficiency always wins.

You mention in the book that the Mafia delegitimises the state’s authority. Does it tap into localism, especially Southern Italian separatism?

Italian mafias have exploited separatist movements, particularly a sentiment that order can only derive from local rather than national authority. But there is no ideology, no will to substitute the state or create an alternative one. They just take advantage of its weaknesses. For Calabrians, the state has many, many faces. It’s not always reliable. Its anti-mafia procedures are often contradictory. The mafia exploits this ambivalence to convince people that they should trust them rather than the state.

So what can governments do? Is economic development the solution?

Economic development alone won’t solve the problem. Mafias are parasites, the more you give them to steal, the more they will steal. What you can do is create economic wealth that translates into social wealth. One problem the mafia faces is recruitment. It’s a matter of alternatives for people. Some NGOs provide alternative paths and that’s disrupting for mafia families. However, employment and education are poor in Calabria. People distrust the government and try to find shortcuts. When those shortcuts become organised, you have mafias. Italy will receive EU funds for post-Covid recovery that could go into ‘levelling up,’ but until we level up education and employment expectations, not much will change. You can’t just send money there and hope that it will solve the problem.

Is the current Italian government doing enough to tackle the problem?

No. Meloni leads a populist far-right movement that is very anti-South. Everything she’s proposing is undermining anti-mafia investigations. They are passing legislation that limits the types of surveillance and financial investigations prosecutors can do. She supports those who believe that there is something wrong with the South, alienating people. Her government makes the mistake that many other politicians made: considering the mafia a cancer that needs to be extirpated, instead of understanding its roots within society. No Italian government has done anything serious against the mafia for at least 15 years.

Will the digitalisation of the economy weaken the ‘ndrangheta?

As Falcone said, the mafia is a human phenomenon that has a beginning and an end. We just don’t know when that end is. Mafias adjust to economic changes. Currently within the ‘ndrangheta there is a tendency to evolve into semi-legal service providers. Today, most ‘ndrangheta families are indistinguishable from other family businesses. What distinguishes organised crime is that it’s not just about profit. It’s about power, control of territory. If you weaken their power, their profit-making capacity will suffer. But I don’t think I will see that in my lifetime.

You are from Calabria. Have you ever felt threatened because of your job?

I have never felt threatened. I have felt being observed, but I know the difference between being observed because of curiosity and as a threat, because my father, a journalist, had received threats. I have felt intimidated in Australia. If you are embedded in the territory, your family is there and you are perceived as a troublemaker, then intimidation will be about people around you and coming from people around you. I don’t think I create problems because I talk about the mafia. They are used to that. I might be perceived as a troublemaker abroad, because I raise public awareness, for example by participating as an expert witness in trials in Australia or Germany. As a Calabrian, I recognise intimidation. But I hope they are too smart to target me.