Since the 1980s, labour’s share of national income in advanced economies has gradually been whittled away by technology and globalisation, according to a report published by the IMF on April 10.

Just prior to the onset of the 2008 financial crisis, the share of national income received by workers dipped to its lowest level for the past half century, and has since made no material recovery.

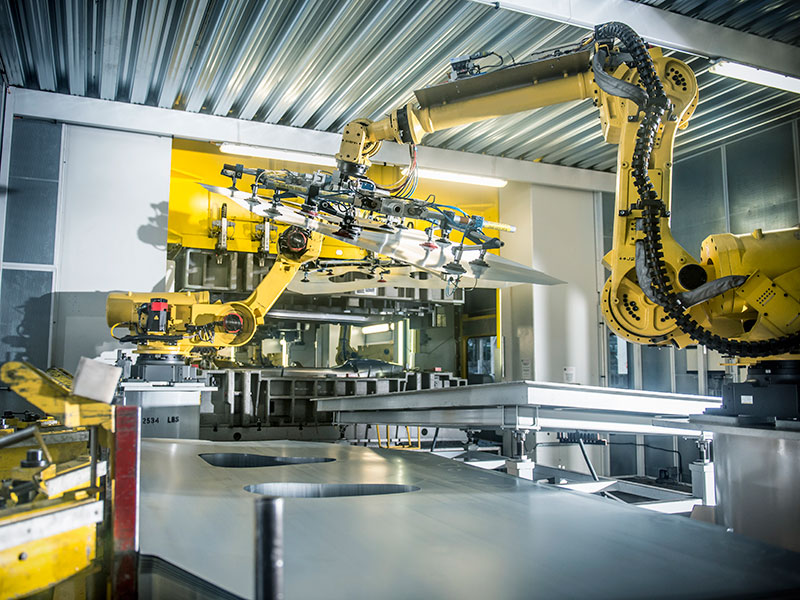

The hit to workers was attributed to a high share of jobs becoming automated, as well as the rapid progress in information and telecommunications tech

The IMF report, titled Understanding the Downward Trend in Labour Income Shares, identified technology as the primary cause of labour’s shrinking share of income for advanced economies. “In advanced economies, about half of the decline in labour shares can be traced to the impact of technology”, reads an IMF blog post based on the report.

The hit to workers was attributed to a high share of jobs that could be automated, as well as the rapid progress in information and telecommunications tech. Technology can also be harmful due to the implications for “job polarisation”, according to the report, whereby middle-skilled labour was under greater threat from routine-biased technology. This then sharpens the disparity in wages between different skill levels.

Global integration was also found to play an important role, but its impact was judged to be around half as important as that of technology.

The labour share of income measures the proportion of national income paid in wages to workers, rather than capital incomes. While it is not necessarily a direct measure of unemployment, a fall in the labour share of income will usually occur in parallel with an increase in inequality. This is in part because those who own capital tend to already be clustered around the top of the income distribution.

The report provides support to arguments being pushed by the big global institutions, which are speaking up increasingly against the tide of trade protectionism.

On the same day, the IMF released a second report – published in partnership with the World Bank and World Trade Organisation – which argued that with the right policies, it is possible to embrace the opportunities that trade brings, while lifting up those who have been left behind. It stated: “Adjustment to trade can bring a human and economic downside that is frequently concentrated, sometimes harsh, and has too often become prolonged. It need not be that way.”