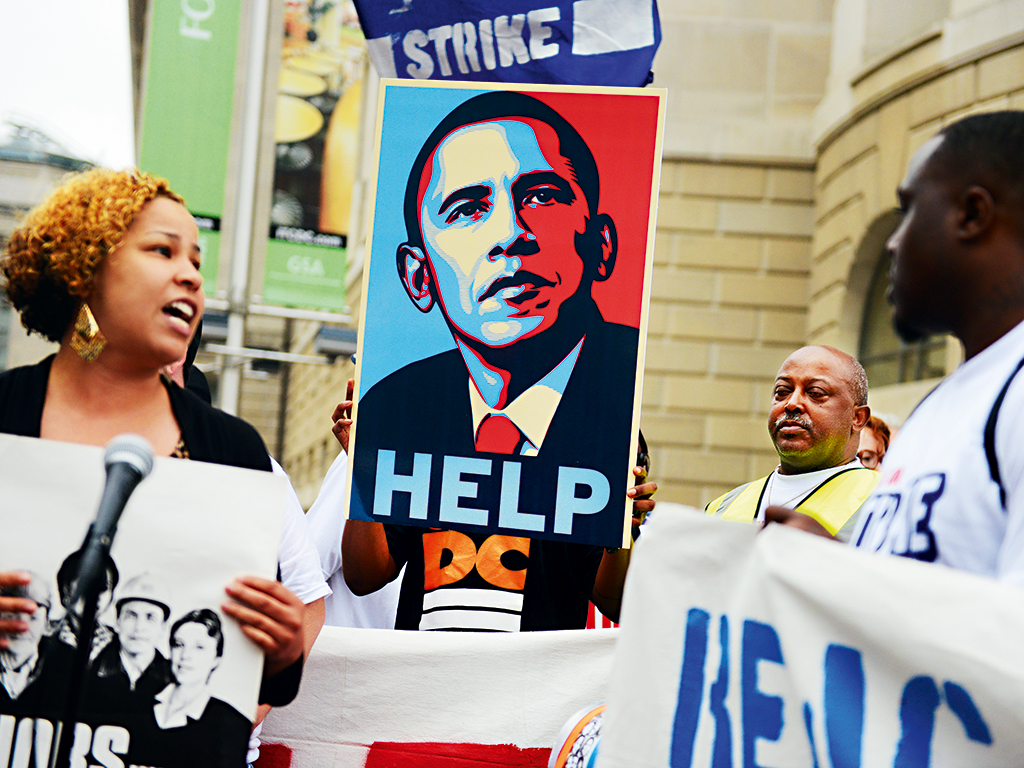

‘Workers need a McLiving Wage – not lovin’ it,’ read a printout placard late on last year, as hundreds of America’s $7.25 per hour earners grouped outside their respective retail outlets and fast food chains, buoyed by the President’s stated intent to bump up the federal minimum to as much as $10.10.

Talk of the minimum wage and how raising it could well lift millions out of poverty has gathered momentum for some time now (see Fig. 1), with many keen to make clear their thoughts on the matter and the various ways in which the world’s largest economy could benefit as a result. The issue is one that has most certainly divided opinion between Liberals and Conservatives, with both sides equipped with reams of research to back up their respective claims.

Proponents claim a wage hike would lift millions of Americans out of poverty and close the widening income inequality gap; a sentiment that is echoed by those receiving the sum, who represent 2.8 percent of the nation’s workforce. “Evidence suggests that raising the federal minimum wage from its current level would not destroy many if any jobs and would benefit low-paid workers who are struggling to maintain their living standards,” says Alan Manning, Professor of labour economics at the London School of Economics.

“The rise in wage costs are, to some extent, offset by a likely fall in turnover and absenteeism costs as work becomes more attractive.” However, critics argue that raising the minimum wage could well prompt employers to cut staff numbers, increase costs and illegally skirt additional expenses. “It’s difficult to see how forcing businesses to increase their labour costs would be good for them,” says Jonathan Meer, economist and research fellow for the National Bureau of Economic Research. “There’s no free lunch: someone has to pay the increase in labour costs.”

Costs of doing business

“Tonight, let’s declare that in the wealthiest nation on Earth, no one who works full-time should have to live in poverty, and raise the federal minimum wage to $9 an hour,” said President Obama last year in the State of the Union Address.

While it’s easy to theorise about how a raise could well afford unskilled workers a better standard of living, this school of thought is but to ignore the consequences for business. “Any government action that jacks up costs is negative for business,” says Bill Poole, senior fellow at the Cato Institute, Senior Advisor to Merk Investments and, as of fall 2008, Distinguished Scholar in Residence at the University of Delaware. “Businesses that employ a lot of minimum wage labour will be disadvantaged relative to other businesses.”

Critics argue that doing away with this advantage could have wider consequences for labour markets, as was very much the case in the early 1900s, when the US minimum wage was first introduced and rendered certain candidates unemployable, destroying both jobs and businesses in the process.

Even so, proposals to raise the minimum wage have received support not just from low-paid employees but also from small business owners themselves, according to a survey of 600 published by Wells Fargo and Gallup. The results show that 47 percent of respondents are backing the raise; despite 60 percent claiming the hike would hinder the majority of small businesses, which only serves to illustrate the complexity of the issue at hand here.

The implications of a raise, far from confined to employees, extend to employers, as those without the finances to accommodate change are likely to fall by the wayside, these being smaller businesses that are unable to compete on quite the same scale as larger more established firms.

In the near term, firms employing a lot of low-paid workers could pass on prices to consumers, reduce employment opportunities or take a profit hit, whereas long-term they might outsource work or mechanise labour intensive processes. “Everything depends on the level at which the minimum is set – if it is set too high it will destroy jobs as well as profits,” says Manning, who emphasises above all that the repercussions are dependent on the amount by which the minimum is raised.

“During an adjustment period, profits may well suffer. Some marginal firms will have to close, such as fast-food restaurants in poor locations. It is also worth noting that many non-profit businesses hire minimum wage labour. For example, some inner-city day care centres may be forced to close because the families they serve cannot or will not afford the higher fees,” says Poole. While fierce proponents of the hike may argue that those affected largely equate to economic deadwood, the importance of small businesses as an economic driver should not be underestimated in the current climate.

Another likely consequence of the rise is that those illegally undercutting the federal minimum could benefit from the hike, while those abiding by the legal amount will be forced to concede higher costs and cut staff numbers. “Businesses paying the minimum may be undermined by competition,” says Len Shackleton, Professor of Economics at Buckingham University and author of Should We Mind the Gap?

“Another more serious problem arises if legitimate minimum-paying businesses are undermined by competition from the ‘shadow economy’ where employers avoid taxes and the minimum wage. In most countries construction and house repair are areas where this happens to a degree.”

Who works for minimum wage anyway?

With US labour markets in the fragile state they are right now, the country can ill afford to stymie the prospects of a population still reeling from financial crisis. “Right now about 20 percent of young workers are unemployed, as are about 10 percent of the least-skilled adult workers. Raising the minimum wage raises the cost of hiring these workers, and it seems to me that in a labour market as weak as ours that is an unwise thing to do,” said Michael Pratt, economist and resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

Granted, the arguments on both sides are underpinned by sound economic theory, however the real world consequences are highly uncertain no the matter the decision. While discussions of minimum wage are so often accompanied by talk of income equality, there is evidence to suggest that those on the rate are far from those worst affected by poverty. “I don’t regard the minimum wage as an effective anti-poverty device as most of the people it benefits are not in poverty,” says Shackleton.

[C]ritics argue that raising the minimum wage could well prompt employers to cut staff numbers, increase costs and illegally skirt additional expenses

“Many are students and young labour market entrants who need experience if they are to progress. To the extent that it reduces demand for labour, with fewer jobs and/or less hours offered, these groups lose out. There is some evidence that minorities in particular lose out.”

Heritage Foundation calculations gathered from the US Census Bureau data reveal that just over half of the country’s minimum wage earners fall between the ages of 16 and 24, and that most are not under threat of falling below the poverty line whatsoever. Of the 16-24 sample, 79 percent worked part-time jobs and 62 percent were enrolled in school during non-summer months.

For this reason, further consideration should be paid to who exactly would be affected by the rise, and whether reeling a select few out of poverty is worth the potential consequences of raising unemployment and reducing the ease of doing business. “The effect on employment is unambiguously negative,” says Poole. “How large the effect will be depends on how large the increase in the minimum is,” with the scholar here making reference to an opinion held by some, claiming a small hike in wages would have little to no impact on unemployment.

For instance, the efficiency wage hypothesis theorises that employee productivity will gain alongside wages, as higher pay somewhat reduces the chances of unionisation and increases efficiency.

Many remain unconvinced by this textbook style of economics, however, Poole among them, who argues, “Why would the effect of a small increase be literally zero when the effect of a $50 minimum would obviously be large? Large increase, large effect; small increase, small effect, it’s Just that simple.”

Ultimately, the consequences of a raise will align with the extent by which the minimum is changed – if at all. Having said this, regardless of whether the affects are nominal or not, it’s important that a more thorough understanding is ascertained as to the actual repercussions, before the federal minimum is changed at the expense of American business and unemployment